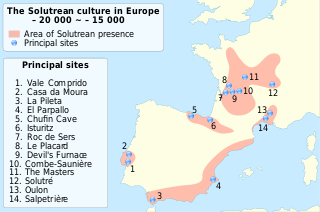

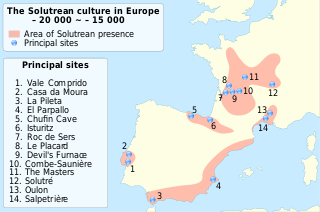

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Paleolithic of the Final Gravettian, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP. Solutrean sites have been found in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal.

The Aurignacian is an archaeological industry of the Upper Paleolithic associated with Early European modern humans (EEMH) lasting from 43,000 to 26,000 years ago. The Upper Paleolithic developed in Europe some time after the Levant, where the Emiran period and the Ahmarian period form the first periods of the Upper Paleolithic, corresponding to the first stages of the expansion of Homo sapiens out of Africa. They then migrated to Europe and created the first European culture of modern humans, the Aurignacian.

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by c. 22,000 BP, close to the Last Glacial Maximum, although some elements lasted until c. 17,000 BP. In Spain and France, it was succeeded by the Solutrean and by the Epigravettian in Italy, the Balkans, Ukraine and Russia.

Magdalenian cultures are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madeleine, a rock shelter located in the Vézère valley, commune of Tursac, in France's Dordogne department.

Erik Trinkaus is an American paleoanthropologist specializing in Neandertal and early modern human biology and human evolution. Trinkaus researches the evolution of the species Homo sapiens and recent human diversity, focusing on the paleoanthropology and emergence of late archaic and early modern humans, and the subsequent evolution of anatomically modern humanity. Trinkaus is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor Emeritus of Arts and Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He is a frequent contributor to publications such as Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PLOS One, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and the Journal of Human Evolution and has written/co-written or edited/co-edited fifteen books in paleoanthropology. He is frequently quoted in the popular media.

Dolní Věstonice is an Upper Paleolithic archaeological site near the village of Dolní Věstonice in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic, at the base of Mount Děvín, 550 metres (1,800 ft). It dates to approximately 26,000 BP, as supported by radiocarbon dating. The site is unique in that it has been a particularly abundant source of prehistoric artifacts dating from the Gravettian period, which spanned roughly from 27,000 to 20,000 BC. In addition to the abundance of art, this site also includes carved representations of men, women, and animals, along with personal ornaments, human burials and enigmatic engravings.

The Bacho Kiro cave is situated 5 km (3.1 mi) west of the town Dryanovo, Bulgaria, only 300 m (980 ft) away from the Dryanovo Monastery. It is embedded in the canyons of the Andaka and Dryanovo River. It was opened in 1890 and the first recreational visitors entered the cave in 1938, two years before it was renamed in honor of Bulgarian National Revival leader, teacher and revolutionary Bacho Kiro. The cave is a four-storey labyrinth of galleries and corridors with a total length of 3,600 m (11,800 ft), 700 m (2,300 ft) of which are maintained for public access and equipped with electrical lights since 1964. An underground river has over time carved out the many galleries that contain countless stalactone, stalactite, and stalagmite speleothem formations of great beauty. Galleries and caverns of a 1,200 m (3,900 ft) long section have been musingly named as a popular description of this fairy-tale underground world. The formations succession: Bacho Kiro’s Throne, The Dwarfs, The Sleeping Princess, The Throne Hall, The Reception Hall, The Haidouti Meeting-Ground, The Fountain and the Sacrificial Altar.

Peștera cu Oase is a system of 12 karstic galleries and chambers located near the city Anina, in the Caraș-Severin county, southwestern Romania, where some of the oldest European early modern human (EEMH) remains, between 42,000 and 37,000 years old, have been found.

The Kostyonki–Borshchyovo archaeological complex is an area where numerous Upper Paleolithic archaeological sites have been found, located around the villages of Kostyonki and Borshchyovo. The area is found on the western (right) bank of the Don River in Khokholsky District, Voronezh Oblast, Russia, some 25 km south of the city of Voronezh. The 26 Paleolithic sites of the area are numbered Kostenki 1–21 and Borshchevo 1–5.

Tianyuan man are the remains of one of the earliest modern humans to inhabit East Asia. In 2007, researchers found 34 bone fragments belonging to a single individual at the Tianyuan Cave near Beijing, China. Radiocarbon dating shows the bones to be between 42,000 and 39,000 years old, which may be slightly younger than the only other finds of bones of a similar age at the Niah Caves in Sarawak on the South-east Asian island of Borneo.

Paglicci Cave is an archaeological site situated in Paglicci, near Rignano Garganico, Apulia, southern Italy. The cave, discovered in the 1950s, is the most important cave of Gargano. The cave is an attraction of the Gargano National Park.

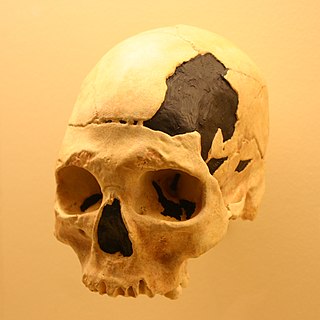

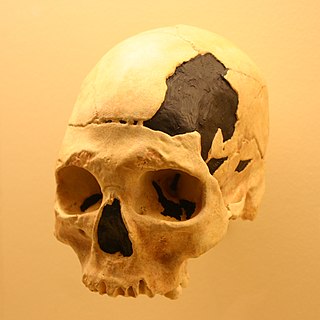

Peștera Muierilor, or Peștera Muierii, is an elaborate cave system located in the Baia de Fier commune, Gorj County, Romania. It contains abundant cave bear remains, as well as a human skull. The skull is radiocarbon dated to 30,150 ± 800, indication an absolute age between 40,000 and 30,000 BP. It was uncovered in 1952. Alongside similar remains found in Cioclovina Cave, they are among the most ancient early modern humans in Romanian prehistory.

The Mal'ta–Buret' culture is an archaeological culture of the Upper Paleolithic. It is located roughly northwest of Lake Baikal, about 90km to the northwest of Irkutsk, on the banks of the upper Angara River.

Cro-Magnons or European early modern humans (EEMH) were the first early modern humans to settle in Europe, migrating from western Asia, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They interacted and interbred with the indigenous Neanderthals of Europe and Western Asia, who went extinct 40,000 to 35,000 years ago. The first wave of modern humans in Europe left no genetic legacy to modern Europeans; however, from 37,000 years ago a second wave succeeded in forming a single founder population, from which all subsequent Cro-Magnons descended and which contributes ancestry to present-day Europeans. Cro-Magnons produced Upper Palaeolithic cultures, the first major one being the Aurignacian, which was succeeded by the Gravettian by 30,000 years ago. The Gravettian split into the Epi-Gravettian in the east and Solutrean in the west, due to major climatic degradation during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), peaking 21,000 years ago. As Europe warmed, the Solutrean evolved into the Magdalenian by 20,000 years ago, and these peoples recolonised Europe. The Magdalenian and Epi-Gravettian gave way to Mesolithic cultures as big game animals were dying out and the Last Glacial Period drew to a close.

The Epigravettian was one of the last archaeological industries and cultures of the European Upper Paleolithic. It emerged after the Last Glacial Maximum around ~21,000 cal. BP or 19,050 BC. It succeeds the Gravettian culture in Italy. Initially named Tardigravettian in 1964 by Georges Laplace in reference to several lithic industries found in Italy, it was later renamed in order to better emphasize its independent character.

Haplogroup HIJK, defined by the SNPs F929, M578, PF3494 and S6397, is a common Y-chromosome haplogroup. Like its parent macrohaplogroup GHIJK, Haplogroup HIJK and its subclades comprise the vast majority of the world's male population.

Haplogroup C1 also known as C-F3393, is a major Y-chromosome haplogroup. It is one of two primary branches of the broader Haplogroup C, the other being C2.

Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) was a culture or technocomplex (industry) dating to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, about 45,000 years ago. It is characterised by leaf points made on long blades, which were traditionally thought to have been made by the last Neanderthals, although some researchers have suggested that it could be a culture of the first anatomically modern humans in Europe. It is rarely found, but extends across northwest Europe from Wales to Poland.

Haplogroup C-V20 is a Y-chromosome haplogroup. It is one of two primary branches of Haplogroup C1a, one of the descendants of Haplogroup C1. Haplogroup C-V20 is now distributed in Europe, North Africa, West Asia, and South Asia with very low frequency.

In archaeogenetics, western hunter-gatherer is a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who scattered over western, southern and central Europe, from the British Isles in the west to the Carpathians in the east, following the retreat of the ice sheet of the Last Glacial Maximum. It is closely associated and sometimes considered synonymous with the concept of the Villabruna cluster, named after Ripari Villabruna cave in Italy, known from the terminal Pleistocene of Europe, which is largely ancestral to later WHG populations.