View of Tell Leilan | |

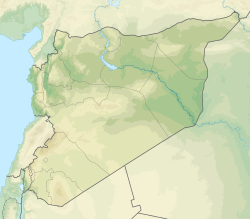

| Location | Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°57′26″N41°30′19″E / 36.95722°N 41.50528°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 5000 BC |

| Abandoned | 1726 BC |

| Cultures | Akkadian, Assyrian |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Tell Leilan is an archaeological site situated near the Wadi Jarrah in the Khabur River basin in Al-Hasakah Governorate, northeastern Syria. The site has been occupied since the 5th millennium BC. During the late third millennium, the site was known as Shekhna. During that time it was under control of the Akkadian Empire and was used as an administrative center. [1] [2] Around 1800 BC, the site was renamed "Šubat-Enlil" by the king Shamshi-Adad I, and it became his residential capital. [3] Shubat-Enlil was abandoned around 1700 BC.