Related Research Articles

Dalai Lama is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and incumbent Dalai Lama is Tenzin Gyatso, who lives in exile as a refugee in India. The Dalai Lama is also considered to be the successor in a line of tulkus who are believed to be incarnations of Avalokiteśvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate or Junggar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from the Great Wall of China in the east to present-day Kazakhstan in the west. The core of the Dzungar Khanate is today part of northern Xinjiang, also called Dzungaria.

While the Tibetan plateau has been inhabited since pre-historic times, most of Tibet's history went unrecorded until the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism around the 6th century. Tibetan texts refer to the kingdom of Zhangzhung as the precursor of later Tibetan kingdoms and the originators of the Bon religion. While mythical accounts of early rulers of the Yarlung Dynasty exist, historical accounts begin with the introduction of Buddhism from Nepal in the 6th century and the appearance of envoys from the unified Tibetan Empire in the 7th century. Following the dissolution of the empire and a period of fragmentation in the 9th-10th centuries, a Buddhist revival in the 10th–12th centuries saw the development of three of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Tsangyang Gyatso was the 6th Dalai Lama. He was an unconventional Dalai Lama that preferred a libertine lifestyle to that of an ordained monk. His regent was killed before he was kidnapped by Lha-bzang Khan of the Khoshut Khanate and disappeared.

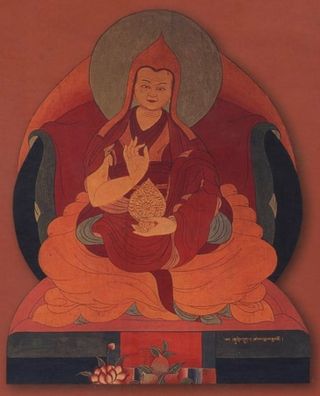

Kelzang Gyatso, also spelled Kalzang Gyatso, Kelsang Gyatso and Kezang Gyatso, was the 7th Dalai Lama of Tibet, recognized as the true incarnation of the 6th Dalai Lama, and enthroned after a pretender was deposed.

Erdeniin Galdan, known as Galdan Boshugtu Khan was a Choros Dzungar-Oirat khan of the Dzungar Khanate. As fourth son of Erdeni Batur, founder of the Dzungar Khanate, Galdan was a descendant of Esen Taishi, the powerful Oirat Khan of the Northern Yuan dynasty who united all Mongols in the 15th century. Galdan's mother Yum Aga was a daughter of Güshi Khan, the first Khoshut-Oirat King of Tibet.

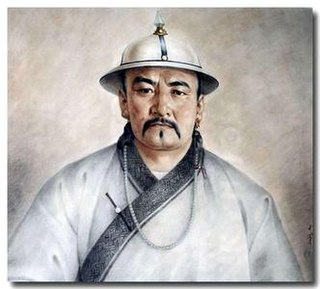

Lha-bzang Khan was the ruler of the Khoshut tribe of the Oirats. He was the son of Tenzin Dalai Khan (1668–1701) and grandson of Güshi Khan, being the last khan of the Khoshut Khanate and Oirat King of Tibet. He acquired effective power as ruler of Tibet by eliminating the regent (desi) Sangye Gyatso and the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, but his rule was cut short by an invasion by another group of Oirats, the Dzungar people. At length, this led to the direct involvement of the Chinese Qing dynasty in the Tibetan politics.

Tsewang Rabtan was a Choros (Oirats) prince and the Khong Tayiji of the Dzungar Khanate from 1697 until his death in 1727. He was married to Lha-bzang Khan's sister.

Yeshe Gyatso (1686–1725) was a pretender for the position of the 6th Dalai Lama of Tibet. Declared by Lha-bzang Khan of the Khoshut Khanate on June 28, 1707, he was the only unofficial Dalai Lama. While praised for his personal moral qualities, he was not recognized by the bulk of the Tibetans and Mongols and is not counted in the official list of the Dalai Lamas.

There were several Mongol invasions of Tibet. The earliest is the alleged plot to invade Tibet by Genghis Khan in 1206, which is considered anachronistic; there is no evidence of Mongol-Tibetan encounters prior to the military campaign in 1240. The first confirmed campaign is the invasion of Tibet by the Mongol general Doorda Darkhan in 1240, a campaign of 30,000 troops that resulted in 500 casualties. The campaign was smaller than the full-scale invasions used by the Mongols against large empires. The purpose of this attack is unclear, and is still in debate among Tibetologists. Then in the late 1240s Mongol prince Godan invited Sakya lama Sakya Pandita, who urged other leading Tibetan figures to submit to Mongol authority. This is generally considered to have marked the beginning of Mongol rule over Tibet, as well as the establishment of patron and priest relationship between Mongols and Tibetans. These relations were continued by Kublai Khan, who founded the Mongol Yuan dynasty and granted authority over whole Tibet to Drogon Chogyal Phagpa, nephew of Sakya Pandita. The Sakya-Mongol administrative system and Yuan administrative rule over the region lasted until the mid-14th century, when the Yuan dynasty began to crumble.

The Lhasa riot of 1750 or Lhasa uprising of 1750 took place in the Tibetan capital Lhasa, and lasted several days during the period of the Qing dynasty's patronage in Tibet. The uprising began on 11 November 1750 after the expected new regent of Tibet, Gyurme Namgyal, was assassinated by two Qing Manchu diplomats, or ambans. As a result, both ambans were murdered, and 51 Qing soldiers and 77 Chinese citizens were killed in the uprising. A year later the leader of the rebellion, Lobsang Trashi, and fourteen other rebels were executed by Qing officials.

The Khoshut Khanate was a Mongol Oirat khanate based in the Tibetan Plateau from 1642 to 1717. Based in modern Qinghai, it was founded by Güshi Khan in 1642 after defeating the opponents of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. The 5th Dalai Lama established a civil administration known as Ganden Phodrang with the aid of Güshi Khan. The role of the khanate in the affairs of Tibet has been subject to various interpretations. Some sources claim that the Khoshut did not interfere in Tibetan affairs and had a priest and patron relationship between the khan and Dalai Lama while others claim that Güshi appointed a minister, Sonam Rapten, as de facto administrator of civil affairs while the Dalai Lama was only responsible for religious matters. In the last years of the khanate, Lha-bzang Khan murdered the Tibetan regent and deposed the 6th Dalai Lama in favor of a pretender Dalai Lama.

The Battle of the Salween River was fought in September 1718 close to the Nagqu in Tibet, between an expedition of the Qing dynasty to Lhasa and a Dzungar Khanate force that blocked its path.

Buddhists, predominantly from India, first actively disseminated their practices in Tibet from the 6th to the 9th centuries CE. During the Era of Fragmentation, Buddhism waned in Tibet, only to rise again in the 11th century. With the Mongol invasion of Tibet and the establishment of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in China, Tibetan Buddhism spread beyond Tibet to Mongolia and China. From the 14th to the 20th centuries, Tibetan Buddhism was patronized by the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Manchurian Qing dynasty (1644–1912) which ruled China.

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642, after the Oirat lord Güshi Khan who founded the Khoshut Khanate conferred all temporal power on the 5th Dalai Lama in a ceremony in Shigatse in the same year. Lhasa again became the capital of Tibet, and the Ganden Phodrang operated until the 1950s. The Ganden Phodrang accepted China's Qing emperors as overlords after the 1720 expedition, and the Qing became increasingly active in governing Tibet starting in the early 18th century. After the fall of the Qing empire in 1912, the Ganden Phodrang government lasted until the 1950s, when Tibet was annexed by the People's Republic of China. During most of the time from the early Qing period until the end of Ganden Phodrang rule, a governing council known as the Kashag operated as the highest authority in the Ganden Phodrang administration.

Polhané Sönam Topgyé was one of the most important political personalities of Tibet in the first half of the 18th century. Between 1728 and 1747 he was effectively the ruling prince of Tibet and carried royal titles during the period of Qing rule of Tibet. He is known as an excellent administrator, a fearsome warrior and a grand strategist. After the troubled years under the reign of Lhazang Khan, the bloody invasion of Tsering Dhondup and the civil war, his government ushered in a relatively long period of stability and internal and external peace for Tibet.

Gyurme Namgyal was a ruling prince of Tibet of the Pholha family. He was the son and successor of Polhané Sönam Topgyé and ruled from 1747 to 1750 during the period of Qing rule of Tibet. Gyurme Namgyal was murdered by the Manchu Ambans Fucin and Labdon in 1750. He was the last dynastic ruler of Tibet. After his death, in 1751, the Tibetan Ganden Phodrang government was taken over by the 7th Dalai Lama, Kelzang Gyatso. Thus began a new administrative order that would last for the next 150 years.

Khangchenné Sonam Gyalpo was the first important representative of the noble house Gashi in Tibet. Between 1721 and 1727 he led the Tibetan cabinet that governed the country during the period of Qing rule of Tibet. He was eventually murdered by his peers in the cabinet, which triggered a bloody but brief civil war. The nobleman Polhané Sönam Topgyé came out as the victor and became the new ruling prince of Tibet under the Chinese protectorate.

Tibet under Qing rule refers to the Qing dynasty's rule over Tibet from 1720 to 1912. The Qing rulers incorporated Tibet into the empire along with other Inner Asia territories, although the actual extent of the Qing dynasty's control over Tibet during this period has been the subject of political debate. The Qing called Tibet a fanbu, fanbang or fanshu, which has usually been translated as "vassal", "vassal state", or "borderlands", along with areas like Xinjiang and Mongolia. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control over Tibet, while granting it a degree of political autonomy.

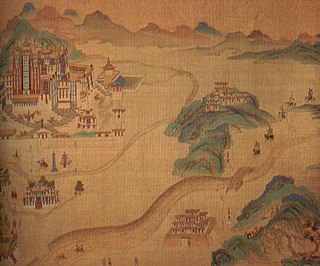

The 1720 Chinese expedition to Tibet or the Chinese conquest of Tibet in 1720 was a military expedition sent by the Qing dynasty to expel the invading forces of the Dzungar Khanate from Tibet and establish Qing rule over the region, which lasted until the empire's fall in 1912.

References

- ↑ Van Schaik 2011, pp. 137-9

- ↑ Van Schaik 2011, pp. 138-9; Petech 1950, pp. 25-41.

- ↑ Van Schaik 2011, pp. 138-9

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 43.

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 40.

- ↑ Shakabpa 2010, p. 435.

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 44.

- ↑ Van Schaik 2011, p. 139.

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 48.

- ↑ Petech 1950, pp. 50-1.

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 62.

- ↑ Petech 1950, p. 61.

- ↑ Petech 1950, pp. 63-4.