The Tennessee State Capitol, located in Nashville, Tennessee, is the seat of government for the U.S. state of Tennessee. It serves as the home of both houses of the Tennessee General Assembly–the Tennessee House of Representatives and the Tennessee Senate–and also contains the governor's office. Designed by architect William Strickland (1788–1854) of Philadelphia and Nashville, it was built between 1845 and 1859 and is one of Nashville's most prominent examples of Greek Revival architecture. The building, one of 12 state capitols that does not have a dome, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 and named a National Historic Landmark in 1971. The tomb of James K. Polk, the 11th president of the United States, is on the capitol grounds.

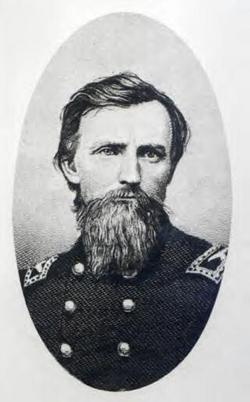

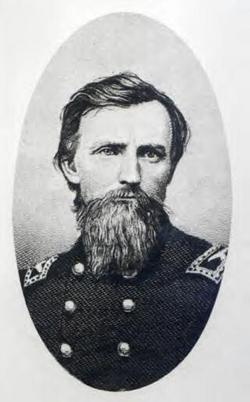

Hans Christian Heg was a Norwegian American abolitionist, journalist, anti-slavery activist, politician and soldier, best known for leading the Scandinavian 15th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment on the Union side in the American Civil War. He died of the wounds he received at the Battle of Chickamauga.

Christopher Columbus is a bronze statue of Italian explorer and navigator Christopher Columbus. It was installed during 1933 in Chicago's Grant Park, in the U.S. state of Illinois. Created by the Milanese-born sculptor Carlo Brioschi, it was set on an exedra and pedestal designed with the help of architect Clarence H. Johnston. It was removed and put in storage in 2020.

Forward is an 1893 bronze statue by American sculptor Jean Pond Miner Coburn depicting an embodiment of Wisconsin's "Forward" motto. The 1996 replica is located at the Wisconsin State Capitol grounds at the top of State Street. The statue often is misidentified with the Wisconsin statue on top of the Capitol dome.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, opening the way for European exploration and colonization of the Americas. His expeditions, sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, were the first European contact with the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. He has been represented in many fictional and semi-fictional works, including plays, operas, films and TV, as well as literary works.

Christopher Columbus, also known as the Christopher Columbus Discovery Monument, is a c. 1890–1892 copper sculpture depicting Christopher Columbus by Alfonso Pelzer, installed on the Ohio Statehouse grounds, in Columbus, Ohio, United States.

The Monument to Christopher Columbus is a statue by French sculptor Charles Cordier first dedicated in 1877. It was originally located on a major traffic roundabout along Mexico City's Paseo de la Reforma, and was removed on 10 October 2020 in advance of protests.

Richmond, Virginia, experienced a series of riots in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. Richmond was the first city in the Southeastern United States to see rioting following Floyd's murder. Richmond, formerly the capital of the short-lived Confederate States of America, saw much arson and vandalism to monuments connected with that polity, particularly along Monument Avenue.

A statue of Edward W. Carmack was installed in Nashville, Tennessee, United States in 1924. The statue was the work of American sculptor Nancy Cox-McCormack. Carmack was an opponent of Ida B. Wells and encouraged retaliation for her support of the civil rights movement.

A statue of Christopher Columbus was installed in Richmond, Virginia in 1927, where it stood until 2020 when it was torn down by protestors in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and thrown into a nearby lake.

A statue of Christopher Columbus was installed in Pioneer Park, San Francisco, California.

The equestrian statue of John Brown Gordon is a monument on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The monument, an equestrian statue, honors John Brown Gordon, a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War who later become a politician in post-Reconstruction era Georgia. Designed by Solon Borglum, the statue was dedicated in 1907 to large fanfare. The statue has recently become a figure of controversy over Gordon's racist views and associations with the Confederacy, with some calling for its removal.

The Middletown, Connecticut Christopher Columbus statue was a memorial to Columbus that was installed in the city's Harbor Park. The sculpture was donated to the city in 1996 by the Italian American Civic Order, the Italian Society of Middletown and local Italian-American families.

A statue of Christopher Columbus was installed in Columbia, South Carolina, United States as part of the Columbus Quincentenary. The memorial was removed and placed into storage in June 2020.

A statue of Christopher Columbus was a memorial in Washington Park in Newark, New Jersey, within the James Street Commons Historic District. It was made in Rome by Giuseppe Ciochetti and presented to the city by Newark's Italians in 1927. The statue was removed by the city in June 2020 to prevent its toppling in a Black Lives Matter protest.

The Christopher Columbus Monument was a marble statue of the explorer Christopher Columbus in the Little Italy neighborhood of Downtown Baltimore, Maryland. The monument was brought down by protesters and dumped into the Inner Harbor on July 4, 2020, one of numerous monuments removed during the George Floyd protests. The statue is being reproduced by the Knights of Columbus.

The Minnesota State Capitol Mall includes eighteen acres of green space. Over the years, monuments, and memorials, have been added to the mall. The mall has been called Minnesota's Front lawn and is a place where the public has gathered for celebrations, to party, to demonstrate and protest, and to grieve.