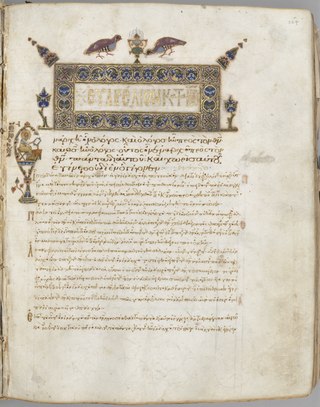

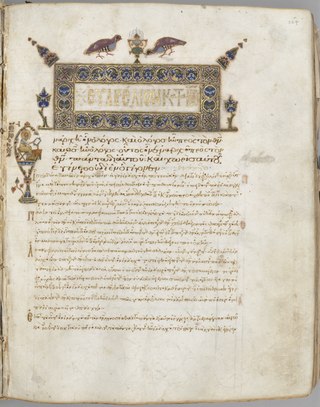

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Illuminated manuscripts include liturgical books such as psalters, courtly literature, and documents such as proclamations.

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127. It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas. Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

The Artuqid dynasty was established in 1102 as a Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. It formed a Turkoman dynasty rooted in the Oghuz Döğer tribe, and followed the Sunni Muslim faith. It ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz Turks and ruled one of the Turkmen beyliks of the Seljuk Empire. Artuk's sons and descendants ruled the three branches in the region: Sökmen's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Ilghazi's branch ruled from Mardin and Mayyafariqin between 1106 and 1186 and Aleppo from 1117–1128; and the Harput line starting in 1112 under the Sökmen branch, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the region has been known by the traditional Arabic name of al-Jazira and the Syriac variant Gāzartā or Gozarto (ܓܙܪܬܐ). The Euphrates and Tigris rivers transform Mesopotamia into almost an island, as they are joined together at the Shatt al-Arab in the Basra Governorate of Iraq, and their sources in eastern Turkey are in close proximity.

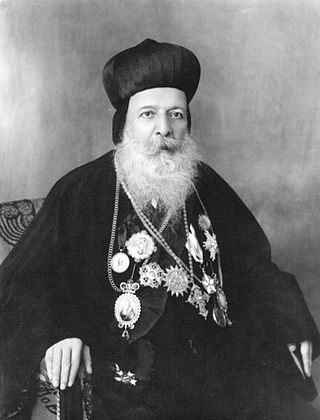

The Maphrian, originally known as the Grand Metropolitan of the East and also known as the Catholicos, was the second-highest rank in the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Syriac Orthodox Church, right below that of patriarch. The office of a maphrian is an maphrianate. There have been three maphrianates in the history of the Syriac Orthodox Church and one, briefly, in the Syriac Catholic Church.

Dayro d-Mor Mattai is a Syriac Orthodox Church monastery on Mount Alfaf in northern Iraq, 20 kilometers northeast of the city of Mosul. It is recognized as one of the oldest Christian monasteries in existence.

Bartella is a town that is located in the Nineveh Plains in northern Iraq, about 21 kilometres east of Mosul.

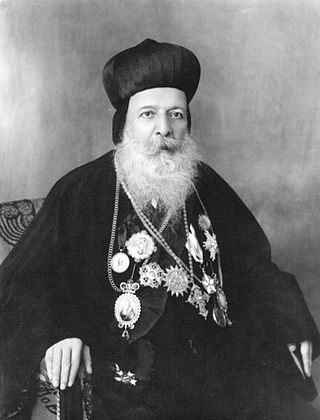

Ignatius Aphrem I Barsoum was the 120th Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1933 until his death in 1957. He was consecrated as a Metropolitan and as a Patriarch at a very hard time for the Syriac Orthodox church and its people and parishes and he worked very hard to re-establish the church initiations to where his people moved. He researched, wrote, translated, scriped, and published many scholarly works that included books on the saints, tradition, liturgy, music, and history of Syriac Orthodox Church.

The Seljuk Empire, or the GreatSeljuk Empire, was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, established and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of 3.9 million square kilometres from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south.

Ignatius III David was the Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1222 until 1252.

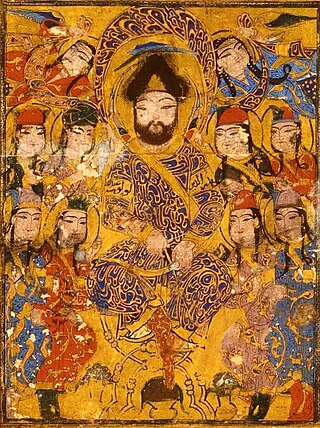

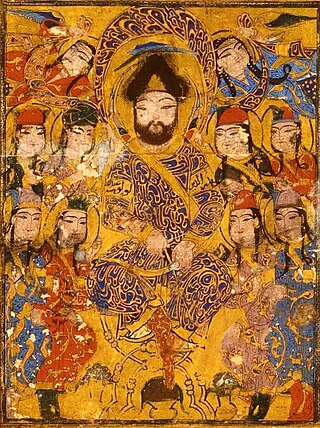

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552 were metropolitan provinces and dioceses of the Church of the East, during the period from 1318 to 1552. They were far fewer in number than during the period of the Church's greatest expansion in the tenth century. Between 1318 and 1552, the geographical horizons of the Church of the East, which had once stretched from Egypt to China, narrowed drastically. By 1552, with the exception of a number of East Syriac communities in India, the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Church of the East was confined to its original heartland in northern Mesopotamia.

In the period of its greatest expansion, in the tenth century, the Syriac Orthodox Church had around 20 metropolitan dioceses and a little over a hundred suffragan dioceses. By the seventeenth century, only 20 dioceses remained, reduced in the twentieth century to 10. The seat of Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch was at Mardin before the First World War, and thereafter in Deir Zaʿfaran, from 1932 in Homs, and finally from 1959 in Damascus.

Mar Denha II was patriarch of the Church of the East from 1336/7 to 1381/2. Although no history of his reign has survived, references in a number of Nestorian, Jacobite and Moslem sources provide some details of his patriarchate.

Monastery of the Martyrs Mar Behnam and Marth Sarah, is a Syriac Catholic monastery in northern Iraq in the village Khidr Ilyas close to the town of Beth Khdeda. The tomb of Mar Benham was heavily damaged on March 19, 2015, by the Islamic State, and the exterior murals were desecrated in all of the monastery's buildings. Repair work restoring the monastery and the tomb of Mar Behnam to its pre-ISIS condition was completed by early December 2018.

Gumal was a diocese of the Syriac Orthodox Church. Bishops of Gumal are attested between the sixth and tenth centuries, but the diocese may have persisted into the thirteenth century.

John XII Yeshu was the Patriarch of Antioch, and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1208 until his death in 1220.

John IV Sarugoyo was the Maphrian of the East of the Syriac Orthodox Church, from 1164 until his death in 1189.

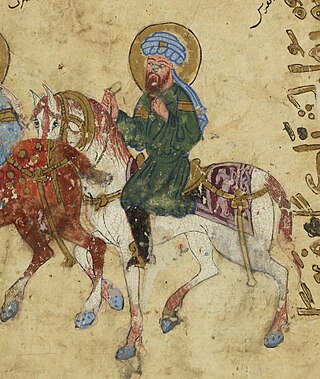

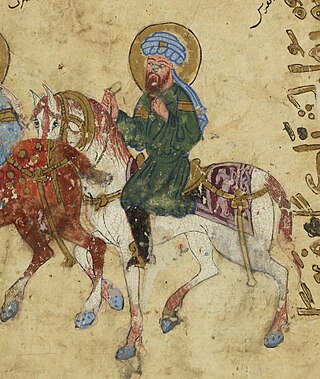

The Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī is a collection of fifty tales or maqāmāt written at the end of the 11th or the beginning of the 12th century by al-Ḥarīrī of Basra (1054–1122), a poet and government official of the Seljuk Empire. The text presents a series of tales regarding the adventures of the fictional character Abū Zayd of Saruj who travels and deceives those around him with his skill in the Arabic language to earn rewards. Although probably less creative than the work of its precursor, Maqāmāt al-Hamadhānī, the Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī became extremely popular, with reports of seven hundred copies authorized by al-Ḥarīrī during his lifetime.

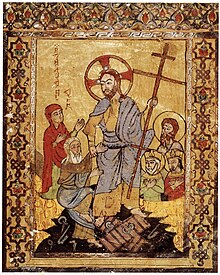

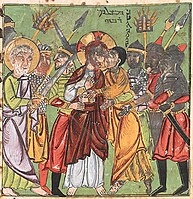

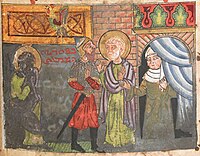

Vatican Library, Syr. 7170 is a Syriac manuscript dated to circa 1220 CE. This is one of the few highly illustrated Middle-Eastern Christian manuscripts from the 13th century.