Related Research Articles

Diocletian was a Roman emperor from 284 to 305. Born to a family of low status in Dalmatia, Diocletian rose as an Illyriciani through the ranks of the military to become a cavalry commander of the Emperor Carus's army. After the deaths of Carus and his son Numerian on campaign in Persia, Diocletian was proclaimed emperor. The title was also claimed by Carus's surviving son, Carinus, but Diocletian defeated him in the Battle of the Margus.

The 290s decade ran from January 1, 290, to December 31, 299.

The 280's decade ran from January 1, 280, to December 31, 289.

Flavius Valerius Constantius "Chlorus", also called Constantius I, was a Roman emperor as one of the four original members of the "Tetrarchy" established by Diocletian in 293. He was a junior-ranking emperor, or Caesar, from 293 to 305, and senior emperor, Augustus, from 305 to 306. Constantius was also father of Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor of Rome. The nickname Chlorus was first popularized by Byzantine-era historians and not used during the emperor's lifetime.

Numerian was Roman emperor from 283 to 284 with his older brother Carinus. They were sons of Carus, a general raised to the office of praetorian prefect under Emperor Probus in 282.

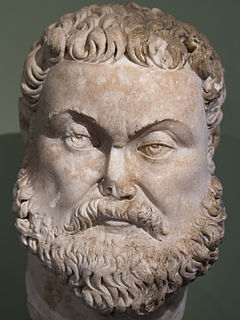

Maximian, nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was Caesar from 285 to 286, then Augustus from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocletian, whose political brain complemented Maximian's military brawn. Maximian established his residence at Trier but spent most of his time on campaign. In late 285, he suppressed rebels in Gaul known as the Bagaudae. From 285 to 288, he fought against Germanic tribes along the Rhine frontier. Together with Diocletian, he launched a scorched earth campaign deep into Alamannic territory in 288, temporarily relieving the Rhine provinces from the threat of Germanic invasion.

Marcus Aurelius Carinus was Roman emperor from 283 to 285. The elder son of emperor Carus, he was first appointed Caesar and in the beginning of 283 co-emperor of the western portion of the empire by his father. Official accounts of his character and career, which portray him as debauched and incapable, have been filtered through the propaganda of his successful opponent, Diocletian.

Philip Massinger was an English dramatist. His finely plotted plays, including A New Way to Pay Old Debts, The City Madam, and The Roman Actor, are noted for their satire and realism, and their political and social themes.

Rollo Duke of Normandy, also known as The Bloody Brother, is a play written in collaboration by John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson and George Chapman. The title character is the historical Viking duke of Normandy, Rollo. Scholars have disputed almost everything about the play; but it was probably written sometime in the 1612–24 era and later revised, perhaps in 1630 or after. In addition to the four writers cited above, the names of Nathan Field and Robert Daborne have been connected with the play by individual scholars.

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

John Fletcher (1579–1625) was a Jacobean playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King's Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; during his lifetime and in the early Restoration, his fame rivalled Shakespeare's. He collaborated on writing plays with Francis Beaumont, and also with Shakespeare on two plays.

Dioclesian is a tragicomic semi-opera in five acts by Henry Purcell to a libretto by Thomas Betterton based on the play The Prophetess, by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, which in turn was based very loosely on the life of the Emperor Diocletian. It was premiered in late May 1690 at the Queen's Theatre, Dorset Garden. The play was first produced in 1622. Choreography for the various dances was provided by Josias Priest, who worked with Purcell on several other semi-operas.

Marcus Aurelius Sabinus Julianus was a Roman usurper against Emperor Carinus or Maximian. It is possible that up to four usurpers with a similar name rebelled in a timeframe of a decade, but at least one of them is known by numismatic evidence.

The Emperor of the East is a Caroline era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Philip Massinger and first published in 1632. The play provides an interesting example of the treatment of the Roman Catholic sacrament of confession in English Renaissance theatre.

The Maid of Honour is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Philip Massinger, first published in 1632. It may be Massinger's earliest extant solo work.

The Virgin Martyr is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragedy written by Thomas Dekker and Philip Massinger, and first published in 1622. It constitutes a rare instance in Massinger's canon in which he collaborated with a member of the previous generation of English Renaissance dramatists — those who began their careers in the 1590s, the generation of Shakespeare, Lyly, Marlowe and Peele.

The False One is a late Jacobean stage play by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, though formerly placed in the Beaumont and Fletcher canon. It was first published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

Beggars' Bush is a Jacobean era stage play, a comedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators that is a focus of dispute among scholars and critics.

Love's Cure, or The Martial Maid is an early seventeenth-century stage play, a comedy in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators. First published in the Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647, it is the subject of broad dispute and uncertainty among scholars. In the words of Gerald Eades Bentley, "nearly everything about the play is in a state of confusion...."

Aper was a Roman citizen of the third century AD. First known to history as a high-flying professional soldier, he went on to serve as an acting provincial governor and finally became Praetorian prefect, under the Emperor Carus - in effect vice principis. This rendered him hugely influential in the government of the empire - not excepting in matters of Peace and War.

References

- ↑ Terence P. Logan and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The Later Jacobean and Caroline Dramatists: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1978; pp. 76, 108.

- ↑ E. H. C. Oliphant, The Plays of Beaumont and Fletcher: An Attempt to Determine Their Respective Shares and the Shares of Others, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1927; p. 245.

- ↑ Logan and Smith, p. 76.

- ↑ Arthur Colby Sprague, Beaumont and Fletcher on the Restoration Stage, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1926; pp. 154–60.

- ↑ Gordon McMullan, The Politics of Unease in the Plays of John Fletcher. Amherst, MA, University of Massachusetts Press, 1994; pp. 183 and ff.