Related Research Articles

Av is the eleventh month of the civil year and the fifth month of the ecclesiastical year on the Hebrew calendar. It is a month of 30 days, and usually occurs in July–August on the Gregorian calendar.

Elephantine is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological digs on the island became a World Heritage Site in 1979, along with other examples of Upper Egyptian architecture, as part of the "Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae".

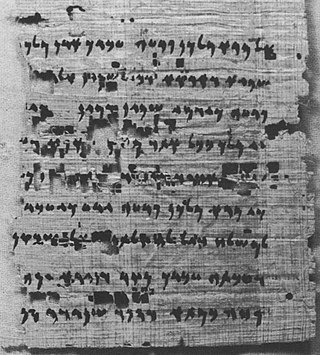

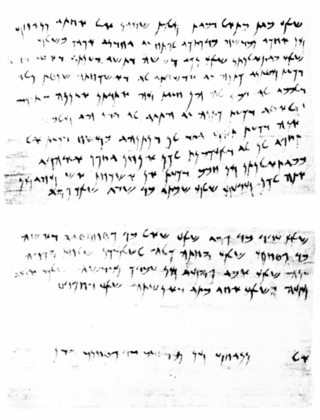

The Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of papyri and ostraca in hieratic and demotic Egyptian, Aramaic, Koine Greek, Latin and Coptic, spanning a period of 100 years in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE. The documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives and are thus an invaluable source of knowledge for scholars of varied disciplines such as epistolography, law, society, religion, language, and onomastics. The Elephantine documents include letters and legal contracts from family and other archives: divorce documents, the manumission of enslaved people, and other business. The dry soil of Upper Egypt preserved the documents.

Bethel, meaning 'House of El' or 'House of God' in Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic, was the name of a god or an aspect of a god in some ancient Middle Eastern texts dating to the Assyrian, Achaemenid, and Hellenistic periods. The term appears in the Torah and the Christian Bible, but opinions differ as to whether those references are to a god or to a place.

The Caspians were an Iranic people of antiquity who dwelt along the southwestern shores of the Caspian Sea, in the region known as Caspiane. Caspian is the English version of the Greek ethnonym Kaspioi, mentioned twice by Herodotus among the Achaemenid satrapies of Darius the Great and applied by Strabo. The name is attested in Old Iranian.

Imperial Aramaic is a linguistic term, coined by modern scholars in order to designate a specific historical variety of Aramaic language. The term is polysemic, with two distinctive meanings, wider (sociolinguistic) and narrower (dialectological). Since most surviving examples of the language have been found in Egypt, the language is also referred to as Egyptian Aramaic.

Old Aramaic refers to the earliest stage of the Aramaic language, known from the Aramaic inscriptions discovered since the 19th century.

The Story of Aḥiqar, also known as the Words of Aḥiqar, is a story first attested to in Imperial Aramaic from the fifth century BCE on papyri from Elephantine, Egypt, that circulated widely in the Middle and the Near East. It has been characterised as "one of the earliest 'international books' of world literature".

Georges Émile Goyon was a French Egyptologist. A senior fellow at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), he was King Farouk's private archaeologist.

Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften, or KAI, is the standard source for the original text of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions not contained in the Hebrew Bible.

Mibtahiah , was a Jewish businesswoman and banker. She belonged to the first Jewish women of which there is any information outside of the Bible, as well as the first of Jewish businesswomen. She is well-documented from the Ancient Aramaic papyrus collections from Elephantine in Egypt, known as the Mond-Cecil papyri in the Cairo Museum and the Bodleian papyri, which is also named the Mibtahiah archive after her.

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the societies and histories of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.

The Adon Papyrus, also known as the Aramaic Saqqara Papyrus is an Aramaic papyrus found in 1942 at Saqqara. It was first published in 1948 by André Dupont-Sommer.

The Hermopolis Aramaic papyri are a group of eight Aramaic papyri thought to be from the late sixth or early fifth century BCE, found in 1945 at Hermopolis. They were first published in 1966 by Edda Bresciani and Cairo University's Murad Kamil.

The Padua Aramaic papyri are a group of three Aramaic papyri thought to be from the 400s BCE, found in a collection of antiquities in the Italian city of Padua. The papyri are unprovenanced, but are thought to have been from Elephantine, which would make them the first Elephantine papyri and ostraca to have been discovered. They were acquired by Giovanni Belzoni in c.1815, together with a demotic letter; Belzoni presented them to the Musei Civici di Padova in 1819.

The Phoenician papyrus letters are the only two known papyrus letters written in Phoenician, both found in Egypt. The first was discovered in Cairo in 1939, and the second in Saqqara in 1940. Both letters were first published by Noël Aimé-Giron.

Julius Euting was a German Orientalist.

The Blacas papyrus is an Aramaic papyrus, of which two separate fragments survive, found in Saqqara in 1825. It is known as CIS II 145 and TAD C1.2.

The Behistun papyrus, formally known as Berlin Papyrus P. 13447, is an Aramaic-Egyptian fragmentary partial copy of the Behistun inscription, and one of the Elephantine papyri discovered during the German excavations between 1906 and 1908.

Hor son of Punesh is a magician from ancient Egyptian literature.

References

- 1 2 Botta, A.F. (2012). ""Mr. Elephantine" Bezalel Porten". In the Shadow of Bezalel. Aramaic, Biblical, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Bezalel Porten. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Brill. p. xi-xvi. ISBN 978-90-04-24083-4.

- ↑ Pardee, D. (1988). [Review of Aramaic Texts from North Saqqâra with Some Fragments in Phoenician, by J. B. Segal]. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 47(2), 154–156. http://www.jstor.org/stable/544400

- ↑ Porten, B., & Yardeni, A. (1993). Ostracon Clermont-Ganneau 125(?): A Case of Ritual Purity. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 113(3), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/605393

- ↑ Gianto, A. (2000). [Review of Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Newly Copied, Edited and Translated into English. 4: Ostraca and Assorted Inscriptions (Texts and Studies for Students), by B. Porten & A. Yardeni]. Biblica, 81(3), 443–445. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42614297

- ↑ Dion, P.-E. (2000). [Review of Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Newly Copied, Edited and Translated into Hebrew and English, Vol. 4: Ostraca and Assorted Inscriptions, by B. Porten & A. Yardeni]. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 318, 77–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/1357731

- ↑ Cook, Edward (2022). Biblical Aramaic and Related Dialects: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 3-7. ISBN 978-1-108-78788-8.

Imperial Aramaic (IA) [Footnote: Other names: Official Aramaic, Reichsaramäisch. Because many of the surviving texts come from Egypt, some scholars speak of "Egyptian Aramaic."]… As noted, the documentation of IA is significantly greater than that of Old Aramaic; the hot and dry climate of Egypt has been particularly favorable to the preservation of antiquities, including Aramaic texts written on soft media such as papyrus or leather. The primary, although not exclusive, source of our knowledge of Persian-period Aramaic is a large number of papyri discovered on the island of Elephantine… All of the Egyptian Aramaic texts have been collected and reedited in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt… This is now the standard text edition… Outside of Egypt, Aramaic texts written primarily on hard media such as stone or pottery have been discovered, including texts from Palestine, Arabia, Asia Minor, Iraq (Babylon), and Iran (Persepolis). A recent discovery, of uncertain provenance, is a relatively large collection of documents, now in a private collection, consisting mainly of the correspondence of the official Akhvamazda of Bactria dating from 354 to 324 BCE (Nave & Shaked 2012). They are similar in some ways to the Arshama archive published by Driver; the find-spot was no doubt Afghanistan.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Edda Bresciani; Murād Kāmil, 1966, Le lettere aramaiche di Hermopoli, Memorie (Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche)., ser. 8 ;, v. 12, fasc. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Kraeling, Emil G.H. (1953). The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri: New Documents of the Fifth Century B.C. from the Jewish Colony at Elephantine. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-405-00873-3.

- ↑ Bargès, J.J.L. (1862). Papyrus égypto-araméen appartenant au Musée égyptien du Louvre (in French). Duprat.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Driver, G.R.; Mittwoch, E. (1968). Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B.C. Zeller.