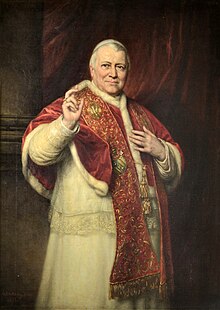

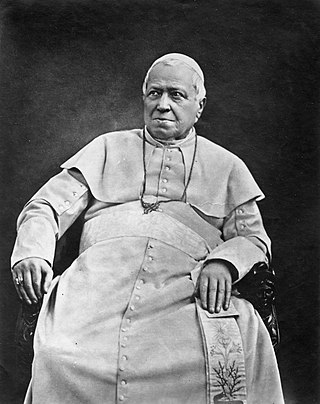

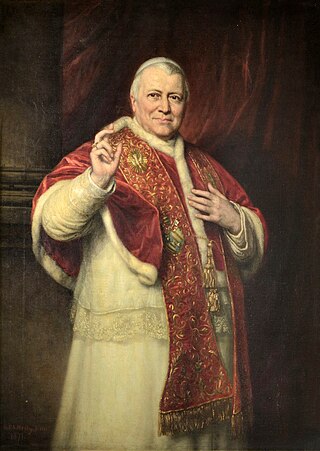

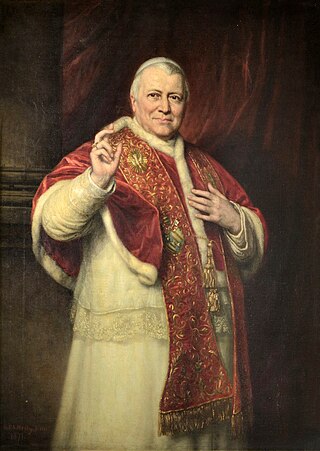

The theology of Pope Pius IX championed the pontiff's role as the highest teaching authority in the Church. [1]

The theology of Pope Pius IX championed the pontiff's role as the highest teaching authority in the Church. [1]

He promoted the foundations of Catholic Universities in Belgium and France and supported Catholic associations with the intellectual aim to explain the faith to non-believers and non-Catholics. The Ambrosian Circle in Italy, the Union of Catholic Workers in France and the Pius Verein and the Deutsche Katholische Gesellschaft in Germany all tried to bring the Catholic faith in its fullness to people outside of the Church. [2]

Pope Pius IX was deeply religious and shared a strong devotion to the Virgin Mary with many of his contemporaries, who made major contributions to Roman Catholic Mariology. Marian doctrines featured prominently in 19th century theology, especially the issue of the Immaculate Conception of Mary. During his pontificate petitions increased requesting the dogmatization of the Immaculate Conception. In 1848 Pius appointed a theological commission to analyze the possibility for a Marian dogma. [3]

In a record 38 encyclicals, Pius took positions on Church issues. They include: Qui pluribus (1846) on faith and religion; Praedecessores nostros (1847) on aid for Ireland; Ubi primum 1849 on the Immaculate Conception; Nostis et nobiscum 1849 on the Church in the Papal States; Neminem vestrum 1854 on the bloody persecution of Armenians; Cum nuper 1858 on care for clerics; Amantissimus 1862 on the care of the churches; Meridionali Americae 1865 on the Seminary for the Native Clergy; Omnem sollicitudinem 1874 on the Greek-Ruthenian Rite; Quod nunquam 1875 on the Church in Prussia. On 7 February 1862 he issued the papal constitution Ad universalis Ecclesiae dealing with the conditions for admission to religious orders in which solemn vows are prescribed. Unlike popes in the 20th century, Pius IX did not use encyclicals to explain the faith in its details, but to show problem areas and errors in the Church and in various countries. [4]

His December 1864 encyclical Quanta cura contained the Syllabus of Errors , an appendix that listed and condemned as heresy 80 propositions, many on political topics, and firmly established his pontificate in opposition to secularism, rationalism, and modernism in all its forms. The document affirmed that the Church is a true and perfect society entirely free, endowed with proper and perpetual rights of her own, conferred upon her by her Divine Founder, supreme over any secular authority. [5] [6] The ecclesiastical power can exercise its authority without the permission and assent of the civil government. [7] [8] The Church has the power of defining dogmatically that the religion of the Catholic Church is the only true religion. [5] [9] After centuries of being dominated by States and secular powers, the Pope thus defended the rights of the Church to free expression and opinion, even if particular views violated the perception and interests of secular forces, which in Italy at the time tried to dominate many Church activities, episcopal appointments, and even the education of the clergy in seminaries.

The Syllabus nevertheless was controversial at the time. "The Pope whose influence and State was seen as declining, even ending before the Syllabus, was at once the center of attention as the powerful enemy of progress, a man of boundless power and dangerous influence." [10] Anti-Catholic forces viewed the papal document as an attack on progress, while many Catholics were happy to see their rights defined and defended against the encroachment of national governments. [11] European Catholics welcomed the idea that national churches are not subject to state authority, [11] an idea long practiced in France, Spain, and Portugal under various versions of Gallicanism. American Catholics, who saw agreement of the papal views on the role of the State in Church affairs with those of the founding fathers, rejoiced over the definition of temporal rights in the areas of education, marriage and family. [11]

Pius IX was the first pope to popularize encyclicals on a large scale to foster his views. He decisively acted on the century-old struggle between Dominicans and Franciscans regarding the Immaculate Conception of Mary, deciding in favour of the latter ones. [12] However, this decision, which he formulated as an infallible dogma, raised the question, can a Pope in fact make such decisions without the bishops? This foreshadowed one topic of the Vatican Council which he later convened for 1869. [13] The Pope did consult the bishops beforehand with his encyclical Ubi Primum (see below), but insisted on having this issue clarified nevertheless. The Council was to deal with Papal Infallibility not on its own but as an integral part of its consideration of the definition of the Catholic Church and the role of the bishops in it. [13] As it turned out, this was not possible because of the imminent attack by Italy against the Papal States, which forced a premature suspension of the First Vatican Council. Thus the major achievements of Pius IX are his Mariology and Vatican I. [13]

The Vatican Council did prepare several decrees, which, with small changes, were all signed by Pius IX. They refer to the Catholic faith, God the creator of all things, divine revelation, the relation between faith and human reasoning, the primacy of the papacy and the infallibility of the papacy. It was noted that the theological style of Pius was often negative, stating obvious errors rather than stating what is right. [14] Pius was noted for overstating his case at times, which was explained in part due to his epileptic condition. This created problems inside and outside the Church but also resulted in a clearing of the air and in much attention to his utterings, which otherwise may not have materialized. [14]

Contrary to stiff ultra-conservative sterility, which some attempted to associate with Pius IX, an extraordinary renewal of Catholic vigour and religious life took place during his pontificate: The entire episcopate was reappointed, and religious orders and congregations experienced a growth and vitality, which was not anticipated by anyone at the beginning of his papacy in 1846. [15] Existing orders had numerous applications and expanded, sending many of their “excess” vocation to missionary activities in Africa and Asia. Pius IX approved 74 new ones for women alone. [15] In France, where the Church was devastated after the French Revolution, there were 160.000 Religious when Pius IX died in 1878, in addition to the regular priests, working in the parishes. Pius created over 200 news bishop seats, oversaw an unprecedented growth of the Church in the USA and created new hierarchies in several countries. [15]

Encouraged by Rome, Catholic lay people began to participate again in pilgrimages, spiritual retreats, baptisms and confessions and Catholic associations of all kinds. [16] The great number of vocations led Pius to issue several admonitions to Bishops, to weed out candidates with moral weaknesses. [17] He founded several seminaries in Rome, to ensure that only the best are admitted to the priestly service. Lazy priests or priests who did not perform were punished or dismissed from their service. [18] On the other hand, he also reformed the system of Church discipline, getting rid of some indulgences, causes for excommunication, suspensions of clergy and other disciplinary measures. He did not, however, undertake an overall reform of Canon Law. [16]

Catholic monasteries are officially not under the local jurisdiction of the papacy, yet Pius IX on 21 June 1847, addressed them and asked for reforms. He wrote, that monasteries form an indispensable bridge between the secular and religious world and fulfill therefore an important function for the Church as a whole. He mandated a reform of monastic discipline and outlawed century old practices, by which men and women were given eternal vows and forced to stay in the convent or monastery without prior probation periods. He mandated a waiting period of three years for entry into a monastery, and declared all monastic vows without the three years as invalid. [19] Specifics included reform of the monastic habits, music and the theological preparation in the monasteries. most but not all of them accepted the reforms of the Pope. [19] Pius did not hesitate to impose reform-minded superiors in several congregations. A special relation existed between him and the Jesuit order, which had educated him as a young boy. Jesuits were said to be influential during his pontificate, which created misgivings and animosity in the secular media at the time. [1]

Pope Leo XIII was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the oldest pope holding office, and the second-longest-lived pope in history after Pope Benedict XVI as Pope emeritus. He also had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of St. Peter, Pius IX and John Paul II.

Pope Pius IX was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican Council in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the Papal States in 1870 to the Kingdom of Italy. Thereafter, he refused to leave Vatican City, declaring himself a "prisoner of the Vatican".

Pope Pius X was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of Catholic doctrine, and for promoting liturgical reforms and scholastic theology. He initiated the preparation of the 1917 Code of Canon Law, the first comprehensive and systemic work of its kind. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church. The Society of Saint Pius X, a traditionalist Catholic fraternity, is named after him.

The magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church is the church's authority or office to give authentic interpretation of the Word of God, "whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition." According to the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, the task of interpretation is vested uniquely in the Pope and the bishops, though the concept has a complex history of development. Scripture and Tradition "make up a single sacred deposit of the Word of God, which is entrusted to the Church", and the magisterium is not independent of this, since "all that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed is derived from this single deposit of faith."

The history of the papacy, the office held by the pope as head of the Catholic Church, spans from the time of Peter, to the present day. Moreover, many of the bishops of Rome in the first three centuries of the Christian era are obscure figures. Most of Peter's successors in the first three centuries following his life suffered martyrdom along with members of their flock in periods of persecution.

Munificentissimus Deus is the name of an apostolic constitution written by Pope Pius XII. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was the first ex-cathedra infallible statement since the official ruling on papal infallibility was made at the First Vatican Council (1869–1870). In 1854 Pope Pius IX made an infallible statement with Ineffabilis Deus on the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, which was a basis for this dogma. The decree was promulgated on 1 November 1950.

Ineffabilis Deus is an apostolic constitution by Pope Pius IX. It defines the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The document was promulgated on December 8, 1854, the date of the annual Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, and followed from a positive response to the encyclical Ubi primum.

The history of Catholic Mariology traces theological developments and views regarding Mary from the early Church to the 21st century. Mariology is a mainly Catholic ecclesiological study within theology, which centers on the relation of Mary, the Mother of God, and the Church. Theologically, it not only deals with her life but with her veneration in life and prayer, in art, music, and architecture, from ancient Christianity to modern times.

The Mariology of the popes is the theological study of the influence that the popes have had on the development, formulation and transformation of the Roman Catholic Church's doctrines and devotions relating to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

A dogma of the Catholic Church is defined as "a truth revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church declared as binding". The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

The Church's Magisterium asserts that it exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging Catholics to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these.

Mariological papal documents have been a major force that has shaped Roman Catholic Mariology over the centuries. Mariology is developed by theologians on the basis not only of Scripture and Tradition but also of the sensus fidei of the faithful as a whole, "from the bishops to the last of the faithful", and papal documents have recorded those developments, defining Marian dogmas, spreading doctrines and encouraging devotions within the Catholic Church.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

Ubi primum is an encyclical of Pope Pius IX to the bishops of the Catholic Church asking them for opinion on the definition of a dogma on the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. It was issued on February 2, 1849.

Le pèlerinage de Lourdes is the only encyclical of Pope Pius XII issued in French. It includes warnings against materialism on the centenary of the apparitions at Lourdes. It was given at Rome, from St. Peter's Basilica, on the feast of the Visitation of the Most Holy Virgin, July 2, 1957, the nineteenth year of his pontificate.

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks ex cathedra is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apostolic Church and handed down in Scripture and tradition". It does not mean that the pope cannot sin or otherwise err in most situations.

The foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and France were characterized by the hostility of the Third Republic's anticlerical politics, as well as Napoleon III's influence over the papal states. This did not stop, however, Church life in France from flourishing during much of Pius IX's pontificate.

Foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and Italy were characterized by an extensive political and diplomatic conflict over Italian unification and the subsequent status of Rome after the victory of the liberal revolutionaries.

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

The theology of Pope Leo XIII was influenced by the ecclesial teachings of the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), which had ended only eight years before his election in 1878. Leo issued some 46 apostolic letters and encyclicals dealing with central issues in the areas of marriage and family and state and society.

The modern history of the papacy is shaped by the two largest dispossessions of papal property in its history, stemming from the French Revolution and its spread to Europe, including Italy.