Ribonuclease is a type of nuclease that catalyzes the degradation of RNA into smaller components. Ribonucleases can be divided into endoribonucleases and exoribonucleases, and comprise several sub-classes within the EC 2.7 and 3.1 classes of enzymes.

Mycobacterium smegmatis is an acid-fast bacterial species in the phylum Actinomycetota and the genus Mycobacterium. It is 3.0 to 5.0 µm long with a bacillus shape and can be stained by Ziehl–Neelsen method and the auramine-rhodamine fluorescent method. It was first reported in November 1884 by Lustgarten, who found a bacillus with the staining appearance of tubercle bacilli in syphilitic chancres. Subsequent to this, Alvarez and Tavel found organisms similar to that described by Lustgarten also in normal genital secretions (smegma). This organism was later named M. smegmatis.

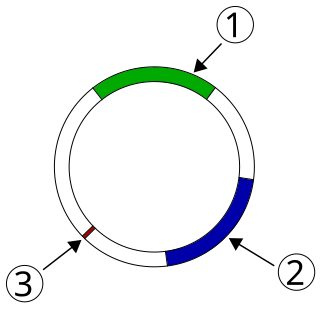

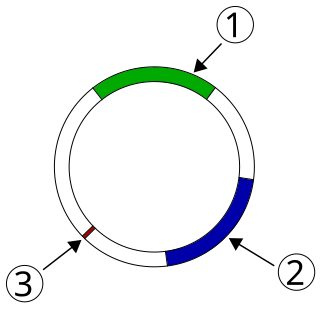

A tumour inducing (Ti) plasmid is a plasmid found in pathogenic species of Agrobacterium, including A. tumefaciens, A. rhizogenes, A. rubi and A. vitis.

A structural gene is a gene that codes for any RNA or protein product other than a regulatory factor. A term derived from the lac operon, structural genes are typically viewed as those containing sequences of DNA corresponding to the amino acids of a protein that will be produced, as long as said protein does not function to regulate gene expression. Structural gene products include enzymes and structural proteins. Also encoded by structural genes are non-coding RNAs, such as rRNAs and tRNAs.

Addiction modules are toxin-antitoxin systems. Each consists of a pair of genes that specify two components: a stable toxin and an unstable antitoxin that interferes with the lethal action of the toxin. Found first in Escherichia coli on low copy number plasmids, addiction modules are responsible for a process called the postsegregational killing effect. When bacteria lose these plasmid(s), the cured cells are selectively killed because the unstable antitoxin is degraded faster than the more stable toxin. The term "addiction" is used because the cell depends on the de novo synthesis of the antitoxin for cell survival. Thus, addiction modules are implicated in maintaining the stability of extrachromosomal elements.

A retron is a distinct DNA sequence found in the genome of many bacteria species that codes for reverse transcriptase and a unique single-stranded DNA/RNA hybrid called multicopy single-stranded DNA (msDNA). Retron msr RNA is the non-coding RNA produced by retron elements and is the immediate precursor to the synthesis of msDNA. The retron msr RNA folds into a characteristic secondary structure that contains a conserved guanosine residue at the end of a stem loop. Synthesis of DNA by the retron-encoded reverse transcriptase (RT) results in a DNA/RNA chimera which is composed of small single-stranded DNA linked to small single-stranded RNA. The RNA strand is joined to the 5′ end of the DNA chain via a 2′–5′ phosphodiester linkage that occurs from the 2′ position of the conserved internal guanosine residue.

The hok/sok system is a postsegregational killing mechanism employed by the R1 plasmid in Escherichia coli. It was the first type I toxin-antitoxin pair to be identified through characterisation of a plasmid-stabilising locus. It is a type I system because the toxin is neutralised by a complementary RNA, rather than a partnered protein.

Rhodococcus equi is a Gram-positive coccobacillus bacterium. The organism is commonly found in dry and dusty soil and can be important for diseases of domesticated animals. The frequency of infection can reach near 60%. R. equi is an important pathogen causing pneumonia in foals. Since 2008, R. equi has been known to infect wild boar and domestic pigs. R. equi can infect humans. At-risk groups are immunocompromised people, such as HIV-AIDS patients or transplant recipients. Rhodococcus infection in these patients resemble clinical and pathological signs of pulmonary tuberculosis. It is facultative intracellular.

In a screen of the Bacillus subtilis genome for genes encoding ncRNAs, Saito et al. focused on 123 intergenic regions (IGRs) over 500 base pairs in length, the authors analyzed expression from these regions. Seven IGRs termed bsrC, bsrD, bsrE, bsrF, bsrG, bsrH and bsrI expressed RNAs smaller than 380 nt. All the small RNAs except BsrD RNA were expressed in transformed Escherichia coli cells harboring a plasmid with PCR-amplified IGRs of B. subtilis, indicating that their own promoters independently express small RNAs. Under non-stressed condition, depletion of the genes for the small RNAs did not affect growth. Although their functions are unknown, gene expression profiles at several time points showed that most of the genes except for bsrD were expressed during the vegetative phase, but undetectable during the stationary phase. Mapping the 5' ends of the 6 small RNAs revealed that the genes for BsrE, BsrF, BsrG, BsrH, and BsrI RNAs are preceded by a recognition site for RNA polymerase sigma factor σA.

PtaRNA1 is a family of non-coding RNAs. Homologs of PtaRNA1 can be found in the bacterial families, Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. In all cases the PtaRNA1 is located anti-sense to a short protein-coding gene. In Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, this gene is annotated as XCV2162 and is included in the plasmid toxin family of proteins.

Bacterial small RNAs (bsRNA) are small RNAs produced by bacteria; they are 50- to 500-nucleotide non-coding RNA molecules, highly structured and containing several stem-loops. Numerous sRNAs have been identified using both computational analysis and laboratory-based techniques such as Northern blotting, microarrays and RNA-Seq in a number of bacterial species including Escherichia coli, the model pathogen Salmonella, the nitrogen-fixing alphaproteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti, marine cyanobacteria, Francisella tularensis, Streptococcus pyogenes, the pathogen Staphylococcus aureus, and the plant pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae. Bacterial sRNAs affect how genes are expressed within bacterial cells via interaction with mRNA or protein, and thus can affect a variety of bacterial functions like metabolism, virulence, environmental stress response, and structure.

The TisB-IstR toxin-antitoxin system is the first known toxin-antitoxin system which is induced by the SOS response in response to DNA damage.

A toxin-antitoxin system consists of a "toxin" and a corresponding "antitoxin", usually encoded by closely linked genes. The toxin is usually a protein while the antitoxin can be a protein or an RNA. Toxin-antitoxin systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes, and organisms often have them in multiple copies. When these systems are contained on plasmids – transferable genetic elements – they ensure that only the daughter cells that inherit the plasmid survive after cell division. If the plasmid is absent in a daughter cell, the unstable antitoxin is degraded and the stable toxic protein kills the new cell; this is known as 'post-segregational killing' (PSK).

Plasmid-mediated resistance is the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes which are carried on plasmids. Plasmids possess mechanisms that ensure their independent replication as well as those that regulate their replication number and guarantee stable inheritance during cell division. By the conjugation process, they can stimulate lateral transfer between bacteria from various genera and kingdoms. Numerous plasmids contain addiction-inducing systems that are typically based on toxin-antitoxin factors and capable of killing daughter cells that don't inherit the plasmid during cell division. Plasmids often carry multiple antibiotic resistance genes, contributing to the spread of multidrug-resistance (MDR). Antibiotic resistance mediated by MDR plasmids severely limits the treatment options for the infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria, especially family Enterobacteriaceae. The global spread of MDR plasmids has been enhanced by selective pressure from antimicrobial medications used in medical facilities and when raising animals for food.

The SymE-SymR toxin-antitoxin system consists of a small symbiotic endonuclease toxin, SymE, and a non-coding RNA symbiotic RNA antitoxin, SymR, which inhibits SymE translation. SymE-SymR is a type I toxin-antitoxin system, and is under regulation by the antitoxin, SymR. The SymE-SymR complex is believed to play an important role in recycling damaged RNA and DNA. The relationship and corresponding structures of SymE and SymR provide insight into the mechanism of toxicity and overall role in prokaryotic systems.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis contains at least nine small RNA families in its genome. The small RNA (sRNA) families were identified through RNomics – the direct analysis of RNA molecules isolated from cultures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The sRNAs were characterised through RACE mapping and Northern blot experiments. Secondary structures of the sRNAs were predicted using Mfold.

The TxpA/RatA toxin-antitoxin system was first identified in Bacillus subtilis. It consists of a non-coding 222nt sRNA called RatA and a protein toxin named TxpA.

Escherichia coli contains a number of small RNAs located in intergenic regions of its genome. The presence of at least 55 of these has been verified experimentally. 275 potential sRNA-encoding loci were identified computationally using the QRNA program. These loci will include false positives, so the number of sRNA genes in E. coli is likely to be less than 275. A computational screen based on promoter sequences recognised by the sigma factor sigma 70 and on Rho-independent terminators predicted 24 putative sRNA genes, 14 of these were verified experimentally by northern blotting. The experimentally verified sRNAs included the well characterised sRNAs RprA and RyhB. Many of the sRNAs identified in this screen, including RprA, RyhB, SraB and SraL, are only expressed in the stationary phase of bacterial cell growth. A screen for sRNA genes based on homology to Salmonella and Klebsiella identified 59 candidate sRNA genes. From this set of candidate genes, microarray analysis and northern blotting confirmed the existence of 17 previously undescribed sRNAs, many of which bind to the chaperone protein Hfq and regulate the translation of RpoS. UptR sRNA transcribed from the uptR gene is implicated in suppressing extracytoplasmic toxicity by reducing the amount of membrane-bound toxic hybrid protein.

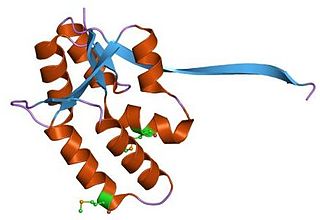

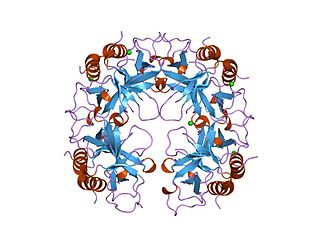

In molecular biology the PIN domain is a protein domain that is about 130 amino acids in length. PIN domains function as nuclease enzymes that cleave single stranded RNA in a sequence- or structure-dependent manner.

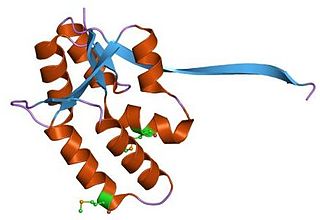

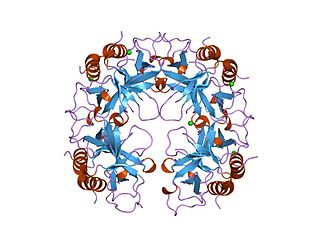

The CcdA/CcdB Type II Toxin-antitoxin system is one example of the bacterial toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems that encode two proteins, one a potent inhibitor of cell proliferation (toxin) and the other its specific antidote (antitoxin). These systems preferentially guarantee growth of plasmid-carrying daughter cells in a bacterial population by killing newborn bacteria that have not inherited a plasmid copy at cell division.