The yen is the official currency of Japan. It is the third-most traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar and the euro. It is also widely used as a third reserve currency after the US dollar and the euro.

A reserve currency is a foreign currency that is held in significant quantities by central banks or other monetary authorities as part of their foreign exchange reserves. The reserve currency can be used in international transactions, international investments and all aspects of the global economy. It is often considered a hard currency or safe-haven currency.

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of the euro.

The global financial system is the worldwide framework of legal agreements, institutions, and both formal and informal economic action that together facilitate international flows of financial capital for purposes of investment and trade financing. Since emerging in the late 19th century during the first modern wave of economic globalization, its evolution is marked by the establishment of central banks, multilateral treaties, and intergovernmental organizations aimed at improving the transparency, regulation, and effectiveness of international markets. In the late 1800s, world migration and communication technology facilitated unprecedented growth in international trade and investment. At the onset of World War I, trade contracted as foreign exchange markets became paralyzed by money market illiquidity. Countries sought to defend against external shocks with protectionist policies and trade virtually halted by 1933, worsening the effects of the global Great Depression until a series of reciprocal trade agreements slowly reduced tariffs worldwide. Efforts to revamp the international monetary system after World War II improved exchange rate stability, fostering record growth in global finance.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis was a period of financial crisis that gripped much of East and Southeast Asia during the late 1990s. The crisis began in Thailand in July 1997 before spreading to several other countries with a ripple effect, raising fears of a worldwide economic meltdown due to financial contagion. However, the recovery in 1998–1999 was rapid, and worries of a meltdown quickly subsided.

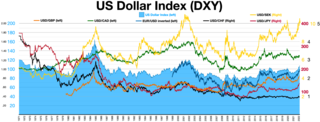

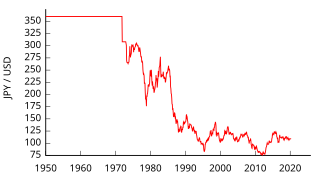

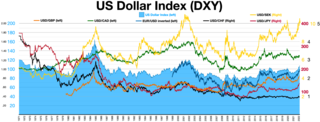

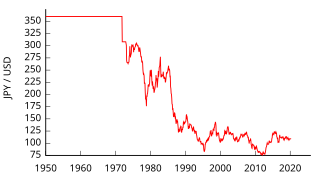

The Plaza Accord was a joint agreement signed on September 22, 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, between France, West Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, to depreciate the U.S. dollar in relation to the French franc, the German Deutsche Mark, the Japanese yen and the British pound sterling by intervening in currency markets. The U.S. dollar depreciated significantly from the time of the agreement until it was replaced by the Louvre Accord in 1987. Some commentators believe the Plaza Accord contributed to the Japanese asset price bubble of the late 1980s.

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management established the rules for commercial relations among the United States, Canada, Western European countries, and Australia as well as 44 other countries after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. The Bretton Woods system was the first example of a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent states. The Bretton Woods system required countries to guarantee convertibility of their currencies into U.S. dollars to within 1% of fixed parity rates, with the dollar convertible to gold bullion for foreign governments and central banks at US$35 per troy ounce of fine gold. It also envisioned greater cooperation among countries in order to prevent future competitive devaluations, and thus established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to monitor exchange rates and lend reserve currencies to nations with balance of payments deficits.

A managed float regime, also known as a dirty float, is a type of exchange rate regime where a currency's value is allowed to fluctuate in response to foreign-exchange market mechanisms, but the central bank or monetary authority of the country intervenes occasionally to stabilize or steer the currency's value in a particular direction. This is in contrast to a pure float where the value is entirely determined by market forces, and a fixed exchange rate where the value is pegged to another currency or a basket of currencies.

The foreign exchange market is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. It includes all aspects of buying, selling and exchanging currencies at current or determined prices. In terms of trading volume, it is by far the largest market in the world, followed by the credit market.

The Mexican peso crisis was a currency crisis sparked by the Mexican government's sudden devaluation of the peso against the U.S. dollar in December 1994, which became one of the first international financial crises ignited by capital flight.

Foreign exchange reserves are cash and other reserve assets such as gold and silver held by a central bank or other monetary authority that are primarily available to balance payments of the country, influence the foreign exchange rate of its currency, and to maintain confidence in financial markets. Reserves are held in one or more reserve currencies, nowadays mostly the United States dollar and to a lesser extent the euro.

In macroeconomics and economic policy, a floating exchange rate is a type of exchange rate regime in which a currency's value is allowed to fluctuate in response to foreign exchange market events. A currency that uses a floating exchange rate is known as a floating currency, in contrast to a fixed currency, the value of which is instead specified in terms of material goods, another currency, or a set of currencies.

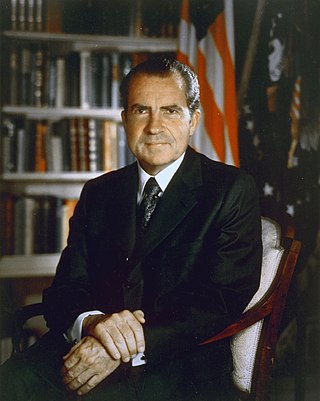

The Nixon shock refers to the effect of a series of economic measures, including wage and price freezes, surcharges on imports, and the unilateral cancellation of the direct international convertibility of the United States dollar to gold, taken by United States President Richard Nixon in 1971 in response to increasing inflation.

Endaka or Endaka Fukyo is a state in which the value of the Japanese yen is high compared to other currencies. Since the economy of Japan is highly dependent on exports, this can cause Japan to fall into an economic recession.

Currency intervention, also known as foreign exchange market intervention or currency manipulation, is a monetary policy operation. It occurs when a government or central bank buys or sells foreign currency in exchange for its own domestic currency, generally with the intention of influencing the exchange rate and trade policy.

Currency manipulator is a designation applied by United States government authorities, such as the United States Department of the Treasury, to countries that engage in what is called "unfair currency practices" that give them a trade advantage. Such practices may be currency intervention or monetary policy in which a central bank buys or sells foreign currency in exchange for domestic currency, generally with the intention of influencing the exchange rate and commercial policy. Policymakers may have different reasons for currency intervention, such as controlling inflation, maintaining international competitiveness, or financial stability. In many cases, the central bank weakens its own currency to subsidize exports and raise the price of imports, sometimes by as much as 30–40%, and it is thereby a method of protectionism. Currency manipulation is not necessarily easy to identify and some people have considered quantitative easing to be a form of currency manipulation.

A currency basket is a portfolio of selected currencies with different weightings. A currency basket is commonly used by investors to minimize the risk of currency fluctuations and also governments when setting the market value of a country's currency.

Currency war, also known as competitive devaluations, is a condition in international affairs where countries seek to gain a trade advantage over other countries by causing the exchange rate of their currency to fall in relation to other currencies. As the exchange rate of a country's currency falls, exports become more competitive in other countries, and imports into the country become more and more expensive. Both effects benefit the domestic industry, and thus employment, which receives a boost in demand from both domestic and foreign markets. However, the price increases for import goods are unpopular as they harm citizens' purchasing power; and when all countries adopt a similar strategy, it can lead to a general decline in international trade, harming all countries.

The United States dollar was established as the world's foremost reserve currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. It claimed this status from sterling after the devastation of two world wars and the massive spending of the United Kingdom's gold reserves. Despite all links to gold being severed in 1971, the dollar continues to be the world's foremost reserve currency. Furthermore, the Bretton Woods Agreement also set up the global post-war monetary system by setting up rules, institutions and procedures for conducting international trade and accessing the global capital markets using the US dollar.

The Currency War of 2009–2011 was an episode of competitive devaluation which became prominent in the financial press in September 2010. It involved states competing with each other in order to achieve a relatively low valuation for their own currency, so as to assist their domestic industry. With the financial crises of 2008 the export sectors of many emerging economies experienced declining orders and from 2009, several states began or increased their levels of currency intervention. According to many analysts the currency war had largely fizzled out by mid-2011 although the war rhetoric persisted into the following year. In 2013, there were concerns of an outbreak of another currency war, this time between Japan and the Euro-zone.