Related Research Articles

Arianism is a Christological doctrine considered heretical by all modern mainstream branches of Christianity. It is first attributed to Arius, a Christian presbyter who preached and studied in Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God the Father with the difference that the Son of God did not always exist but was begotten/made before time by God the Father; therefore, Jesus was not coeternal with God the Father, but nonetheless Jesus began to exist outside time.

Hilary of Poitiers was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" and the "Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or cheerful. In addition to his important work as bishop, Hilary was married and the father of Abra of Poitiers, a nun and saint who became known for her charity.

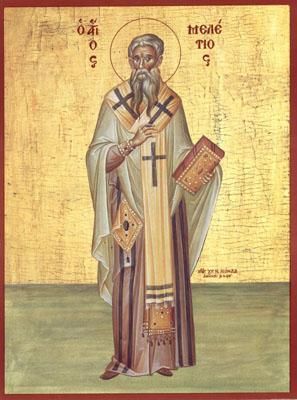

Saint Meletius was a Christian bishop of Antioch from 360 until his death in 381. However, his episcopate was dominated by a schism, usually called the Meletian schism.

Eudoxius was the eighth bishop of Constantinople from January 27, 360 to 370, previously bishop of Germanicia and of Antioch. Eudoxius was one of the most influential Arians.

The Acacians, or perhaps better described as the Homoians or Homoeans, were a non-Nicene branch of Christianity that dominated the church during much of the fourth-century Arian Controversy. They declared that the Son was similar to God the Father, without reference to substance (essence). Homoians played a major role in the Christianization of the Goths in the Danubian provinces of the Roman Empire.

In 294 AD, Sirmium was proclaimed one of four capitals of the Roman Empire. The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. In the traditional account of the Arian Controversy, the Western Church always defended the Nicene Creed. However, at the third council in 357—the most important of these councils—the Western bishops of the Christian church produced an 'Arian' Creed, known as the Second Sirmian Creed. At least two of the other councils also dealt primarily with the Arian controversy. All of these councils were held under the rule of Constantius II, who was eager to unite the church within the framework of the Eusebian Homoianism that was so influential in the east.

In 4th-century Christianity, the Anomoeans, and known also as Heterousians, Aetians, or Eunomians, were a sect that held to a form of Arianism, that Jesus Christ was not of the same nature (consubstantial) as God the Father nor was of like nature (homoiousian), as maintained by the semi-Arians.

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-eternal, and of the same substance, or consubstantial, and was therefore considered to be heretical by many contemporary Christians.

The Council of Ariminum, also known as the Council of Rimini, was an early Christian church synod in Ariminum, modern-day Rimini, in 359. Called by Roman Emperor Constantius II to resolve the Arian controversy, the Council of Ariminum for western bishops paralleled the Council of Seleucia for eastern bishops.

Aëtius of Antioch, surnamed "the Atheist" by his trinitarian enemies, founder of Anomoeanism, was a native of Coele-Syria.

The Council of Seleucia was an early Christian church synod at Seleucia Isauria.

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian disputes about the nature of Jesus Christ that began with a dispute between Arius and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies concerned the relationship between the substance of God the Father and the substance of his son.

The Pneumatomachi, also known as Macedonians or Semi-Arians in Constantinople and the Tropici in Alexandria, were an anti-Nicene Creed sect which flourished in the regions adjacent to the Hellespont during the latter half of the fourth, and the beginning of the fifth centuries. They denied the godhood of the Holy Ghost, hence the Greek name Pneumatomachi or 'Combators against the Spirit'.

Germinius, born in Cyzicus, was bishop of Sirmium, and a supporter of Homoian theology, which is often labelled as a form of Arianism.

Patrophilus was the Arian bishop of Scythopolis in the early-mid 4th century AD. He was an enemy of Athanasius who described him as a πνευματόμαχος or "fighter against the Holy Spirit". When Arius was exiled to Palestine in 323 AD, Patrophilus warmly welcomed him.

Ursacius was the bishop of Singidunum, during the middle of the 4th century. He played an important role during the evolving controversies surrounding the legacies of the Council of Nicaea and the theologian Arius, acting frequently in concert with his fellow bishops of the Diocese of Pannonia, Germinius of Sirmium and Valens of Mursa. Found at various times during their episcopal careers staking positions on both sides of the developing theological debate and internal Church politicking, Ursacius and his fellows were seen to vacillate according to the political winds.

The Diocese of Scythopolis is a titular see in Israel/Jordan and was the Metropolitan of the Roman province of Palestina II. It was centered on Modern Beth Shean (Bêsân).

Cecropius of Nicomedia was a bishop of Nicomedia and a key player in the Arian controversy.

Heortasius was a 4th-century bishop of Sardis and attendee at the Councils of Seleucia and Constantinople. He was a proto-Catholic who was sent into exile by the Semi-Arian faction following their victory at the afore-mentioned Councils.

Arian creeds are the creeds of Arian Christians, developed mostly in the fourth century when Arianism was one of the main varieties of Christianity.

References

- ↑ Sozomen, Church History, Book 2.25.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, Book 2.24.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, (The Modern Library, 1932), chap. XXI., p. 695

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 30.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 37.

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 4, chapter 10.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 37.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 37.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 37.