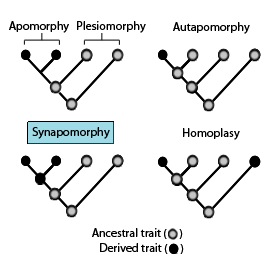

Cladistics is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies) that are not present in more distant groups and ancestors. Theoretically, a common ancestor and all its descendants are part of the clade, however, from an empirical perspective, common ancestors are inferences based on a cladistic hypothesis of relationships of taxa whose character states can be observed. Importantly, all descendants stay in their overarching ancestral clade. For example, if within a strict cladistic framework the terms worms or fishes were used, these terms would include humans. Many of these terms are normally used paraphyletically, outside of cladistics, e.g. as a 'grade'. Radiation results in the generation of new subclades by bifurcation, but in practice sexual hybridization may blur very closely related groupings.

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic groups are typically characterised by shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies), which distinguish organisms in the clade from other organisms. An equivalent term is holophyly.

In biology, phylogenetics is a part of systematics that addresses the inference of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups of organisms. These relationships are hypothesized by phylogenetic inference methods that evaluate observed heritable traits, such as DNA sequences, protein amino acid sequences, or morphology, often under a specified model of evolution of these traits. The result of such an analysis is a phylogeny —a diagrammatic hypothesis of relationships that reflects the evolutionary history of a group of organisms. The tips of a phylogenetic tree can be living taxa or fossils, and represent the 'end', or the present, in an evolutionary lineage. A phylogenetic diagram can be rooted or unrooted. A rooted tree diagram indicates the hypothetical common ancestor, or ancestral lineage, of the tree. An unrooted tree diagram makes no assumption about the ancestral line, and does not show the origin or "root" of the taxa in question or the direction of inferred evolutionary transformations. In addition to their proper use for inferring phylogenetic patterns among taxa, phylogenetic analyses are often employed to represent relationships among gene copies or individual organisms. Such uses have become central to understanding biodiversity, evolution, ecology, and genomes. In February 2021, scientists reported, for the first time, the sequencing of DNA from animal remains, a mammoth in this instance, over a million years old, the oldest DNA sequenced to date.

In biology, phenetics, also known as taximetrics, is an attempt to classify organisms based on overall similarity, usually in morphology or other observable traits, regardless of their phylogeny or evolutionary relation. It is closely related to numerical taxonomy which is concerned with the use of numerical methods for taxonomic classification. Many people contributed to the development of phenetics, but the most influential were Peter Sneath and Robert R. Sokal. Their books are still primary references for this sub-discipline, although now out of print.

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and all descendants of that ancestor excluding a few—typically only one or two—monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic with respect to the excluded subgroups. A paraphyletic group cannot be a clade, or monophyletic group, which is any group of species that includes a common ancestor and all of its descendants. One or more members of a paraphyletic group is more closely related to the excluded group(s) than it is to other members of the paraphyletic group. The term is commonly used in phylogenetics and in linguistics. Paraphyletic groups are identified by a combination of synapomorphies and symplesiomorphies.

A cladogram is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to descendants, nor does it show how much they have changed, so many differing evolutionary trees can be consistent with the same cladogram. A cladogram uses lines that branch off in different directions ending at a clade, a group of organisms with a last common ancestor. There are many shapes of cladograms but they all have lines that branch off from other lines. The lines can be traced back to where they branch off. These branching off points represent a hypothetical ancestor which can be inferred to exhibit the traits shared among the terminal taxa above it. This hypothetical ancestor might then provide clues about the order of evolution of various features, adaptation, and other evolutionary narratives about ancestors. Although traditionally such cladograms were generated largely on the basis of morphological characters, DNA and RNA sequencing data and computational phylogenetics are now very commonly used in the generation of cladograms, either on their own or in combination with morphology.

In biology, homology is similarity due to shared ancestry between a pair of structures or genes in different taxa. A common example of homologous structures is the forelimbs of vertebrates, where the wings of bats and birds, the arms of primates, the front flippers of whales and the forelegs of four-legged vertebrates like dogs and crocodiles are all derived from the same ancestral tetrapod structure. Evolutionary biology explains homologous structures adapted to different purposes as the result of descent with modification from a common ancestor. The term was first applied to biology in a non-evolutionary context by the anatomist Richard Owen in 1843. Homology was later explained by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859, but had been observed before this, from Aristotle onwards, and it was explicitly analysed by Pierre Belon in 1555.

A polyphyletic group or assemblage is a set of organisms, or other evolving elements, that have been grouped together based on characteristics that do not imply that they share a common ancestor that is not also the common ancestor of many other taxa. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of convergent evolution. The arrangement of the members of a polyphyletic group is called a polyphyly.

Evolutionary taxonomy, evolutionary systematics or Darwinian classification is a branch of biological classification that seeks to classify organisms using a combination of phylogenetic relationship, progenitor-descendant relationship, and degree of evolutionary change. This type of taxonomy may consider whole taxa rather than single species, so that groups of species can be inferred as giving rise to new groups. The concept found its most well-known form in the modern evolutionary synthesis of the early 1940s.

In cladistics or phylogenetics, an outgroup is a more distantly related group of organisms that serves as a reference group when determining the evolutionary relationships of the ingroup, the set of organisms under study, and is distinct from sociological outgroups. The outgroup is used as a point of comparison for the ingroup and specifically allows for the phylogeny to be rooted. Because the polarity (direction) of character change can be determined only on a rooted phylogeny, the choice of outgroup is essential for understanding the evolution of traits along a phylogeny.

In phylogenetics, maximum parsimony is an optimality criterion under which the phylogenetic tree that minimizes the total number of character-state changes is to be preferred. Under the maximum-parsimony criterion, the optimal tree will minimize the amount of homoplasy. In other words, under this criterion, the shortest possible tree that explains the data is considered best. Some of the basic ideas behind maximum parsimony were presented by James S. Farris in 1970 and Walter M. Fitch in 1971.

In phylogenetics, long branch attraction (LBA) is a form of systematic error whereby distantly related lineages are incorrectly inferred to be closely related. LBA arises when the amount of molecular or morphological change accumulated within a lineage is sufficient to cause that lineage to appear similar to another long-branched lineage, solely because they have both undergone a large amount of change, rather than because they are related by descent. Such bias is more common when the overall divergence of some taxa results in long branches within a phylogeny. Long branches are often attracted to the base of a phylogenetic tree, because the lineage included to represent an outgroup is often also long-branched. The frequency of true LBA is unclear and often debated, and some authors view it as untestable and therefore irrelevant to empirical phylogenetic inference. Although often viewed as a failing of parsimony-based methodology, LBA could in principle result from a variety of scenarios and be inferred under multiple analytical paradigms.

In phylogenetics, a primitive character, trait, or feature of a lineage or taxon is one that is inherited from the common ancestor of a clade and has undergone little change since. Conversely, a trait that appears within the clade group is called advanced or derived. A clade is a group of organisms that consists of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants.

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy is an ancestral character state. A symplesiomorphy is a plesiomorphy shared by two or more taxa. Pseudoplesiomorphy is any trait that can neither be identified as a plesiomorphy nor as an apomorphy.

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to the focal taxon. It can therefore be considered an apomorphy in relation to a single taxon. The word autapomorphy, first introduced in 1950 by German entomologist Willi Hennig, is derived from the Greek words αὐτός, aut- = "self"; ἀπό, apo = "away from"; and μορφή, morphḗ = "shape".

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional approach, in which taxon names are defined by a type, which can be a specimen or a taxon of lower rank, and a description in words. Phylogenetic nomenclature is currently regulated by the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode).

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to evolution:

Character evolution is the process by which a character or trait evolves along the branches of an evolutionary tree. Character evolution usually refers to single changes within a lineage that make this lineage unique from others. These changes are called character state changes and they are often used in the study of evolution to provide a record of common ancestry. Character state changes can be phenotypic changes, nucleotide substitutions, or amino acid substitutions. These small changes in a species can be identifying features of when exactly a new lineage diverged from an old one.

Homoplasy, in biology and phylogenetics, is when a trait has been gained or lost independently in separate lineages over the course of evolution. This is different from homology, which is when the similarity of traits can be parsimoniously explained by common ancestry. Homoplasy can arise from both similar selection pressures acting on adapting species, and the effects of genetic drift.

This glossary of evolutionary biology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in the study of evolutionary biology, population biology, speciation, and phylogenetics, as well as sub-disciplines and related fields. For additional terms from related glossaries, see Glossary of genetics, Glossary of ecology, and Glossary of biology.