Geology

The geology of the Sulcis Mountains is rather complex, due to their very ancient origin, dating to more than 600 million years ago, before the Cambrian period. Their advanced age is also evident in the subdued nature of their relief, with just a few peaks over 1000m in elevation. Most of the chain’s surviving geological record consists of magmatic intrusions and metamorphic rocks whose protoliths were deposited prior to the Variscan orogeny and are now exposed at the surface after millions of years of erosion and unroofing.

The western side of the chain, more affected by erosion and flood processes, is modest in relief and elevation and characterized by more subdued topography, while the inner and eastern sectors feature sharper and more irregular topography, with extensive relief and steep, narrow valleys. The western side contains the oldest formations, dating from the Cambrian, which consist of originally sedimentary rocks of marine origin, which were later metamorphosed. Karst topography is also present in the western sector (Is Zuddas Grottoes [ it ]).

Most of the chain’s sedimentary protoliths dating from the Carboniferous to the Permian were either regionally or thermally metamorphosed during the Variscan orogeny or by the intrusion of syn- and post-orogenic Variscan and later, Cenozoic granitic plutons, respectively. Post-Variscan erosion and tectonic uplift during Cenozoic time led to the unroofing and exposure of magmatic leucogranites and metamorphic schists, which has ultimately resulted in the eastern sector being more geologically heterogeneous.

The plateau-like formations found at the feet of the chain have a dual origin: those on the western side are more ancient, consisting of flood deposits and, partly, lavas from the Cenozoic, while those on the eastern and south-eastern sides consist of small flood deposits from the Quaternary.

The geology of the Appalachians dates back more than 1.2 billion years to the Mesoproterozoic era when two continental cratons collided to form the supercontinent Rodinia, 500 million years prior to the development of the range during the formation of Pangea. The rocks exposed in today's Appalachian Mountains reveal elongate belts of folded and thrust faulted marine sedimentary rocks, volcanic rocks, and slivers of ancient ocean floor—strong evidences that these rocks were deformed during plate collision. The birth of the Appalachian ranges marks the first of several mountain building plate collisions that culminated in the construction of Pangea with the Appalachians and neighboring Anti-Atlas mountains near the center. These mountain ranges likely once reached elevations similar to those of the Alps and the Rocky Mountains before they were eroded.

The Penninic nappes or the Penninicum, commonly abbreviated as Penninic, are one of three nappe stacks and geological zones in which the Alps can be divided. In the western Alps the Penninic nappes are more obviously present than in the eastern Alps, where they crop out as a narrow band. The name Penninic is derived from the Pennine Alps, an area in which rocks from the Penninic nappes are abundant.

The Sierra Nevada Batholith is a large batholith that is approximately 400 miles long and 60-80 miles wide which forms the core of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California, exposed at the surface as granite.

The geology of England is mainly sedimentary. The youngest rocks are in the south east around London, progressing in age in a north westerly direction. The Tees–Exe line marks the division between younger, softer and low-lying rocks in the south east and the generally older and harder rocks of the north and west which give rise to higher relief in those regions. The geology of England is recognisable in the landscape of its counties, the building materials of its towns and its regional extractive industries.

The geology of the Iberian Peninsula consists of the study of the rock formations on the Iberian Peninsula, connected to the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees. The peninsula contains rocks from every geological period from the Ediacaran to the Quaternary, and many types of rock are represented. World-class mineral deposits are also found there.

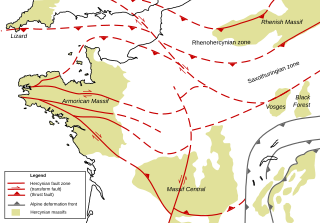

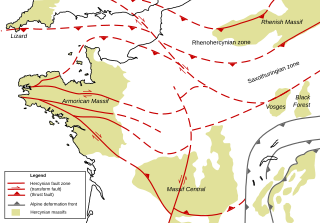

The Armorican Massif is a geologic massif that covers a large area in the northwest of France, including Brittany, the western part of Normandy and the Pays de la Loire. It is important because it is connected to Dover on the British side of the English Channel and there has been tilting back and forth that has controlled the geography on both sides.

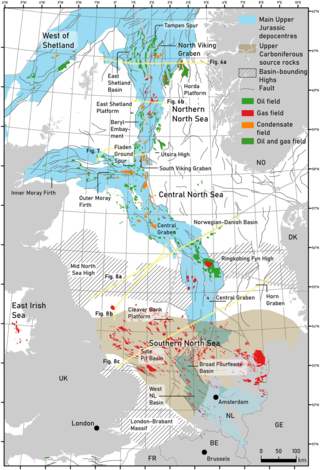

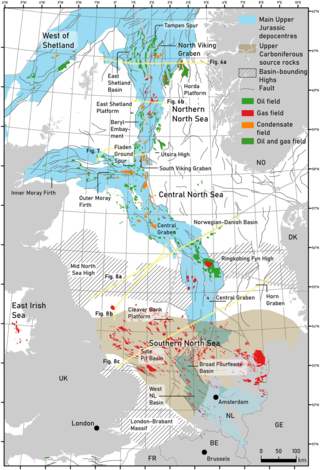

The geology of the North Sea describes the geological features such as channels, trenches, and ridges today and the geological history, plate tectonics, and geological events that created them.

The Saxothuringian Zone, Saxo-Thuringian zone or Saxothuringicum is in geology a structural or tectonic zone in the Hercynian or Variscan orogen of central and western Europe. Because rocks of Hercynian age are in most places covered by younger strata, the zone is not everywhere visible at the surface. Places where it crops out are the northern Bohemian Massif, the Spessart, the Odenwald, the northern parts of the Black Forest and Vosges and the southern part of the Taunus. West of the Vosges terranes on both sides of the English Channel are also seen as part of the zone, for example the Lizard complex in Cornwall or the Léon Zone of the Armorican Massif (Brittany).

The West African Craton (WAC) is one of the five cratons of the Precambrian basement rock of Africa that make up the African Plate, the others being the Kalahari craton, Congo craton, Saharan Metacraton and Tanzania Craton. Cratons themselves are tectonically inactive, but can occur near active margins, with the WAC extending across 14 countries in Western Africa, coming together in the late Precambrian and early Palaeozoic eras to form the African continent. It consists of two Archean centers juxtaposed against multiple Paleoproterozoic domains made of greenstone belts, sedimentary basins, regional granitoid-tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG) plutons, and large shear zones. The craton is overlain by Neoproterozoic and younger sedimentary basins. The boundaries of the WAC are predominantly defined by a combination of geophysics and surface geology, with additional constraints by the geochemistry of the region. At one time, volcanic action around the rim of the craton may have contributed to a major global warming event.

The Moldanubian Zone is in the regional geology of Europe a tectonic zone formed during the Variscan or Hercynian Orogeny. The Moldanubian Zone crops out in the Bohemian Massif and the southern part of the Black Forest and Vosges and contains the highest grade metamorphic rocks of Variscan age in Europe.

The Massif Central is one of the two large basement massifs in France, the other being the Armorican Massif. The Massif Central's geological evolution started in the late Neoproterozoic and continues to this day. It has been shaped mainly by the Caledonian orogeny and the Variscan orogeny. The Alpine orogeny has also left its imprints, probably causing the important Cenozoic volcanism. The Massif Central has a very long geological history, underlined by zircon ages dating back into the Archaean 3 billion years ago. Structurally it consists mainly of stacked metamorphic basement nappes.

The Génis Unit is a Paleozoic metasedimentary succession of the southern Limousin and belongs geologically to the Variscan basement of the French Massif Central. The unit covers the age range Cambrian/Ordovician till Devonian.

The main points that are discussed in the geology of Iran include the study of the geological and structural units or zones; stratigraphy; magmatism and igneous rocks; ophiolite series and ultramafic rocks; and orogenic events in Iran.

The geology of Germany is heavily influenced by several phases of orogeny in the Paleozoic and the Cenozoic, by sedimentation in shelf seas and epicontinental seas and on plains in the Permian and Mesozoic as well as by the Quaternary glaciations.

The Mars Hill Terrane (MHT) is a belt of rocks exposed in the southern Appalachian Mountains, between Roan Mountain, North Carolina and Mars Hill, North Carolina. The terrane is located at the junction between the Western Blue Ridge and the Eastern Blue Ridge Mountains.

The geology of Niger comprises very ancient igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks in the west, more than 2.2 billion years old formed in the late Archean and Proterozoic eons of the Precambrian. The Volta Basin, Air Massif and the Iullemeden Basin began to form in the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic, along with numerous ring complexes, as the region experienced events such as glaciation and the Pan-African orogeny. Today, Niger has extensive mineral resources due to complex mineralization and laterite weathering including uranium, molybdenum, iron, coal, silver, nickel, cobalt and other resources.

The geology of the State of New York is made up of ancient Precambrian crystalline basement rock, forming the Adirondack Mountains and the bedrock of much of the state. These rocks experienced numerous deformations during mountain building events and much of the region was flooded by shallow seas depositing thick sequences of sedimentary rock during the Paleozoic. Fewer rocks have deposited since the Mesozoic as several kilometers of rock have eroded into the continental shelf and Atlantic coastal plain, although volcanic and sedimentary rocks in the Newark Basin are a prominent fossil-bearing feature near New York City from the Mesozoic rifting of the supercontinent Pangea.

The geology of the Czech Republic is very tectonically complex, split between the Western Carpathian Mountains and the Bohemian Massif.

The geology of Argentina includes ancient Precambrian basement rock affected by the Grenville orogeny, sediment filled basins from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic as well as newly uplifted areas in the Andes.

The Cornubian Massif was an upland area and source of sediment in southwest England during parts of the Late Permian to Early Cretaceous period and through most of the Cenozoic. In extent it covered approximately the current area of Devon and Cornwall.