Thomas Sumter was an American military officer, planter, and politician who served in the Continental Army as a brigadier-general during the Revolutionary War. After the war, Sumter was elected to the House of Representatives and to the Senate, where he served from 1801 to 1810, when he retired. Sumter was nicknamed the "Fighting Gamecock" for his military tactics during the Revolutionary War.

Tuskegee was an Overhill Cherokee town located along the lower Little Tennessee River in what is now Monroe County, Tennessee, United States. The town developed in the late 1750s alongside Fort Loudoun, and was inhabited until the late 1770s. It was forcibly evacuated and probably burned during the Cherokee–American wars.

Chota is a historic Overhill Cherokee town site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Developing after nearby Tanasi, Chota was the most important of the Overhill towns from the late 1740s until 1788. It replaced Tanasi as the de facto capital, or 'mother town' of the Cherokee people.

Tanasi was a historic Overhill settlement site in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The village became the namesake for the state of Tennessee. It was abandoned by the Cherokee in the 19th century for a rising town whose chief was more powerful. Tanasi served as the de facto capital of the Overhill Cherokee from as early as 1721 until 1730, when the capital shifted to Great Tellico.

The Cherokee Path was the primary route of English and Scots traders from Charleston to Columbia, South Carolina in Colonial America. It was the way they reached Cherokee towns and territories along the upper Keowee River and its tributaries. In its lower section it was known as the Savannah River. They referred to these towns along the Keowee and Tugaloo rivers as the Lower Towns, in contrast to the Middle Towns in Western North Carolina and the Overhill Towns in present-day southeastern Tennessee west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Fort Loudoun was a British fort located in what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. Constructed from 1756 until 1757 to help garner Cherokee support for the British at the outset of the French and Indian War, the fort was one of the first significant British outposts west of the Appalachian Mountains. The fort was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm, while its construction was supervised by Captain Raymond Demeré; the fort's garrison was commanded by Demeré's brother, Paul Demeré. It was named for the Earl of Loudoun, the commander of British forces in North America at the time.

The Anglo-Cherokee War, was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherokee Rebellion. The war was a conflict between British forces in North America and Cherokee bands during the French and Indian War.

Conocotocko of Chota, known in English as Old Hop, was a Cherokee elder, serving as the First Beloved Man of the Cherokee from 1753 until his death in 1760. Settlers of European ancestry referred to him as Old Hop.

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American settlers on the frontier. Most of the events took place in the Upper South region. While the fighting stretched across the entire period, there were extended periods with little or no action.

Ostenaco was a Cherokee leader, warrior, orator, and leader of diplomacy with British colonial authorities in the 18th century. By his thirties, he had assumed the warrior rank of "otacity" (mankiller), and the title "tassite" of Great Tellico. He eventually rose to assume the higher Cherokee rank of chief-warrior.

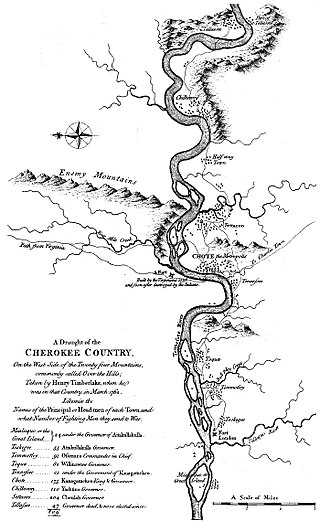

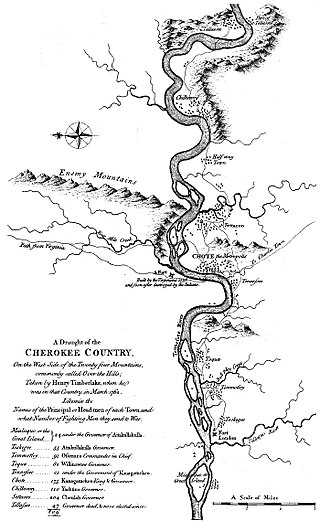

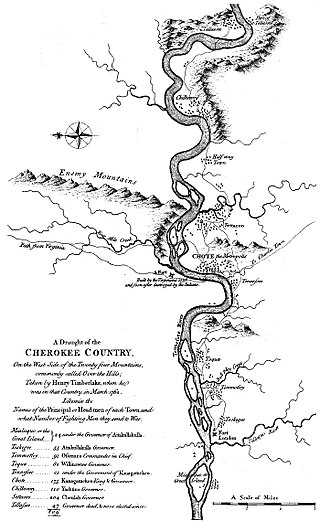

Overhill Cherokee was the term for the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used by 18th-century European traders and explorers from British colonies along the Atlantic coast, as they had to cross the mountains to reach these settlements.

Henry Timberlake was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the British colonies to the Overhill Cherokee during the 1761–1762 Timberlake Expedition.

Adam Stephen was a Scottish-born American doctor and military officer who helped found what became Martinsburg, West Virginia. He emigrated to North America, where he served in the Province of Virginia's militia under George Washington during the French and Indian War. He served under Washington again in the American Revolutionary War, rising to lead a division of the Continental Army. After a friendly fire incident during the Battle of Germantown, Stephen was cashiered out of the army but continued as a prominent citizen of western Virginia, including terms in the Virginia General Assembly representing Berkeley County.

Tomotley is a prehistoric and historic Native American site along the lower Little Tennessee River in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Occupied as early as the Archaic period, the Tomotley site was occupied particularly during the Mississippian period, which was likely when its earthwork platform mounds were built. It was also occupied during the eighteenth century as a Cherokee town. It revealed an unexpected style: an octagonal townhouse and square or rectangular residences. In the Overhill period, Cherokee townhouses found in the Carolinas in the same period were circular in design, with,

Citico is a prehistoric and historic Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The site's namesake Cherokee village was the largest of the Overhill towns, housing an estimated Indian population of 1,000 by the mid-18th century. The Mississippian village that preceded the site's Cherokee occupation is believed to have been the village of "Satapo" visited by the Juan Pardo expedition in 1567.

Chilhowee was a prehistoric and historic Native American site in present-day Blount and Monroe counties in Tennessee, in what were the Southeastern Woodlands. Although now submerged by the Chilhowee Lake impoundment of the Little Tennessee River, the Chilhowee site was home to a substantial 18th-century Overhill Cherokee town. It may have been the site of the older Creek village "Chalahume" visited by Spanish explorer Juan Pardo in 1567. The Cherokee later pushed the Muscogee Creek out of this area.

Tallassee is a prehistoric and historic Native American site in present-day Blount and Monroe counties, Tennessee in the southeastern United States. Tallassee was the southernmost of a string of Overhill Cherokee towns that existed along the lower Little Tennessee River on the west side of the Appalachian Mountains in the 18th century. Although Tallassee receives scant attention in primary historical accounts, it is one of the few Overhill towns to be shown on every major 18th-century map of the Little Tennessee Valley.

Bussell Island, formerly Lenoir Island, is an island located at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River, at its confluence with the Tennessee River in Loudon County, near the U.S. city of Lenoir City, Tennessee. The island was inhabited by various Native American cultures for thousands of years before the arrival of early European explorers. The Tellico Dam and a recreational area occupy part of the island. Part of the island was added in 1978 to the National Register of Historic Places for its archaeological potential.

The siege of Fort Loudoun was an engagement during the Anglo-Cherokee War fought from February 1760 to August 1760 between the warriors of the Cherokee led by Ostenaco and the garrison of Fort Loudoun composed of British and colonial soldiers commanded by Captain Paul Demeré.

A skiagusta, is a Cherokee title for a war chief, known as the 'red chief' in times of turmoil. The skiagusta was the highest possible rank for a red chief; however, he remained subordinate to the council of the 'white', or peace, chief in non-tactical matters, even during wartime.