Related Research Articles

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, but is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States. He is the first European documented as having crossed the Mississippi River.

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River, at the head of Apalachee Bay, an area known as the Apalachee Province. They spoke a Muskogean language called Apalachee, which is now extinct.

Tocobaga was the name of a chiefdom of Native Americans, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-day city of Tampa and northern Pinellas County. The exact location of the principal town is believed to be the archeological Safety Harbor site. This is the namesake for the Safety Harbor culture, of which the Tocobaga are the most well-known group.

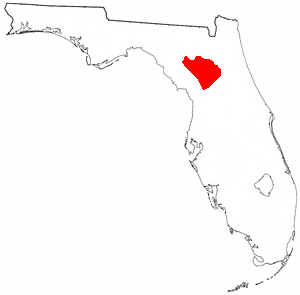

The Potano tribe lived in north-central Florida at the time of first European contact. Their territory included what is now Alachua County, the northern half of Marion County and the western part of Putnam County. This territory corresponds to that of the Alachua culture, which lasted from about 700 until 1700. The Potano were among the many tribes of the Timucua people, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language.

Utinahica was a town that was the site of a Spanish mission, Santa Isabel de Utinahica. It may have been the chief town of a Timucua tribe and chiefdom in the 17th century, but Hann says there is not enough known about it to be sure. The name means "lord's village". Utinahica, was called a "province" in one Spanish report. It was 30 leagues east of Arapaha, and 50 leagues northeast of the town of Tarihica in the Northern Utina Province. It was at or near where the Oconee and Ocmulgee rivers join to form the Altamaha River. The people of Utinahica apparently practiced a regional variant of the Lamar regional culture, unusual for a Timucuan-speaking people. Worth identifies the province of Utinahica with archaeological sites, including the Lind Landing site, Coffee Bluff site, and Bloodroot site, that have yielded artifacts of the Square Ground Lamar culture from before the 15th century until the middle of the 17th century. The Square Ground Lamar culture is otherwise associated with sites occupied by speakers of Muskogean languages. Archaeological sites identified with all other known Timucuan-speakers, with the possible exception of Guadalquini, do not have affinities with the Square Ground Lamar culture.

Mayaca was the name used by the Spanish to refer to a Native American tribe in central Florida, to the principal village of that tribe and to the chief of that village in the 1560s. The Mayacas occupied an area in the upper St. Johns River valley just to the south of Lake George. According to Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, the Mayaca language was related to that of the Ais, a tribe living along the Atlantic coast of Florida to the southeast of the Mayacas. The Mayacas were hunter-fisher-gatherers, and were not known to practice agriculture to any significant extent, unlike their neighbors to the north, the Utina, or Agua Dulce (Freshwater) Timucua. The Mayaca shared a ceramics tradition with the Freshwater Timucua, rather than the Ais.

Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact. The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

Tsala Apopka Lake is a chain of lakes located within a bend in the Withlacoochee River in Citrus County in north central Florida. This area is known historically as the Cove of the Withlacoochee.

The Indigenous peoples of Florida lived in what is now known as Florida for more than 12,000 years before the time of first contact with Europeans. However, the indigenous Floridians living east of the Apalachicola River had largely died out by the early 18th century. Some Apalachees migrated to Louisiana, where their descendants now live; some were taken to Cuba and Mexico by the Spanish in the 18th century, and a few may have been absorbed into the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes.

Uzita (Uçita) was the name of a 16th-century native chiefdom, its chief town and its chiefs. Part of the Safety Harbor culture, it was located in present-day Florida on the south side of Tampa Bay.

Mocoso was the name of a 16th-century chiefdom located on the east side of Tampa Bay, Florida near the mouth of the Alafia River, of its chief town and of its chief. Mocoso was also the name of a 17th-century village in the province of Acuera, a branch of the Timucua. The people of both villages are believed to have been speakers of the Timucua language.

The Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) were a Timucua people of northeastern Florida. They lived in the St. Johns River watershed north of Lake George, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language also known as Agua Dulce.

The Northern Utina, also known as the Timucua or simply Utina, were a Timucua people of northern Florida. They lived north of the Santa Fe River and east of the Suwannee River, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language known as "Timucua proper". They appear to have been closely associated with the Yustaga people, who lived on the other side of the Suwannee. The Northern Utina represented one of the most powerful tribal units in the region in the 16th and 17th centuries, and may have been organized as a loose chiefdom or confederation of smaller chiefdoms. The Fig Springs archaeological site may be the remains of their principal village, Ayacuto, and the later Spanish mission of San Martín de Timucua.

The Yustaga were a Timucua people of what is now northwestern Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The westernmost Timucua group, they lived between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers in the Florida Panhandle, just east of the Apalachee people. A dominant force in regional tribal politics, they may have been organized as a loose regional chiefdom consisting of up to eight smaller local chiefdoms.

Pohoy was a chiefdom on the shores of Tampa Bay in present-day Florida in the late sixteenth century and all of the seventeenth century. Following slave-taking raids by people from the Lower Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the surviving Pohoy people lived in several locations in peninsular Florida. The Pohoy disappeared from historical accounts after 1739.

Ocale was the name of a town in Florida visited by the Hernando de Soto expedition, and of a putative chiefdom of the Timucua people. The town was probably close to the Withlacoochee River at the time of de Soto's visit, and may have later been moved to the Ocklawaha River.

San Buenaventura de Potano was a Spanish mission near Orange Lake in southern Alachua County or northern Marion County, Florida, located on the site where the town of Potano had been located when it was visited by Hernando de Soto in 1539. The Richardson/UF Village Site (8AL100), in southern Alachua County, has been proposed as the location of the town and mission.

Arapaha was a Timucua town on the Alapaha River in the 17th century. The name was also sometimes used to designate a province or sub-province in Spanish Florida.

Juan Ortiz was a Spanish sailor who was held captive and enslaved by Native Americans in Florida for eleven years, from 1528 until he was rescued by the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1539. Two accounts of Ortiz's eleven years as a captive, differing in details, offer a story of Ortiz being sentenced to death by a Native American chief two or three times, saved each time by the intervention of a daughter of the chief, and finally escaping to a neighboring chiefdom, whose chief sheltered him.

References

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, pp. 3–6.

- ↑ Hann 2003, p. 1; Tebeau 1980, p. 23; Milanich & Hudson 1993, p. 4.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, pp. 56–57, 71.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, p. 57.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, p. 72.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, p. 58.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, pp. 16, 58, 72, 74, 75–76, 84.

- ↑ Milanich & Hudson 1993, p. 76.

- ↑ Gatschet, Albert B. (1880). "The Timucua Language". Internet Archive. p. 477. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Crawford, James M. (1988). "On the Relationship of Timucua to Muskogean". In William Shipley (ed.). In Honor of Mary Haas: From the Haas Festival Conference on Native American Linguistics. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 159. ISBN 0-89925-281-8 . Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Grimes, Joseph Evans (1975). The Thread of Discourse . The Hague: Mouton. p. 159. ISBN 90-279-3164-X . Retrieved 21 November 2013.

holata timucua.

- ↑ Hann 2003, p. 5.