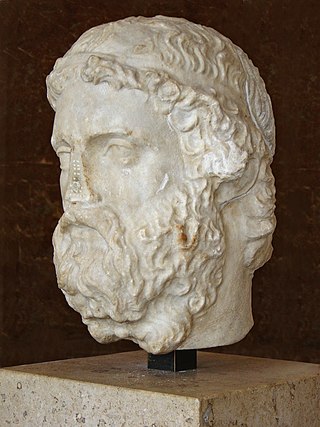

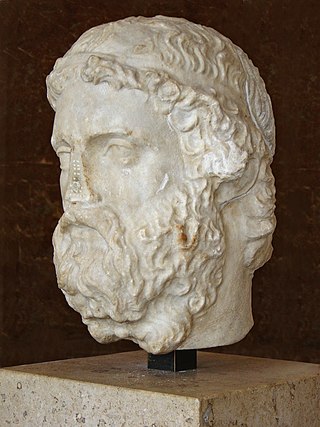

Hesiod was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.

Sappho was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sappho was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets and was given names such as the "Tenth Muse" and "The Poetess". Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and what is extant has mostly survived in fragmentary form; only the Ode to Aphrodite is certainly complete. As well as lyric poetry, ancient commentators claimed that Sappho wrote elegiac and iambic poetry. Three epigrams formerly attributed to Sappho are extant, but these are actually Hellenistic imitations of Sappho's style.

Bacchylides was a Greek lyric poet. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets, which included his uncle Simonides. The elegance and polished style of his lyrics have been noted in Bacchylidean scholarship since at least Longinus. Some scholars have characterized these qualities as superficial charm. He has often been compared unfavourably with his contemporary, Pindar, as "a kind of Boccherini to Pindar's Haydn". However, the differences in their styles do not allow for easy comparison, and translator Robert Fagles has written that "to blame Bacchylides for not being Pindar is as childish a judgement as to condemn ... Marvell for missing the grandeur of Milton". His career coincided with the ascendency of dramatic styles of poetry, as embodied in the works of Aeschylus or Sophocles, and he is in fact considered one of the last poets of major significance within the more ancient tradition of purely lyric poetry. The most notable features of his lyrics are their clarity in expression and simplicity of thought, making them an ideal introduction to the study of Greek lyric poetry in general and to Pindar's verse in particular.

Archilochus was a Greek lyric poet of the Archaic period from the island of Paros. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the earliest known Greek author to compose almost entirely on the theme of his own emotions and experiences.

Alcman was an Ancient Greek choral lyric poet from Sparta. He is the earliest representative of the Alexandrian canon of the Nine Lyric Poets. He wrote six books of choral poetry, most of which is now lost; his poetry survives in quotation from other ancient authors and on fragmentary papyri discovered in Egypt. His poetry was composed in the local Doric dialect with Homeric influences. Based on his surviving fragments, his poetry was mostly hymns, and seems to have been composed in long stanzas made up of lines in several different meters.

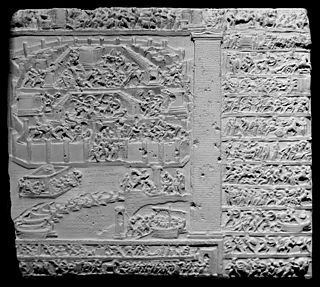

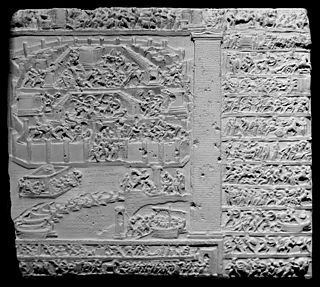

In Greek mythology, Adrastus or Adrestus, , was a king of Argos, and leader of the Seven against Thebes. He was the son of the Argive king Talaus, but was forced out of Argos by his dynastic rival Amphiaraus. He fled to Sicyon, where he became king. Later he reconciled with Amphiaraus and returned to Argos as its king.

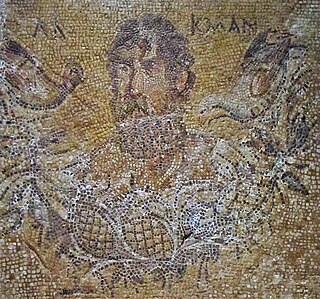

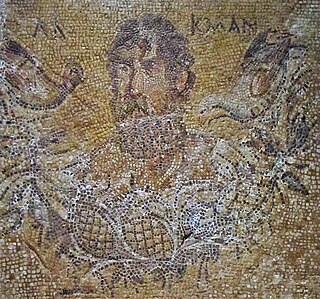

In Greek mythology, Geryon, son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe, the grandson of Medusa and the nephew of Pegasus, was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides in the far west of the Mediterranean. A more literal-minded later generation of Greeks associated the region with Tartessos in southern Iberia. Geryon was often described as a monster with either three bodies and three heads, or three heads and one body, or three bodies and one head. He is commonly accepted as being mostly humanoid, with some distinguishing features and in mythology, famed for his cattle.

In Greek mythology, Peitho is the personification of persuasion. She is typically presented as an important companion of Aphrodite. Her opposite is Bia, the personification of force. As a personification, she was sometimes imagined as a goddess and sometimes an abstract power with her name used both as a common and proper noun. There is evidence that Peitho was referred to as a goddess before she was referred to as an abstract concept, which is rare for a personification. Peitho represents both sexual and political persuasion. She is associated with the art of rhetoric.

Mimnermus was a Greek elegiac poet from either Colophon or Smyrna in Ionia, who flourished about 632–629 BC. He was strongly influenced by Homer, yet he wrote short poems suitable for performance at drinking parties and was remembered by ancient authorities chiefly as a love poet. Mimnermus in turn exerted a strong influence on Hellenistic poets such as Callimachus and thus also on Roman poets such as Propertius, who even preferred him to Homer for his eloquence on love themes.

Anyte of Tegea was a Hellenistic poet from Tegea in Arcadia. Little is known of her life, but twenty-four epigrams attributed to her are preserved in the Greek Anthology, and one is quoted by Julius Pollux; nineteen of these are generally accepted as authentic. She introduced rural themes to the genre, which became a standard theme in Hellenistic epigrams. She is one of the nine outstanding ancient women poets listed by Antipater of Thessalonica in the Palatine Anthology. Her pastoral poetry may have influenced Theocritus, and her works were adapted by several later poets, including Ovid.

Corinna or Korinna was an ancient Greek lyric poet from Tanagra in Boeotia. Although ancient sources portray her as a contemporary of Pindar, not all modern scholars accept the accuracy of this tradition. When she lived has been the subject of much debate since the early twentieth century, proposed dates ranging from the beginning of the fifth century to the late third century BC.

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic period, are the two epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, set in an idealized archaic past today identified as having some relation to the Mycenaean era. These two epics, along with the Homeric Hymns and the two poems of Hesiod, the Theogony and Works and Days, constituted the major foundations of the Greek literary tradition that would continue into the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods.

Anacreon was a Greek lyric poet, notable for his drinking songs and erotic poems. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets. Anacreon wrote all of his poetry in the ancient Ionic dialect. Like all early lyric poetry, it was composed to be sung or recited to the accompaniment of music, usually the lyre. Anacreon's poetry touched on universal themes of love, infatuation, disappointment, revelry, parties, festivals, and the observations of everyday people and life.

Praxilla, was a Greek lyric poet of the 5th century BC from Sicyon on the Gulf of Corinth. Five quotations attributed to Praxilla and three paraphrases from her poems survive. The surviving fragments attributed to her come from both religious choral lyric and drinking songs (skolia); the three paraphrases are all versions of myths. Various social contexts have been suggested for Praxilla based on this range of surviving works. These include that her poetry was in fact composed by two different authors, that Praxilla was a hetaira (courtesan), that she was a professional musician, or that the drinking songs derive from a non-elite literary tradition rather than being authored by a single writer.

Stesichorus was a Greek lyric poet native of Metauros. He is best known for telling epic stories in lyric metres, and for some ancient traditions about his life, such as his opposition to the tyrant Phalaris, and the blindness he is said to have incurred and cured by composing verses first insulting and then flattering to Helen of Troy.

Erinna was an ancient Greek poet. She is best known for her long poem The Distaff, a 300-line hexameter lament for her childhood friend Baucis, who had died shortly after her marriage. A large fragment of this poem was discovered in 1928 at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. Along with The Distaff, three epigrams ascribed to Erinna are known, preserved in the Greek Anthology. Biographical details about Erinna's life are uncertain. She is generally thought to have lived in the first half of the fourth century BC, though some ancient traditions have her as a contemporary of Sappho; Telos is generally considered to be her most likely birthplace, but Tenos, Teos, Rhodes, and Lesbos are all also mentioned by ancient sources as her home.

Nossis was a Hellenistic poet from Epizephyrian Locris in Magna Graecia. Probably well-educated and from a noble family, Nossis was influenced by and claimed to rival Sappho. Eleven or twelve of her epigrams, mostly religious dedications and epitaphs, survive in the Greek Anthology, making her one of the best-preserved ancient Greek women poets, though her work does not seem to have entered the Greek literary canon. In the twentieth century, the imagist poet H. D. was influenced by Nossis, as was Renée Vivien in her French translation of the ancient Greek women poets.

The epinikion or epinicion is a genre of occasional poetry also known in English as a victory ode. In ancient Greece, the epinikion most often took the form of a choral lyric, commissioned for and performed at the celebration of an athletic victory in the Panhellenic Games and sometimes in honor of a victory in war. Major poets in the genre are Simonides, Bacchylides, and Pindar.

Myrtis was an ancient Greek poet from Anthedon, a town in Boeotia. She was said to have taught the poets Pindar and Corinna. The only surviving record of her poetry is a paraphrase by Plutarch, discussing a local Boeotian legend. In antiquity she was included by Antipater of Thessalonica in his canon of nine female poets, and a bronze statue of her was reportedly made by Boïscus. In the modern world, Myrtis has been represented in artworks by Judy Chicago and Anselm Kiefer, and a poem by Michael Longley.

Melinno was a Greek lyric poet. She is known from a single surviving poem, known as the "Ode to Rome". The poem survives in a quotation by the fifth century AD author Stobaeus, who included it in a compilation of poems on manliness. It was apparently included in this collection by mistake, as Stobaeus misinterpreted the word ρώμα in the first line as meaning "strength", rather than being the Greek name for the city of Rome.