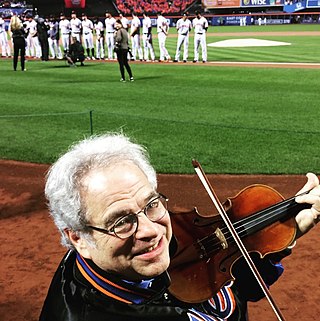

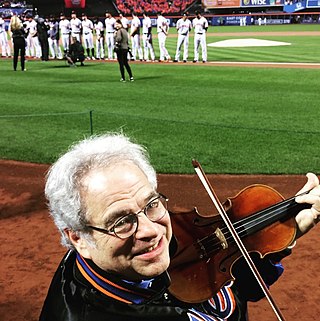

Itzhak Perlman is an Israeli-American violinist. He has performed worldwide and throughout the United States, in venues that have included a state dinner for Elizabeth II at the White House in 2007, and at the 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama. He has conducted the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Westchester Philharmonic. In 2015, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Perlman has won 16 Grammy Awards, including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and four Emmy Awards.

The Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, was composed by Johannes Brahms in 1878 and dedicated to his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. It is Brahms's only violin concerto, and, according to Joachim, one of the four great German violin concerti:

The Germans have four violin concertos. The greatest, most uncompromising is Beethoven's. The one by Brahms vies with it in seriousness. The richest, the most seductive, was written by Max Bruch. But the most inward, the heart's jewel, is Mendelssohn's.

Leopold von Auer was a Hungarian violinist, academic, conductor, composer, and instructor. Many of his students went on to become prominent concert performers and teachers.

Felix Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64, MWV O 14, is his last concerto. Well received at its premiere, it has remained among the most prominent and highly-regarded violin concertos. It holds a central place in the violin repertoire and has developed a reputation as an essential concerto for all aspiring concert violinists to master, and usually one of the first Romantic era concertos they learn. A typical performance lasts just under half an hour.

Sergei Prokofiev began his Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 19, as a concertino in 1915 but soon abandoned it to work on his opera The Gambler. He returned to the concerto in the summer of 1917. It was premiered on October 18, 1923 at the Paris Opera with Marcel Darrieux playing the violin part and the Paris Opera Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. Igor Stravinsky made his debut as conductor at the same concert, conducting the first performance of his own Octet for Wind Instruments.

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B♭ minor, Op. 23, was composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky between November 1874 and February 1875. It was revised in 1879 and in 1888. It was first performed on October 25, 1875, in Boston by Hans von Bülow after Tchaikovsky's desired pianist, Nikolai Rubinstein, criticised the piece. Rubinstein later withdrew his criticism and became a fervent champion of the work. It is one of the most popular of Tchaikovsky's compositions and among the best known of all piano concerti.

Ilya Kaler is a Russian-born violinist. Born and educated in Moscow, Kaler is the only person to have won Gold Medals at all three of the International Tchaikovsky Competition ; the Sibelius ; and the Paganini.

ZinoVinnikov is a Russian-Dutch violinist and one of the leading representatives of the St Petersburg violin tradition.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 44, was written in 1879–1880 and dedicated to Nikolai Rubinstein, who had insisted he perform it at the premiere as a way of making up for his harsh criticism of Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto. But Rubinstein never played it, as he died in March 1881, and the work has never attained much popularity.

The Cello Concerto of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is a conjectural work based in part on a 60-bar fragment found on the back of the rough draft for the last movement of the composer's Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique. In 2006, Ukrainian composer and cellist Yuriy Leonovich completed the work.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E-flat major was at first conceived by him as a symphony in the same key. But he abandoned that idea, jetisoned all but the planned first movement, and reworked this in 1893 as a one-movement Allegro brillante for piano and orchestra. His last completed work, it was duly published as Opus 75 the next year, after he died, but given by publisher Jurgenson the title "Concerto No. 3 pour Piano avec accompagnement d'Orchestre".

The Concert Fantasia in G, Op. 56, for piano and orchestra, was written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky between June and October 1884. It was premiered in Moscow on 6 March [O.S. 22 February] 1885, with Sergei Taneyev as soloist and Max Erdmannsdörfer conducting. The Concert Fantasia received many performances in the first 20 years of its existence. It then disappeared from the repertoire and lay virtually unperformed for many years, but underwent a revival in the latter part of the 20th century.

Wilhelm Karl Friedrich Fitzenhagen was a German cellist, composer and teacher, best known today as the dedicatee of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Variations on a Rococo Theme.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was a Russian composer especially known for three very popular ballets: Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. He also composed operas, symphonies, choral works, concertos, and various other classical works. His work became dominant in 19th century Russia, and he became known both in and outside Russia as its greatest musical talent.

Iosif Iosifovich Kotek, also seen as Josef or Yosif, was a Russian violinist and composer remembered for his association with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. He assisted Tchaikovsky with technical difficulties in the writing of the solo part in his Violin Concerto in D.

The Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33, for cello and orchestra was the closest Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ever came to writing a full concerto for cello and orchestra. The style was inspired by Mozart, Tchaikovsky's role model, and makes it clear that Tchaikovsky admired the Classical style very much. However, the Theme is not Rococo in origin, but actually an original theme in the Rococo style.

The Sérénade mélancolique in B-flat minor for violin and orchestra, Op. 26, was written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in February 1875. It was his first work for violin and orchestra, and was written immediately after completing the Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor.

The Valse-Scherzo in C major, Op. 34, TH 58, is a work for violin and orchestra by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, written in 1877.

The Concerto for Piano, Violin, and Strings in D minor, MWV O4, also known as the Double Concerto in D minor, was written in 1823 by Felix Mendelssohn when he was 14 years old. This piece is Mendelssohn's fourth work for a solo instrument with orchestral accompaniment, preceded by a Largo and Allegro in D minor for Piano and Strings MWV O1, the Piano Concerto in A Minor MWV O2, and the Violin Concerto in D minor MWV O3. Mendelssohn composed the work to be performed for a private concert on May 25, 1823 at the Mendelssohn home in Berlin with his violin teacher and friend, Eduard Rietz. Following this private performance, Mendelssohn revised the scoring, adding winds and timpani and is possibly the first work in which Mendelssohn used winds and timpani in a large work. A public performance was given on July 3, 1823 at the Berlin Schauspielhaus. Like the A minor piano concerto (1822), it remained unpublished during Mendelssohn's lifetime and it wasn't until 1999 when a critical edition of the piece was available.