Poetry, also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

Rhyme royal is a rhyming stanza form that was introduced to English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer. The form enjoyed significant success in the fifteenth century and into the sixteenth century. It has had a more subdued but continuing influence on English verse in more recent centuries.

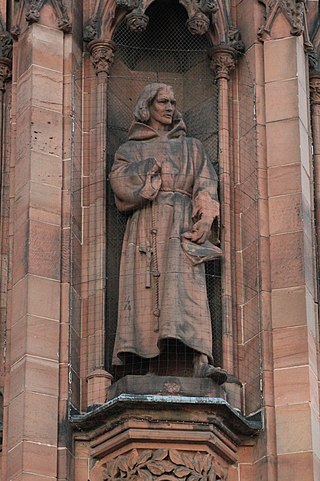

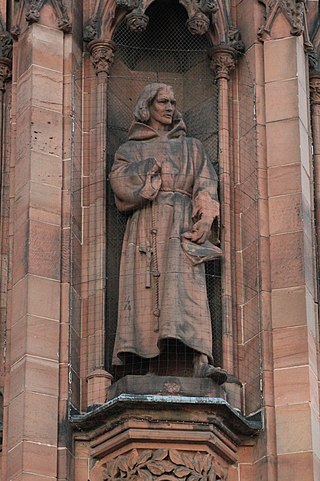

Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount was a Scottish knight, poet, and herald who gained the highest heraldic office of Lyon King of Arms. He remains a well regarded poet whose works reflect the spirit of the Renaissance, specifically as a makar.

William Dunbar was a Scottish makar, or court poet, active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. He was closely associated with the court of King James IV and produced a large body of work in Scots distinguished by its great variation in themes and literary styles. He was probably a native of East Lothian, as assumed from a satirical reference in The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie. His surname is also spelt Dumbar.

Robert Henryson was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots makars, he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in the Northern Renaissance at a time when the culture was on a cusp between medieval and renaissance sensibilities. Little is known of his life, but evidence suggests that he was a teacher who had training in law and the humanities, that he had a connection with Dunfermline Abbey and that he may also have been associated for a period with Glasgow University. His poetry was composed in Middle Scots at a time when this was the state language. His writing consists mainly of narrative works. His surviving body of work amounts to almost 5000 lines.

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

Flyting or fliting, is a contest consisting of the exchange of insults between two parties, often conducted in verse.

Hárbarðsljóð is one of the poems of the Poetic Edda, found in the Codex Regius and AM 748 I 4to manuscripts. It is a flyting poem with figures from Norse Paganism. Hárbarðsljóð was first written down in the late 11th century but may have had an older history as an oral poem.

Alexander Montgomerie was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which was still part of the Scottish Gàidhealtachd in his day. He was one of the principal members of the Castalian Band, a circle of poets in the court of James VI in the 1580s which included the king himself. Montgomerie was for a time in favour as one of the king's "favourites". He was a Catholic in a largely Protestant court and his involvement in political controversy led to his expulsion as an outlaw in the mid-1590s.

A makar is a term from Scottish literature for a poet or bard, often thought of as a royal court poet.

Richard Holland or Richard de Holande was a Scottish cleric and poet, author of the Buke of the Howlat.

"I that in Heill wes and Gladnes", also known as "The Lament for the Makaris", is a poem in the form of a danse macabre by the Scottish poet William Dunbar. Every fourth line repeats the Latin refrain timor mortis conturbat me, a litanic phrase from the Office of the Dead.

Galwegian Gaelic is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the early modern period. Little has survived of the dialect, so that its exact relationship with other Gaelic language is uncertain.

The Passioun of Crist, which begins Hail, Cristin knycht, haill, etern confortour... is a long poem in Middle Scots by the Scottish makar Walter Kennedy, who was associated with the renaissance court of James IV of Scotland. It is Kennedy's longest surviving work and a significant, though historically neglected work of Scottish literature.

The Castalian Band is a modern name given to a grouping of Scottish Jacobean poets, or makars, which is said to have flourished between the 1580s and early 1590s in the court of James VI and consciously modelled on the French example of the Pléiade. Its name is derived from the classical term Castalian Spring, a symbol for poetic inspiration. The name has often been claimed as that which the King used to refer to the group, as in lines from one of his own poems, an epitaph on his friend Alexander Montgomerie:

The Bannatyne Manuscript is an anthology of literature compiled in Scotland in the sixteenth century. It is an important source for the Scots poetry of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The manuscript contains texts of the poems of the great makars, many anonymous Scots pieces and works by medieval English poets.

Poetry of Scotland includes all forms of verse written in Brythonic, Latin, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French, English and Esperanto and any language in which poetry has been written within the boundaries of modern Scotland, or by Scottish people.

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (1375). Some ballads may date back to the thirteenth century, but were not recorded until the eighteenth century. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun's verse Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland and Blind Harry's The Wallace. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem The Kingis Quair. Writers such as William Dunbar, Robert Henryson, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. The first complete surviving work is John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s. The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid.

Walter Kennedy was a Scottish poet.

James Kinsley, FBA, FRSL was a Scottish literary scholar.