A battleship is a large, heavily armored warship with a main battery consisting of large-caliber guns, designed to serve as capital ships with the most intense firepower. Before the rise of supercarriers, battleships were among the largest and most formidable weapon systems ever built.

The Imperial German Navy or the Kaiserliche Marine was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy, which was mainly for coast defence. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded the navy. The key leader was Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who greatly expanded the size and quality of the navy, while adopting the sea power theories of American strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. The result was a naval arms race with Britain, as the German navy grew to become one of the greatest maritime forces in the world, second only to the Royal Navy.

Erich Johann Albert Raeder was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939. Raeder led the Kriegsmarine for the first half of the war; he resigned in January 1943 and was replaced by Karl Dönitz. At the Nuremberg trials he was sentenced to life imprisonment but was released early owing to failing health in 1955.

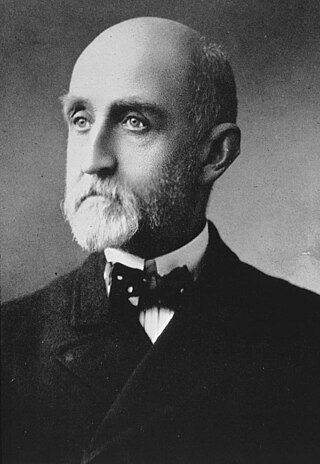

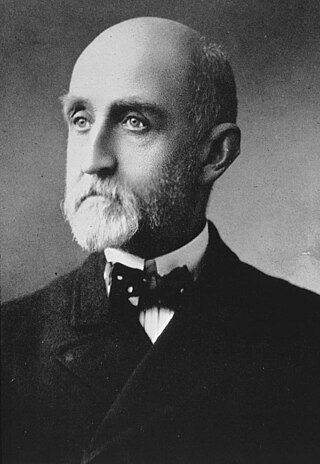

Alfred Thayer Mahan was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His 1890 book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 won immediate recognition, especially in Europe, and with the publication of its 1892 successor, The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812, he affirmed his status as a globally-known and regarded military strategist, historian, and theorist. Mahan's works encouraged the development of large capital ships — eventually leading to dreadnought battleships — as he was an advocate of the 'decisive battle' and of naval blockades. Critics, however, charged him with failing to adequately explain the rise of largely land-based empires, such as the German or Ottoman Empires, though Mahan did accurately predict both empires' defeats in World War I. Mahan directly influenced the dominant interwar period and World War II-era Japanese naval doctrine of the "decisive battle doctrine", and he became a "household name" in Germany. He also promoted American control over Hawaii though he was "lukewarm" in regards to American imperialism in general. Four U.S. Navy ships have borne his name, as well as various buildings and roads; and his works are still read, discussed, and debated in military, historical, and scholarly circles.

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916.

In naval warfare, a "fleet in being" is a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the enemy's actions, but while it remains safely in port, the enemy is forced to continually deploy forces to guard against it. A "fleet in being" can be part of a sea denial doctrine, but not one of sea control.

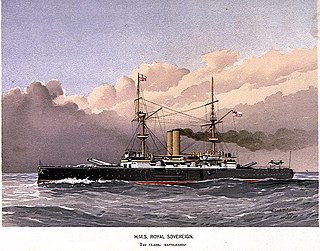

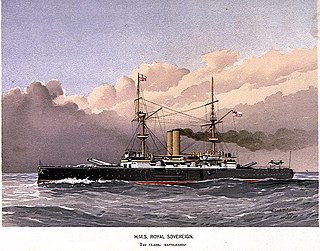

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of HMS Dreadnought in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively applied. In their day, they were simply known as "battleships" or else more rank-specific terms such as "first-class battleship" and so forth. The pre-dreadnought battleships were the pre-eminent warships of their time and replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s.

SMS Szent István was the last of four Tegetthoff-class dreadnought battleships built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Szent István was the only ship of her class to be built within the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a concession made to the Hungarian government in return for its support for the 1910 and 1911 naval budgets which funded the Tegetthoff class. She was built at the Ganz-Danubius shipyard in Fiume, where she was laid down in January 1912. She was launched two years later in 1914, but Szent István's construction was delayed due to the smaller shipyards in Fiume, and further delayed by the outbreak of World War I in July 1914. She was finally commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy in December 1915.

Although the history of the French Navy goes back to the Middle Ages, its history can be said to effectively begin with Richelieu under Louis XIII.

Naval warfare in World War I was mainly characterised by blockade. The Allied powers, with their larger fleets and surrounding position, largely succeeded in their blockade of Germany and the other Central Powers, whilst the efforts of the Central Powers to break that blockade, or to establish an effective counter blockade with submarines and commerce raiders, were eventually unsuccessful. Major fleet actions were extremely rare and proved less decisive.

The Naval Laws were five separate laws passed by the German Empire, in 1898, 1900, 1906, 1908, and 1912. These acts, championed by Kaiser Wilhelm II and his Secretary of State for the Navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, committed Germany to building up a navy capable of competing with the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom.

SMS Zähringen was the third Wittelsbach-class pre-dreadnought battleship of the German Imperial Navy. Laid down in 1899 at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel, she was launched on 12 June 1901 and commissioned on 25 October 1902. Her sisters were Wittelsbach, Wettin, Schwaben and Mecklenburg; they were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898, brought about by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. The ship, named for the former royal House of Zähringen, was armed with a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots.

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's HMS Dreadnought, had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts. Her design had two revolutionary features: an "all-big-gun" armament scheme, with an unprecedented number of heavy-calibre guns, and steam turbine propulsion. As dreadnoughts became a crucial symbol of national power, the arrival of these new warships renewed the naval arms race between the United Kingdom and Germany. Dreadnought races sprang up around the world, including in South America, lasting up to the beginning of World War I. Successive designs increased rapidly in size and made use of improvements in armament, armour, and propulsion throughout the dreadnought era. Within five years, new battleships outclassed Dreadnought herself. These more powerful vessels were known as "super-dreadnoughts". Most of the original dreadnoughts were scrapped after the end of World War I under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, but many of the newer super-dreadnoughts continued serving throughout World War II.

SMS Wettin was a pre-dreadnought battleship of the Wittelsbach class of the German Kaiserliche Marine. She was built by Schichau Seebeckwerft in Danzig. Wettin was laid down in October 1899, and was completed October 1902. She and her sister ships—Wittelsbach, Zähringen, Schwaben and Mecklenburg—were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898. Wettin was armed with a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots.

The Navy League or Fleet Association in Imperial Germany was an interest group formed on April 30, 1898 on initiative of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz through the German Imperial Naval Office (Reichsmarineamt) which he headed (1897–1916) to support the expansion of the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine). Specifically it was intended to develop popular pressure on the German parliament (Reichstag) to approve the Fleet Acts of 1898 and 1900, and the attendant expenses.

World War II saw the end of the battleship as the dominant force in the world's navies. At the outbreak of the war, large fleets of battleships—many inherited from the dreadnought era decades before—were one of the decisive forces in naval thinking. By the end of the war, battleship construction was all but halted, and almost every remaining battleship was retired or scrapped within a few years of its end.

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship that had worsened over many decades, the arms race began with a plan by German Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz in 1897 to create a fleet in being to force Britain to make diplomatic concessions; Tirpitz did not expect the Imperial German Navy to defeat the Royal Navy.

The High Seas Fleet was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet was renamed as the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; he envisioned a force powerful enough to challenge the Royal Navy's predominance. Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German Emperor, championed the fleet as the instrument by which he would seize overseas possessions and make Germany a global power. By concentrating a powerful battle fleet in the North Sea while the Royal Navy was required to disperse its forces around the British Empire, Tirpitz believed Germany could achieve a balance of force that could seriously damage British naval hegemony. This was the heart of Tirpitz's "Risk Theory", which held that Britain would not challenge Germany if the latter's fleet posed such a significant threat to its own.

Erich Johann Albert Raeder was a naval leader in Germany before and during World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank – that of Großadmiral – in 1939, becoming the first person to hold that rank since Alfred von Tirpitz. Raeder led the Kriegsmarine for the first half of the war; he resigned in 1943 and was replaced by Karl Dönitz. He was sentenced to life in prison at the Nuremberg Trials, but was released early due to failing health. Raeder is also well known for dismissing Reinhard Heydrich from the Reichsmarine in April 1931 for "conduct unbecoming to an officer and a gentleman".