The Industrial Revolution, also known as the First Industrial Revolution, was a period of global transition of human economy towards more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes that succeeded the Agricultural Revolution, starting from Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines; new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes; the increasing use of water power and steam power; the development of machine tools; and the rise of the mechanized factory system. Output greatly increased, and the result was an unprecedented rise in population and the rate of population growth. The textile industry was the first to use modern production methods, and textiles became the dominant industry in terms of employment, value of output, and capital invested.

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch production, it is one of the three main production methods.

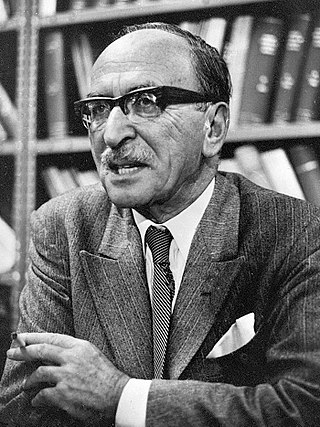

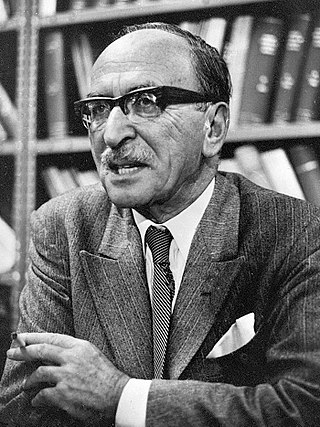

Dennis Gabor was a Hungarian-British electrical engineer and physicist, most notable for inventing holography, for which he later received the 1971 Nobel Prize in Physics. He obtained British citizenship in 1934, and spent most of his life in England.

Sociotechnical systems (STS) in organizational development is an approach to complex organizational work design that recognizes the interaction between people and technology in workplaces. The term also refers to coherent systems of human relations, technical objects, and cybernetic processes that inhere to large, complex infrastructures. Social society, and its constituent substructures, qualify as complex sociotechnical systems.

Lewis Mumford was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a writer. He made signal contributions to social philosophy, American literary and cultural history, and the history of technology.

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The First Industrial Revolution, which ended in the middle of the 19th century, was punctuated by a slowdown in important inventions before the Second Industrial Revolution in 1870. Though a number of its events can be traced to earlier innovations in manufacturing, such as the establishment of a machine tool industry, the development of methods for manufacturing interchangeable parts, as well as the invention of the Bessemer process and Open hearth furnace to produce steel, the Second Industrial Revolution is generally dated between 1870 and 1914.

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques and is one of the categories of world history. Technology can refer to methods ranging from as simple as stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and information technology that has emerged since the 1980s. The term technology comes from the Greek word techne, meaning art and craft, and the word logos, meaning word and speech. It was first used to describe applied arts, but it is now used to describe advancements and changes which affect the environment around us.

The water frame is a spinning frame that is powered by a water-wheel.

In sociology and anthropology, time discipline is the general name given to social and economic rules, conventions, customs, and expectations governing the measurement of time, the social currency and awareness of time measurements, and people's expectations concerning the observance of these customs by others.

Lynn Townsend White Jr. was an American historian. He was a professor of medieval history at Princeton from 1933 to 1937, and at Stanford from 1937 to 1943. He was president of Mills College, Oakland, from 1943 to 1958 and a professor at University of California, Los Angeles from 1958 until 1987. Lynn White helped to found the Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) and was president from 1960 to 1962. He won the Pfizer Award for "Medieval Technology and Social Change" from the History of Science Society (HSS) and the Leonardo da Vinci medal and Dexter prize from SHOT in 1964 and 1970. He was president of the History of Science Society from 1971 to 1972. He was president of The Medieval Academy of America from 1972–1973, and the American Historical Association in 1973.

Enid Mumford was a British social scientist, computer scientist and Professor Emerita of Manchester University and a visiting fellow at Manchester Business School, largely known for her work on human factors and socio-technical systems.

During its 600-year existence, the Ottoman Empire made significant advances in science and technology, in a wide range of fields including mathematics, astronomy and medicine.

Ancient Chinese scientists and engineers made significant scientific innovations, findings and technological advances across various scientific disciplines including the natural sciences, engineering, medicine, military technology, mathematics, geology and astronomy.

Criticism of technology is an analysis of adverse impacts of industrial and digital technologies. It is argued that, in all advanced industrial societies, technology becomes a means of domination, control, and exploitation, or more generally something which threatens the survival of humanity. Some of the technology opposed by the most radical critics may include everyday household products, such as refrigerators, computers, and medication. However, criticism of technology comes in many shades.

Monopolies of knowledge arise when the ruling class maintains political power through control of key communications technologies. The Canadian economic historian Harold Innis developed the concept of monopolies of knowledge in his later writings on communications theories.

Science and Civilisation in China (1954–present) is an ongoing series of books about the history of science and technology in China published by Cambridge University Press. It was initiated and edited by British historian Joseph Needham (1900–1995). Needham was a well-respected scientist before undertaking this encyclopedia and was even responsible for the "S" in UNESCO. To date there have been seven volumes in twenty-seven books. The series was on the Modern Library Board's 100 Best Nonfiction books of the 20th century. Needham's work was the first of its kind to praise Chinese scientific contributions and provide their history and connection to global knowledge in contrast to eurocentric historiography.

The Myth of the Machine is a two-volume book by Lewis Mumford that takes an in-depth look at the forces that have shaped modern technology since prehistoric times. The first volume, Technics and Human Development, was published in 1967, followed by the second volume, The Pentagon of Power, in 1970. Mumford shows the parallel developments between human tools and social organization mainly through language and rituals. It is considered a synthesis of many theories Mumford developed throughout his prolific writing career. Volume 2 was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection.

The concept of engineering has existed since ancient times as humans devised fundamental inventions such as the pulley, lever, and wheel. Each of these inventions is consistent with the modern definition of engineering, exploiting basic mechanical principles to develop useful tools and objects.

Technology, society and life or technology and culture refers to the inter-dependency, co-dependence, co-influence, and co-production of technology and society upon one another. Evidence for this synergy has been found since humanity first started using simple tools. The inter-relationship has continued as modern technologies such as the printing press and computers have helped shape society. The first scientific approach to this relationship occurred with the development of tektology, the "science of organization", in early twentieth century Imperial Russia. In modern academia, the interdisciplinary study of the mutual impacts of science, technology, and society, is called science and technology studies.

Sociotechnology is the study of processes on the intersection of society and technology. Vojinović and Abbott define it as "the study of processes in which the social and the technical are indivisibly combined". Sociotechnology is an important part of socio-technical design, which is defined as "designing things that participate in complex systems that have both social and technical aspects".