Related Research Articles

Rollo Duke of Normandy, also known as The Bloody Brother, is a play written in collaboration by John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson and George Chapman. The title character is the historical Viking duke of Normandy, Rollo. Scholars have disputed almost everything about the play; but it was probably written sometime in the 1612–24 era and later revised, perhaps in 1630 or after. In addition to the four writers cited above, the names of Nathan Field and Robert Daborne have been connected with the play by individual scholars.

Francis Beaumont was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

Theuderic II (587–613), king of Burgundy (595–613) and Austrasia (612–613), was the second son of Childebert II. At his father's death in 595, he received Guntram's kingdom of Burgundy, with its capital at Orléans, while his elder brother, Theudebert II, received their father's kingdom of Austrasia, with its capital at Metz. He also received the lordship of the cities (civitates) of Toulouse, Agen, Nantes, Angers, Saintes, Angoulême, Périgueux, Blois, Chartres, and Le Mans. During his minority, and later, he reigned under the guidance of his grandmother Brunhilda, evicted from Austrasia by his brother Theudebert II.

John Fletcher was an English playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King's Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; during his lifetime and in the Stuart Restoration, his fame rivalled Shakespeare's. Fletcher collaborated in writing plays, chiefly with Francis Beaumont or Philip Massinger, but also with Shakespeare and others.

The Duke of Milan is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragedy written by Philip Massinger. First published in 1623, the play is generally considered among the author's finest achievements in drama.

Cupid's Revenge is a Jacobean tragedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. It was a popular success that influenced subsequent works by other authors.

Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding is an early Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. One of the duo's earliest successes, the play helped to establish the trend for tragicomedy that was a powerful influence in early Stuart-era drama.

The Maid of Honour is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Philip Massinger, first published in 1632. It may be Massinger's earliest extant solo work.

The Queen of Corinth is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators. It was initially published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

The Prophetess is a late Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger. It was initially published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

The Elder Brother is an early seventeenth-century English stage play, a comedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger. Apparently dating from 1625, it may have been the last play Fletcher worked on before his August 1625 death.

The Spanish Curate is a late Jacobean era stage play, a comedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger. It premiered on the stage in 1622, and was first published in 1647.

The Double Marriage is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragedy written by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, and initially printed in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

Beggars' Bush is a Jacobean era stage play, a comedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators that is a focus of dispute among scholars and critics.

Love's Cure, or The Martial Maid is an early seventeenth-century stage play, a comedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators. First published in the Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647, it is the subject of broad dispute and uncertainty among scholars. In the words of Gerald Eades Bentley, "nearly everything about the play is in a state of confusion...."

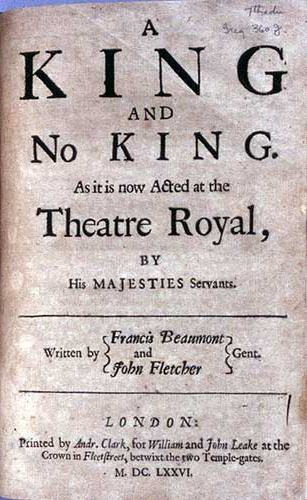

A King and No King is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher and first published in 1619. It has traditionally been among the most highly praised and popular works in the canon of Fletcher and his collaborators.

The Scornful Lady is a Jacobean era stage play, a comedy written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, and first published in 1616, the year of Beaumont's death. It was one of the pair's most popular, often revived, and frequently reprinted works.

The Noble Gentleman is a Jacobean era stage play, a comedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators that was first published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647. It is one of the plays in Fletcher's canon that presents significant uncertainties about its date and authorship.

Thomas Walkley was a London publisher and bookseller in the early and middle seventeenth century. He is noted for publishing a range of significant texts in English Renaissance drama, "and much other interesting literature."

References

- ↑ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, p. 230.

- ↑ E. H. C. Oliphant, The Plays of Beaumont and Fletcher: An Attempt to Determine Their Respective Shares and the Shares of Others, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1927; pp. 276–7.

- ↑ Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Later Jacobean and Caroline Dramatists: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1978; p. 69.

- ↑ Oliphant, pp. 277–8.

- ↑ Edmund Gosse, The Jacobean Poets, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1894; p. 81.