Recreational drug use is the use of one or more psychoactive drugs to induce an altered state of consciousness, either for pleasure or for some other casual purpose or pastime. When a psychoactive drug enters the user's body, it induces an intoxicating effect. Recreational drugs are commonly divided into three categories: depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens.

The prohibition of drugs through sumptuary legislation or religious law is a common means of attempting to prevent the recreational use of certain intoxicating substances.

Commonly-cited arguments for and against the prohibition of drugs include the following:

Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana, weed, and pot, among other names, is a non-chemically uniform drug from the cannabis plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and entheogenic purposes and in various traditional medicines for centuries. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the main psychoactive component of cannabis, which is one of the 483 known compounds in the plant, including at least 65 other cannabinoids, such as cannabidiol (CBD). Cannabis can be used by smoking, vaporizing, within food, or as an extract.

Different religions have varying stances on the use of cannabis, historically and presently. In ancient history some religions used cannabis as an entheogen, particularly in the Indian subcontinent where the tradition continues on a more limited basis.

Many religions have expressed positions on what is acceptable to consume as a means of intoxication for spiritual, pleasure, or medicinal purposes. Psychoactive substances may also play a significant part in the development of religion and religious views as well as in rituals.

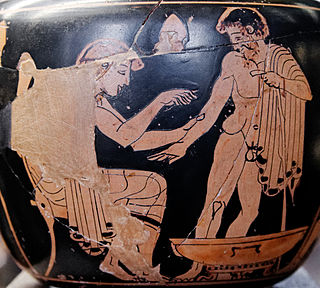

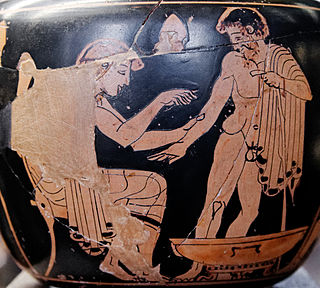

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. The Greek term for medicine was iatrikē. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods". As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Medicine in ancient Rome was highly influenced by ancient Greek medicine, but also developed new practices through knowledge of the Hippocratic Corpus combined with use of the treatment of diet, regimen, along with surgical procedures. This was most notably seen through the works of two of the prominent Greek physicians, Dioscorides and Galen, who practiced medicine and recorded their discoveries. This is contrary to two other physicians like Soranus of Ephesus and Asclepiades of Bithynia, who practiced medicine both in outside territories and in ancient Roman territory, subsequently. Dioscorides was a Roman army physician, Soranus was a representative for the Methodic school of medicine, Galen performed public demonstrations, and Asclepiades was a leading Roman physician. These four physicians all had knowledge of medicine, ailments, and treatments that were healing, long lasting and influential to human history.

The drug policy in the United States is the activity of the federal government relating to the regulation of drugs. Starting in the early 1900s, the United States government began enforcing drug policies. These policies criminalized drugs such as opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine outside of medical use. The drug policies put into place are enforced by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Classification of Drugs are defined and enforced using the Controlled Substance Act, which lists different drugs into their respective substances based on its potential of abuse and potential for medical use. Four different categories of drugs are Alcohol, Cannabis, Opioids, and Stimulants.

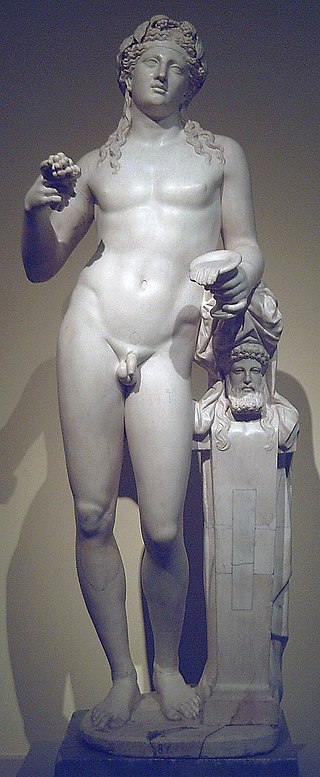

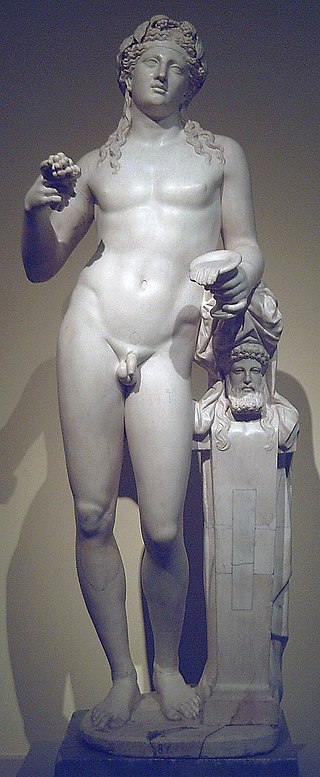

Ancient Rome played a pivotal role in the history of wine. The earliest influences on the viticulture of the Italian Peninsula can be traced to ancient Greeks and the Etruscans. The rise of the Roman Empire saw both technological advances in and burgeoning awareness of winemaking, which spread to all parts of the empire. Rome's influence has had a profound effect on the histories of today's major winemaking regions in France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Childbirth and obstetrics in classical antiquity were studied by the physicians of ancient Greece and Rome. Their ideas and practices during this time endured in Western medicine for centuries and many themes are seen in modern women's health. Classical gynecology and obstetrics were originally studied and taught mainly by midwives in the ancient world, but eventually scholarly physicians of both sexes became involved as well. Obstetrics is traditionally defined as the surgical specialty dealing with the care of a woman and her offspring during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (recovery). Gynecology involves the medical practices dealing with the health of women's reproductive organs and breasts.

Sextius Niger was a Roman writer on pharmacology during the reign of Augustus or a little later. He may be identical with the son of the philosopher Quintus Sextius, who continued his philosophical teachings.

A psychoactive drug, mind-altering drug, or consciousness-altering drug is a chemical substance that changes brain function and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, or behavior. The term psychotropic drug is often used interchangeably, while some sources present narrower definitions. These substances may be used medically; recreationally; to purposefully improve performance or alter consciousness; as entheogens for ritual, spiritual, or shamanic purposes; or for research, including psychedelic therapy. Physicians and other healthcare practitioners prescribe psychoactive drugs from several categories for therapeutic purposes. These include anesthetics, analgesics, anticonvulsant and antiparkinsonian drugs as well as medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders, such as antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and stimulants. Some psychoactive substances may be used in detoxification and rehabilitation programs for persons dependent on or addicted to other psychoactive drugs.

The history of herbalism is closely tied with the history of medicine from prehistoric times up until the development of the germ theory of disease in the 19th century. Modern medicine from the 19th century to today has been based on evidence gathered using the scientific method. Evidence-based use of pharmaceutical drugs, often derived from medicinal plants, has largely replaced herbal treatments in modern health care. However, many people continue to employ various forms of traditional or alternative medicine. These systems often have a significant herbal component. The history of herbalism also overlaps with food history, as many of the herbs and spices historically used by humans to season food yield useful medicinal compounds, and use of spices with antimicrobial activity in cooking is part of an ancient response to the threat of food-borne pathogens.

Cannabis in India has been known to be used at least as early as 2000 BCE. In Indian society, common terms for cannabis preparations include charas (resin), ganja (flower), and bhang, with Indian drinks such as bhang lassi and bhang thandai made from bhang being one of the most common legal uses.

Although Cannabis use is illegal in Egypt, it is often used privately by many. Law enforcements are often particularly lax when it comes to cannabis smokers, and its use is a part of the common culture for many people in Egypt. However, Large-scale smuggling of cannabis is punishable by death, while penalties for possessing even small amounts can also be severe. Despite this, these laws are not enforced in many parts of Egypt, where cannabis is often consumed openly in local cafes.

Cannabis in South Korea is illegal for recreational use. In November 2018, the country's Narcotics Control Act was amended and use of medical cannabis became legal, making South Korea the first country in East Asia to legalize medical cannabis.

The history of cannabis and its usage by humans dates back to at least the third millennium BC in written history, and possibly as far back as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B based on archaeological evidence. For millennia, the plant has been valued for its use for fiber and rope, as food and medicine, and for its psychoactive properties for religious and recreational use.

Mental illness in ancient Rome was recognized in law as an issue of mental competence, and was diagnosed and treated in terms of ancient medical knowledge and philosophy, primarily Greek in origin, while at the same time popularly thought to have been caused by divine punishment, demonic spirits, or curses. Physicians and medical writers of the Roman world observed patients with conditions similar to anxiety disorders, mood disorders, dyslexia, schizophrenia, and speech disorders, among others, and assessed symptoms and risk factors for mood disorders as owing to alcohol abuse, aggression, and extreme emotions. It can be difficult to apply modern labels such as schizophrenia accurately to conditions described in ancient medical writings and other literature, which may for instance be referring instead to mania.

Modern historians' knowledge of ancient Roman gynecology and obstetrics primarily comes from Soranus of Ephesus' four-volume treatise on gynecology. His writings covered medical conditions such as uterine prolapse and cancer and treatments involving materials such as herbs and tools such as pessaries. Ancient Roman doctors believed that menstruation was designed to rid the female body of excess fluids. They believed that menstrual blood had special powers. Roman doctors may also have noticed conditions such as premenstrual syndrome.