The rufous trident bat, Persian trident bat, or triple nose-leaf bat is a species of bat in the genus Triaenops. It occurs in southwestern Pakistan, southern Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen. In the last country, it occurs together with the much smaller Triaenops parvus. Populations from Madagascar and mainland Africa have also been assigned to T. persicus, but are referable to the species Triaenops menamena and Triaenops afer, respectively. Madagascar populations have also been referred to as Triaenops rufus, but this name is a synonym of T. persicus.

Grandidier's trident bat is a species of bat in the family Hipposideridae endemic to Madagascar. It was formerly assigned to the genus Triaenops, but is now placed in the separate genus Paratriaenops.

Triaenops is a genus of bat in the family Hipposideridae. It is classified in the tribe Triaenopini, along with the closely related genus Paratriaenops and perhaps the poorly known Cloeotis. The species of Paratriaenops, which occur on Madagascar and the Seychelles, were placed in Triaenops until 2009. Triaenops currently contains the following species:

Paratriaenops furculus, also known as Trouessart's trident bat, is a species of bat in the family Hipposideridae. It is endemic to Madagascar. It was formerly assigned to the genus Triaenops, but is now placed in the separate genus Paratriaenops. A related species, Paratriaenops pauliani, occurs in the Seychelles.

Ambondro mahabo is a mammal from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) Isalo III Formation of Madagascar. The only described species of the genus Ambondro, it is known from a fragmentary lower jaw with three teeth, interpreted as the last premolar and the first two molars. The premolar consists of a central cusp with one or two smaller cusps and a cingulum (shelf) on the inner, or lingual, side of the tooth. The molars also have such a lingual cingulum. They consist of two groups of cusps: a trigonid of three cusps at the front and a talonid with a main cusp, a smaller cusp, and a crest at the back. Features of the talonid suggest that Ambondro had tribosphenic molars, the basic arrangement of molar features also present in marsupial and placental mammals. It is the oldest known mammal with putatively tribosphenic teeth; at the time of its discovery it antedated the second oldest example by about 25 million years.

UA 8699 is a fossil mammalian tooth from the Cretaceous of Madagascar. A broken lower molar about 3.5 mm (0.14 in) long, it is from the Maastrichtian of the Maevarano Formation in northwestern Madagascar. Details of its crown morphology indicate that it is a boreosphenidan, a member of the group that includes living marsupials and placental mammals. David W. Krause, who first described the tooth in 2001, interpreted it as a marsupial on the basis of five shared characters, but in 2003 Averianov and others noted that all those are shared by zhelestid placentals and favored a close relationship between UA 8699 and the Spanish zhelestid Lainodon. Krause used the tooth as evidence that marsupials were present on the southern continents (Gondwana) as early as the late Cretaceous and Averianov and colleagues proposed that the tooth represented another example of faunal exchange between Africa and Europe at the time.

Brachytarsomys mahajambaensis is an extinct rodent from northwestern Madagascar. It is known from nine isolated molars found in several sites during fieldwork that started in 2001. First described in 2010, it is placed in the genus Brachytarsomys together with two larger living species, which may differ in some details of molar morphology. The presence of B. mahajambaensis, a rare element in the local rodent fauna, suggests that the region was previously more humid.

Nesomys narindaensis is an extinct rodent that lived in northwestern Madagascar. It is known from subfossil skull bones and isolated molars found in several sites during field work that started in 2001. First described in 2010, it is placed in the genus Nesomys together with three smaller living species, which may differ in some details of molar morphology. The presence of N. narindaensis, a rare element in the local rodent fauna, suggests that the region was previously more humid.

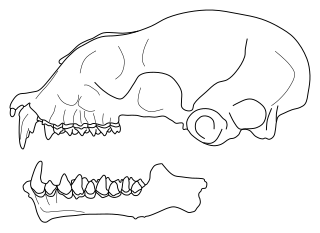

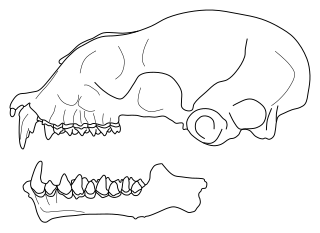

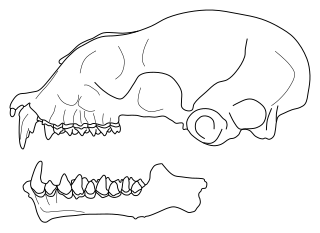

Hipposideros besaoka is an extinct bat from Madagascar in the genus Hipposideros. It is known from numerous jaws and teeth, which were collected in a cave at Anjohibe in 1996 and described as a new species in 2007. The site where H. besaoka was found is at most 10,000 years old; other parts of the cave have yielded H. commersoni, a living species of Hipposideros from Madagascar, and some material that is distinct from both species. H. besaoka was larger than H. commersoni, making it the largest insectivorous bat of Madagascar, and had broader molars and a more robust lower jaw. As usual in Hipposideros, the second upper premolar is small and displaced from the toothrow, and the second lower premolar is large.

Triaenops menamena is a bat in the genus Triaenops found on Madagascar, mainly in the drier regions. It was known as Triaenops rufus until 2009, when it was discovered that that name had been incorrectly applied to the species. Triaenops rufus is a synonym of Triaenops persicus, a Middle Eastern species closely related to T. menamena— the Malagasy species had previously been placed as a subspecies of T. persicus by some authors. Triaenops menamena is mostly found in forests, but also occurs in other habitats. It often roosts in large colonies and eats insects such as butterflies and moths. Because of its wide range, common occurrence, and tolerance of habitat degradation, it is not considered to be threatened.

Wabulacinus ridei lived during the early Miocene in Riversleigh. It is named after David Ride, who made the first revision of thylacinid fossils. The material was found in system C of the Camel Spurtum assembledge.

Dermotherium is a genus of fossil mammals closely related to the living colugos, a small group of gliding mammals from Southeast Asia. Two species are recognized: D. major from the Late Eocene of Thailand, based on a single fragment of the lower jaw, and D. chimaera from the Late Oligocene of Thailand, known from three fragments of the lower jaw and two isolated upper molars. In addition, a single isolated upper molar from the Early Oligocene of Pakistan has been tentatively assigned to D. chimaera. All sites where fossils of Dermotherium have been found were probably forested environments and the fossil species were probably forest dwellers like living colugos, but whether they had the gliding adaptations of the living species is unknown.

Afrasia djijidae is a fossil primate that lived in Myanmar approximately 37 million years ago, during the late middle Eocene. The only species in the genus Afrasia, it was a small primate, estimated to weigh around 100 grams (3.5 oz). Despite the significant geographic distance between them, Afrasia is thought to be closely related to Afrotarsius, an enigmatic fossil found in Libya and Egypt that dates to 38–39 million years ago. If this relationship is correct, it suggests that early simians dispersed from Asia to Africa during the middle Eocene and would add further support to the hypothesis that the first simians evolved in Asia, not Africa. Neither Afrasia nor Afrotarsius, which together form the family Afrotarsiidae, is considered ancestral to living simians, but they are part of a side branch or stem group known as eosimiiforms. Because they did not give rise to the stem simians that are known from the same deposits in Africa, early Asian simians are thought to have dispersed from Asia to Africa more than once prior to the late middle Eocene. Such dispersals from Asia to Africa also were seen around the same time in other mammalian groups, including hystricognathous rodents and anthracotheres.

Indraloris is a fossil primate from the Miocene of India and Pakistan in the family Sivaladapidae. Two species are now recognized: I. himalayensis from Haritalyangar, India and I. kamlialensis from the Pothohar Plateau, Pakistan. Other material from the Potwar Plateau may represent an additional, unnamed species. Body mass estimates range from about 2 kg (4.4 lb) for the smaller I. kamlialensis to over 4 kg (8.8 lb) for the larger I. himalayensis.

Paratriaenops is a genus in the bat family Hipposideridae. It is classified in the tribe Triaenopini, along with the closely related genus Triaenops and perhaps the poorly known Cloeotis. The species of Paratriaenops were placed in Triaenops until 2009. Paratriaenops currently contains the following species:

Paratriaenops pauliani is a species of bat in the family Hipposideridae. It is endemic to Aldabra Atoll of the western Seychelles, where it was found on Picard Island. It was formerly considered to be part of the species Triaenops furculus, known from Madagascar, and was initially assigned as a new species within the genus Triaenops. Later it as well as T. furculus were placed in the separate genus Paratriaenops. A related species, Paratriaenops auritus, also of Madagascar, was similarly reassigned.

Submyotodon is a genus of vespertilionid bats, published as a new taxon in 2003 to describe a Miocene fossil species. Extant species and subspecies previously included in Myotis were later transferred to this genus. Species in this genus are referred to as broad-muzzled bats or broad-muzzled myotises.

Rhinonycteridae is a family of bats, allied to the suborder Microchiroptera. The type species, the orange nose-leafed species group Rhinonicteris aurantia, is found across the north of Australia.

Notoetayoa is an extinct genus of mammal, from the order Xenungulata. It lived during the Middle Paleocene, and its fossilized remains were discovered in South America.