Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies is a 1997 transdisciplinary non-fiction book by the American author Jared Diamond. The book attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians, he asserts that these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on societies and cultures and were not inherent in the Eurasian genomes.

Eurocentrism refers to viewing the West as the center of world events or superior to all other cultures. The exact scope of Eurocentrism varies from the entire Western world to just the continent of Europe or even more narrowly, to Western Europe. When the term is applied historically, it may be used in reference to the presentation of the European perspective on history as objective or absolute, or to an apologetic stance toward European colonialism and other forms of imperialism.

Industrialisation (UK) or industrialization (US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for the purpose of manufacturing. Industrialisation is associated with increase of polluting industries heavily dependent on fossil fuels. With the increasing focus on sustainable development and green industrial policy practices, industrialisation increasingly includes technological leapfrogging, with direct investment in more advanced, cleaner technologies.

Human history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They migrated out of Africa during the Last Ice Age and had populated most of the Earth by the end of the Ice Age 12,000 years ago. Soon afterward, the Neolithic Revolution in West Asia brought the first systematic husbandry of plants and animals, and saw many humans transition from a nomadic life to a sedentary existence as farmers in permanent settlements. The growing complexity of human societies necessitated systems of accounting and writing.

Kenneth Pomeranz, FBA is University Professor of History at the University of Chicago. He received his B.A. from Cornell University in 1980, where he was a Telluride Scholar, and his Ph.D. from Yale University in 1988, where he was a student of Jonathan Spence. He then taught at the University of California, Irvine, for more than 20 years. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences in 2006. In 2013–2014 he was the president of the American Historical Association. Pomeranz has been described as a major figure in the California School of economic history.

David Saul Landes was a professor of economics and of history at Harvard University. He is the author of Bankers and Pashas, Revolution in Time, The Unbound Prometheus, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, and Dynasties. Such works have received both praise for detailed retelling of economic history, as well as scorn on charges of Eurocentrism, a charge he openly embraced, arguing that an explanation for an economic miracle that happened originally only in Europe must of necessity be a Eurocentric analysis.

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor is a 1998 book by historian and economist David Landes (1924–2013). He attempted to explain why some countries and regions experienced near miraculous periods of explosive growth while the rest of the world stagnated. The book compared the long-term economic histories of different regions, specifically Europe, United States, Japan, China, the Arab world, and Latin America. In addition to analyzing economic and cliometric figures, he credited intangible assets, such as culture and enterprise, to explain economic success or failure.

Ellen Meiksins Wood was an American-Canadian Marxist historian, and one of the primary developers of the Marxist tendency known as Political Marxism.

The Great Divergence or European miracle is the socioeconomic shift in which the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilizations, eclipsing previously dominant or comparable civilizations from the Middle East and Asia such as Qing China, Mughal India, the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran, and Tokugawa Japan, among others.

Joel Mokyr is a Dutch-born American-Israeli economic historian who has served as a professor of economics and history and as the Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University since 1994. Since 2001, he has also served as the Sackler Professorial Fellow at the Eitan Berglas School of Economics at Tel Aviv University.

The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, written by the political scientist John M. Hobson in 2004, is a book that argues against the historical theory of the rise of the West after 1492 as a "virgin birth", but rather as a product of Western interactions with a more technically and socially advanced Eastern civilization.

James Morris Blaut was an American professor of anthropology and geography at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His studies focused on agricultural microgeography, cultural ecology, theory of nationalism, philosophy of science, historiography and the relations between the First and the Third World. He was a critic of Eurocentrism. Blaut was one of the most widely read authors in the field of geography.

Eric Lionel Jones was a British-Australian economist and historian, known for his 1981 book The European Miracle.

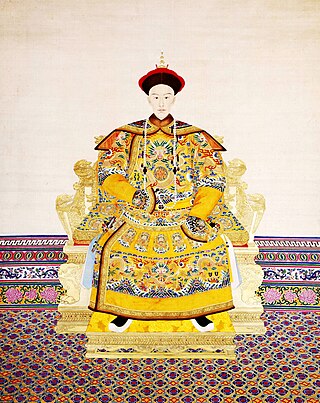

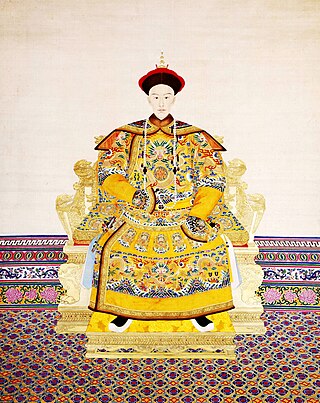

During the Manchu–led Qing dynasty, the economy was significantly developed and markets continued to expand especially in the High Qing era, and imperial China experienced a second commercial revolution in the economic history of China from the mid-16th century to the end of the 18th century. But akin to the other major non-European powers around the world at that time like the Islamic gunpowder empires and Tokugawa Japan, such an economy development did not keep pace with the economies of European countries in the Industrial Revolution occurring by the early 19th century, which resulted in a dramatic change described by the 19th-century Qing official Li Hongzhang as "the biggest change in more than three thousand years" (三千年未有之大變局).

The sprouts of capitalism, seeds of capitalism or capitalist sprouts are features of the economy of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties that mainland Chinese historians have seen as resembling developments in pre-industrial Europe, and as precursors of a hypothetical indigenous development of industrial capitalism. Korean nationalist historiography has also adopted the idea. In China the sprouts theory was denounced during the Cultural Revolution, but saw renewed interest after the economy began to grow rapidly in the 1980s.

Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power is a book of political theory and comparative history by Karl August Wittfogel (1896–1988) published by Yale University Press in 1957. The book offers an explanation for the despotic governments in "Oriental" societies, where control of water was necessary for irrigation and flood-control. Managing these projects required large-scale bureaucracies, which dominated the economy, society, and religious life. This despotism differed from the Western experience, where power was distributed among contending groups. The book argues that this form of "hydraulic despotism" characterized ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, Hellenistic Greece and imperial Rome, the Abbasid Caliphate, imperial China, the Moghul empire, and Incan Peru. Wittfogel further argues that 20th century Marxist-Leninist regimes, such as the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China, though they were not themselves hydraulic societies, did not break away from their historical condition and remained systems of "total power" and "total terror".

The Mughal Empire's economic prowess and sophisticated infrastructure played a pivotal role in shaping the Indian subcontinent's history. While Mughal Empire is conventionally said to have been founded in 1526 by Babur, the Mughal imperial structure, however, is sometimes dated to 1600, to the rule of Babur's grandson, Akbar. The economy in the South Asia during the Mughal Empire era performed just as it did in medieval times, though now it would face the stress of extensive regional tensions. Mughal India's economy has been described as a form of proto-industrialization, an inspiration for 18th-century putting-out system of Western Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution. It was described as large and prosperous. India producing about 28% of the world's industrial output up until the 18th century with significant exports in textiles, shipbuilding, and steel, driving a strong export-driven economy. While at the start of 17th century, the economic expansion within Mughal territories become the largest and surpassed Qing dynasty and Europe. The share of world's economy grew from 22.7% in 1600, which at the end of 16th century, has surpassed China to become the world's largest GDP. Bengal Subah, the empire's wealthiest province alone, the province statistically has contributed to 12% of Gross domestic product and a major hub for industries, contributing significantly to global trade and European imports, particularly in textiles and shipbuilding.

The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy is a 2000 nonfiction book by Kenneth Pomeranz, published by Princeton University Press, on the subject of Great Divergence in the world history.

The California School of economic history is a label that as been applied to a particular approach to the economic history of the early modern world. The chief elements of their analysis is that over the period from 1400 to 1800 the most advanced economies of Eurasia formed a world of surprising resemblances. They argue that the Great Divergence, a divergence between the West and the Rest only really began with industrialisation in the 19th century. This Great Divergence should be interpreted as a more contingent and more recent phenomenon than the proponents of the Great Divergence have argued for. The basic cause of the divergence being framed in terms of the availability of the resources in the context of global interconnections and comparisons. The most noted proponents of the approach include: Kenneth Pomeranz, Roy Bin Wong, Jack Goldstone, James Z. Lee, Feng Wang, Dennis Flynn, Robert B. Marks, Andre Gunder Frank and Jack Goody and John M. Hobson. The name of the approach is due to most of these scholars working at Californian universities. In comparing the Rest with the West, Vries critically reviewing their approach notes some differences in the emphasis of different scholars. Some argue that Europe was more backward, some that Asia was more advanced, some that Europe climbed on top of Asia via various forms of exploitation and some that the West and the Rest were really not that different. This later he refers to as the Eurasian similarity-thesis. Of importance in their analysis, according to Jack Goldstone, is the continuing high productivity of both agricultural and manufacturing technology in India and China with them remaining world-dominant powers up to the end of the 17th Century. This, and the relatively high living standards, and competitive nature of their merchants, who were at least the equal of European trading companies in terms of power until the end of the 17th century. Pomeranz, who is perhaps the dominant figure in the approach, emphasises the access to natural resources, rather than the alleged specialness of European capitalism, with its cultures of enlightenment and bourgeois virtues.