The Republic of Turkey was created after the overthrow of Sultan Mehmet VI Vahdettin by the new Republican Parliament in 1922. This new regime delivered the coup de grâce to the Ottoman state which had been practically wiped away from the world stage following the First World War.

The politics of Turkey take place in the framework of a presidential republic as defined by the Constitution of Turkey. The President of Turkey is both the head of state and head of government.

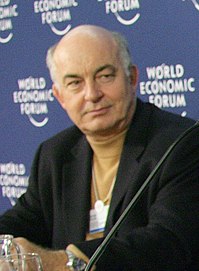

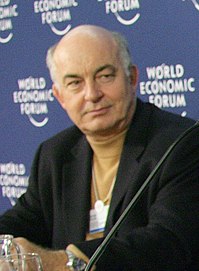

Kemal Derviş is a Turkish economist and politician, and former head of the United Nations Development Programme. He was honored by the government of Japan for having "contributed to mainstreaming Japan's development assistance policy through the United Nations". In 2005, he was ranked 67th in the Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll conducted by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. He is Vice President and Director of the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution and part-time professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a Turkish politician serving as the 12th and current president of Turkey since 2014. He previously served as prime minister of Turkey from 2003 to 2014 and as mayor of Istanbul from 1994 to 1998. He founded the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, leading it to election victories in 2002, 2007, and 2011 general elections before being required to stand down upon his election as President in 2014. He later returned to the AKP leadership in 2017 following the constitutional referendum that year. Coming from an Islamist political background and self-describing as a conservative democrat, he has promoted socially conservative and populist policies during his administration.

Kemalism, also known as Atatürkism, or The Six Arrows, is the founding official ideology of the Republic of Turkey. Kemalism, as it was implemented by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was defined by sweeping political, social, cultural and religious reforms designed to separate the new Turkish state from its Ottoman predecessor and embrace a Western-style modernized lifestyle; including the establishment of Secularism/Laicism (läicité), state support of the sciences, free education, & many more. Which most of those were first introduced to, and implemented in Turkey during Atatürk's presidency during and in his reforms.

The multi-party period of the Republic of Turkey started with the establishment of the opposition Liberal Republican Party by Ali Fethi Okyar in 1930 after President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk asked Okyar to establish the party as part of an attempted transition to multi-party democracy in Turkey. It was soon closed by the Republican People's Party government, however, when Atatürk found the party to be too influenced by Islamist-rooted reactionary elements.

The Dersim rebellion was an Alevi Kurdish uprising against the central government in the Dersim region of eastern Turkey, which includes parts of Tunceli Province, Elazığ Province, and Bingöl Province. The rebellion was led by Seyid Riza, a chieftain of the Abasan tribe. As a result of the Turkish Armed Forces campaign in 1937 and 1938 against the rebellion and the Dersim massacre, sometimes called the Dersim genocide, of civilians, thousands of Alevi Zazas died and many others were internally displaced.

Beşir Atalay is a Turkish politician who was Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey in the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from 2011 to 2014. Previously he was minister of interior from 28 August 2007 to 14 July 2011.

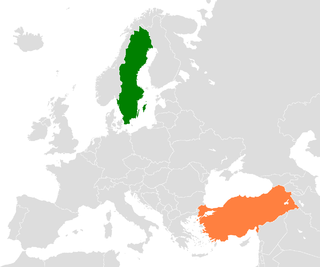

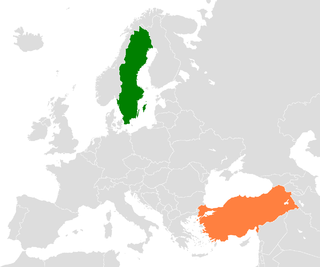

Swedish–Turkish relations are foreign relations between Sweden and Turkey. Both countries are full members of the Council of Europe, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the Union for the Mediterranean.

Democratic initiative process is the name of the process in which the government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan launched a project aiming to improve standards of democracy, freedoms and respect for human rights in Turkey. The project is called the Unity and Fraternity Project. Interior Minister Beşir Atalay stated the primary goals of the initiative as improving the democratic standards and to end terrorism in Turkey. "We will issue circulars in the short term, pass laws in the medium term, and make constitutional amendments in the long term and take required steps," Prime Minister Erdoğan said.

A constitutional referendum on a number of changes to the constitution was held in Turkey on 12 September 2010. The results showed the majority supported the constitutional amendments, with 58% in favour and 42% against. The changes were aimed at bringing the constitution into compliance with European Union standards. Supporters of Turkish EU membership hope constitutional reform will facilitate the membership process.

Turkey's 17th general election was held on 12 June 2011 to elect 550 new members of Grand National Assembly. In accordance to the result of the constitutional referendum held in 2007, the election was held four years after the previous one instead of five.

The foreign policy of the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan government concerns the policy initiatives made by Turkey towards other states under Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Presidential elections were held in Turkey on 10 August 2014 in order to elect the 12th President. Incumbent Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was elected outright with an absolute majority of the vote in the first round, making a scheduled run-off for 24 August unnecessary.

Atatürk's cult of personality was started during the life of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and continued by his successors after his death in 1938, by members of both his Republican People's Party and opposition parties alike, and in a limited amount by himself during his lifetime in order to popularize and cement his social and political reforms as a founder and the first President of Turkey. British journalist, Alexander Christie-Miller, has described it as the "world's longest-running personality cult".

The Justice and Development Party Vice President announced that their candidate for 2014 Turkish presidential election was going to be the Prime Minister and the party leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Erdoğan accepted the nomination and ran a 40-day campaign which ended in victory. Erdoğan was elected the 12th President of Turkey and was sworn in on August 28, 2014.

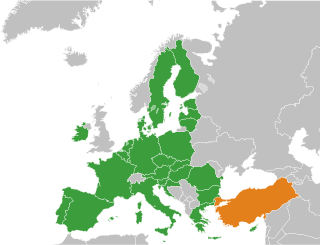

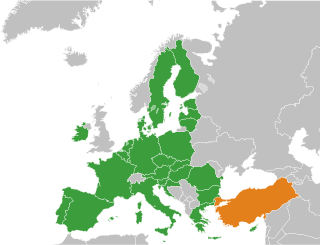

Relations between the European Union (EU) and Turkey were established in 1959, and the institutional framework was formalized with the 1963 Ankara Agreement. Albeit not officially part of the European Union, Turkey is one of the EU's main partners and both are members of the European Union–Turkey Customs Union. Turkey borders two EU member states: Bulgaria and Greece.

Erdoğanism or Tayyipism refers to the political ideals and agenda of Turkish President and former Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who became Prime Minister in 2003 and served until his election to the Presidency in 2014. With support significantly derived from charismatic authority, Erdoğanism has been described as the "strongest phenomenon in Turkey since Kemalism" and used to enjoy broad support throughout the country until the 2018 Turkish economic crisis which caused a significant decline in Erdoğan's popularity. Its ideological roots originate from Turkish conservatism and its most predominant political adherent is the governing Justice and Development Party, a party that Erdoğan himself founded in 2001.

The presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan began when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan took the oath of office on 28 August 2014 and became the 12th president of Turkey. He administered the new Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu's oath on 29 August. When asked about his lower-than-expected 51.79% share of the vote, he allegedly responded, "there were even those who did not like the Prophet. I, however, won 52%." Assuming the role of President, Erdoğan was criticized for openly stating that he would not maintain the tradition of presidential neutrality. Erdoğan has also stated his intention to pursue a more active role as President, such as utilising the President's rarely used cabinet-calling powers. The political opposition has argued that Erdoğan will continue to pursue his own political agenda, controlling the government, while his new Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu would be docile and submissive. Furthermore, the domination of loyal Erdoğan supporters in Davutoğlu's cabinet fuelled speculation that Erdoğan intended to exercise substantial control over the government.

The public image of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan concerns the image of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, current President of Turkey, among residents of Turkey and worldwide.