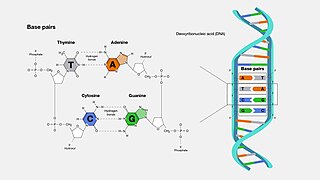

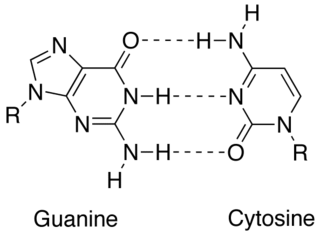

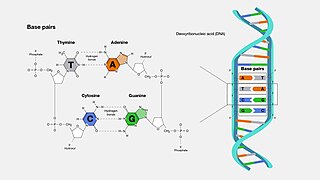

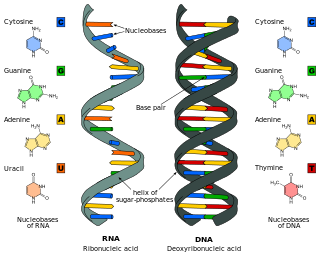

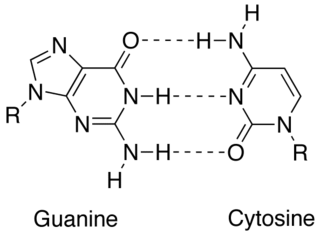

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" base pairs allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

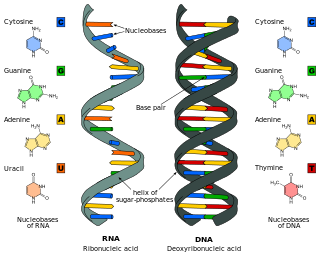

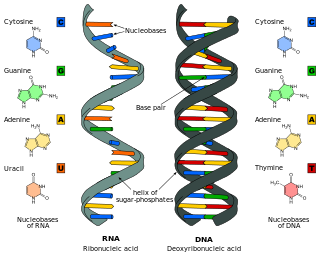

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids. Alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life.

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). If the sugar is ribose, the polymer is RNA; if the sugar is deoxyribose, a variant of ribose, the polymer is DNA.

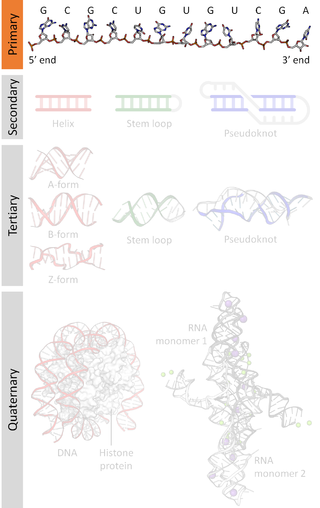

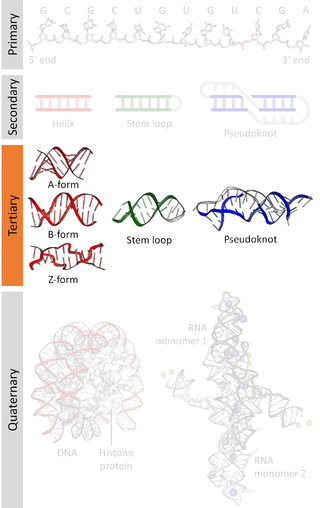

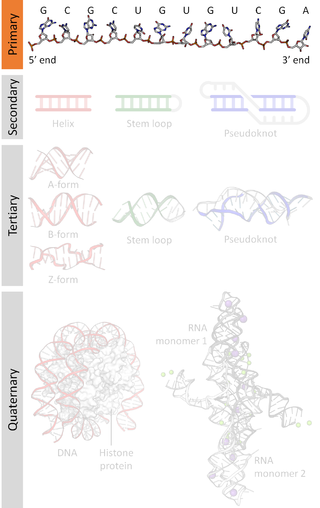

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nucleotides. By convention, sequences are usually presented from the 5' end to the 3' end. For DNA, with its double helix, there are two possible directions for the notated sequence; of these two, the sense strand is used. Because nucleic acids are normally linear (unbranched) polymers, specifying the sequence is equivalent to defining the covalent structure of the entire molecule. For this reason, the nucleic acid sequence is also termed the primary structure.

A Hoogsteen base pair is a variation of base-pairing in nucleic acids such as the A•T pair. In this manner, two nucleobases, one on each strand, can be held together by hydrogen bonds in the major groove. A Hoogsteen base pair applies the N7 position of the purine base and C6 amino group, which bind the Watson–Crick (N3–C4) face of the pyrimidine base.

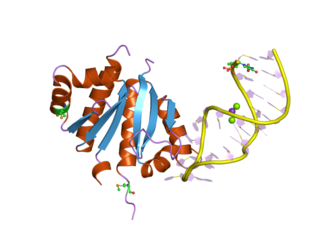

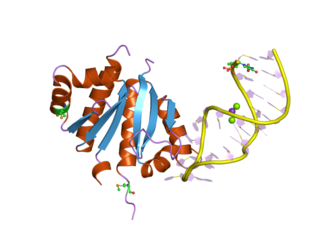

A DNA-binding domain (DBD) is an independently folded protein domain that contains at least one structural motif that recognizes double- or single-stranded DNA. A DBD can recognize a specific DNA sequence or have a general affinity to DNA. Some DNA-binding domains may also include nucleic acids in their folded structure.

In molecular biology, G-quadruplex secondary structures (G4) are formed in nucleic acids by sequences that are rich in guanine. They are helical in shape and contain guanine tetrads that can form from one, two or four strands. The unimolecular forms often occur naturally near the ends of the chromosomes, better known as the telomeric regions, and in transcriptional regulatory regions of multiple genes, both in microbes and across vertebrates including oncogenes in humans. Four guanine bases can associate through Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding to form a square planar structure called a guanine tetrad, and two or more guanine tetrads can stack on top of each other to form a G-quadruplex.

A palindromic sequence is a nucleic acid sequence in a double-stranded DNA or RNA molecule whereby reading in a certain direction on one strand is identical to the sequence in the same direction on the complementary strand. This definition of palindrome thus depends on complementary strands being palindromic of each other.

In biochemistry, two biopolymers are antiparallel if they run parallel to each other but with opposite directionality (alignments). An example is the two complementary strands of a DNA double helix, which run in opposite directions alongside each other.

The K Homology (KH) domain is a protein domain that was first identified in the human heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) K. An evolutionarily conserved sequence of around 70 amino acids, the KH domain is present in a wide variety of nucleic acid-binding proteins. The KH domain binds RNA, and can function in RNA recognition. It is found in multiple copies in several proteins, where they can function cooperatively or independently. For example, in the AU-rich element RNA-binding protein KSRP, which has 4 KH domains, KH domains 3 and 4 behave as independent binding modules to interact with different regions of the AU-rich RNA targets. The solution structure of the first KH domain of FMR1 and of the C-terminal KH domain of hnRNP K determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) revealed a beta-alpha-alpha-beta-beta-alpha structure. Autoantibodies to NOVA1, a KH domain protein, cause paraneoplastic opsoclonus ataxia. The KH domain is found at the N-terminus of the ribosomal protein S3. This domain is unusual in that it has a different fold compared to the normal KH domain.

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered. Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain . Nucleic acid analogues are also called xeno nucleic acids and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

Tetraloops are a type of four-base hairpin loop motifs in RNA secondary structure that cap many double helices. There are many variants of the tetraloop. The published ones include ANYA, CUYG, GNRA, UNAC and UNCG.

Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX36 also known as DEAH box protein 36 (DHX36) or MLE-like protein 1 (MLEL1) or G4 resolvase 1 (G4R1) or RNA helicase associated with AU-rich elements (RHAU) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the DHX36 gene.

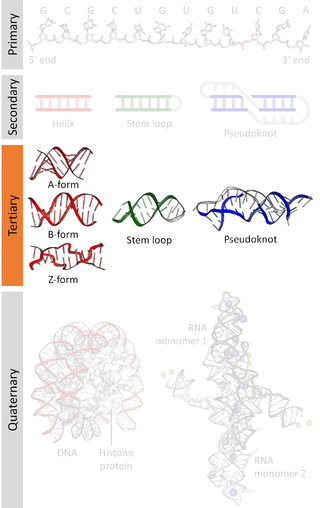

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer. RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

Non-canonical base pairs are planar hydrogen bonded pairs of nucleobases, having hydrogen bonding patterns which differ from the patterns observed in Watson-Crick base pairs, as in the classic double helical DNA. The structures of polynucleotide strands of both DNA and RNA molecules can be understood in terms of sugar-phosphate backbones consisting of phosphodiester-linked D 2’ deoxyribofuranose sugar moieties, with purine or pyrimidine nucleobases covalently linked to them. Here, the N9 atoms of the purines, guanine and adenine, and the N1 atoms of the pyrimidines, cytosine and thymine, respectively, form glycosidic linkages with the C1’ atom of the sugars. These nucleobases can be schematically represented as triangles with one of their vertices linked to the sugar, and the three sides accounting for three edges through which they can form hydrogen bonds with other moieties, including with other nucleobases. The side opposite to the sugar linked vertex is traditionally called the Watson-Crick edge, since they are involved in forming the Watson-Crick base pairs which constitute building blocks of double helical DNA. The two sides adjacent to the sugar-linked vertex are referred to, respectively, as the Sugar and Hoogsteen edges.

i-motif DNA, short for intercalated-motif DNA, are cytosine-rich four-stranded quadruplex DNA structures, similar to the G-quadruplex structures that are formed in guanine-rich regions of DNA.

In molecular biology, a guanine tetrad is a structure composed of four guanine bases in a square planar array. They most prominently contribute to the structure of G-quadruplexes, where their hydrogen bonding stabilizes the structure. Usually, there are at least two guanine tetrads in a G-quadruplex, and they often feature Hoogsteen-style hydrogen bonding.