In music, especially Schenkerian analysis, a voice exchange (German : Stimmtausch; also called voice interchange) is the repetition of a contrapuntal passage with the voices' parts exchanged; for instance, the melody of one part appears in a second part and vice versa. It differs from invertible counterpoint in that there is no octave displacement; therefore it always involves some voice crossing. If scored for equal instruments or voices, it may be indistinguishable from a repeat, although because a repeat does not appear in any of the parts, it may make the music more interesting for the musicians. [1] It is a characteristic feature of rounds, although not usually called such. [2]

Patterns of voice exchange are sometimes schematized using letters for melodic patterns. [3] A double voice exchange has the pattern:

Voice 1: a b Voice 2: b a

A triple exchange would thus be written:

Voice 1: a b c Voice 2: c a b Voice 3: b c a

The first use of the term "Stimmtausch" was in 1903-4 in an article by Friedrich Ludwig, while its English calque was first used in 1949 by Jacques Handschin. [4] The term is also used, with a related but distinct meaning, in Schenkerian theory.

"When a piece is entirely conceived according to the system of Stimmtausch, it belongs to the rondellus type." [5]

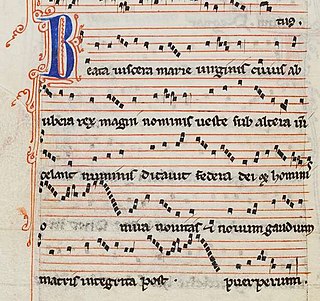

Voice exchange appeared in the 12th-century repertory of the Saint Martial school as a consequence of imitation. [6] Voice exchange first became common in the Notre Dame school, who used both double and triple exchanges in organa and conductus (in particular the wordless caudae). [3] [7] In fact, Richard Hoppin regarded voice exchange as "the basic device from which the Notre Dame composers evolved ways of organizing and integrating the simultaneous melodies of polyphony," [8] and of considerable importance as a means of symmetry and design in polyphonic music as well as starting point for more complex contrapuntal devices. [6] The importance was not lost on theorists of the time, either, as Johannes de Garlandia gave an example, which he called "repetitio diverse vocis," and noted in "three- and four-part organa, and conductus, and in many other things." [4]

In Pérotin's four-part organum "Sederunt principes", sections that are exchanged vary considerably in length, from two to more than ten measures, [1] and parts that are exchanged are sometimes nested (i.e. there is a brief voice exchange among two parts within a larger section which subsequently is repeated using a voice exchange). [9] The elaborate patterns of voice exchange in pieces like "Sederunt" prove that Perotin composed them as a whole, not by successively adding voices. [8]

In the 13th century, the technique was used by English composers of the Worcester school as a structural device. [2] In the genre rondellus, as described by the theorist Walter Odington (c. 1300), the central part of the piece was based entirely on voice exchange. Ordinarily, but not always, the text is exchanged along with the melody. [10] It also appears in the lower parts (pes) of "Sumer Is Icumen In", while the upper parts always include a new melodic phrase instead of a true voice exchange. [11]

Voice exchange gradually died out after 1300, due to the gradual separation of voice ranges and the expansion of the ambitus of a composition. [4] However, it occasionally made limited appearances in simple polyphony of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and was, for example, common in the upper parts of Baroque trio sonatas. [2]

Voice exchange is also used in Schenkerian analysis to refer to a pitch class exchange involving two voices across registers, one of which is usually the bass. In this sense, it is a common secondary structural feature found in the music of a wide variety of composers. [12] In analyses, this is represented by two crossing lines with double arrowheads indicating the exchanged pitches. A common exchange of this sort involves a progression of a third using a passing tone, the exchange notated by the interval succession 10-8-6 (if this is with the bass, the third chord is a first inversion of the first). This is in effect a prolongation of the third (generally as part of a triad), a preservation of the harmony across a time span. [13] Another type of exchange has the interval succession 10-10-6-6 (or 6-6-10-10) and involves a pair of notes exchanged across parts. [14]

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and followed by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period. Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music can be divided into Early (500–1150), High (1000–1300), and Late (1300–1400) medieval music.

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries, with later additions and redactions. Although popular legend credits Pope Gregory I with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that it arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of the Old Roman chant and Gallican chant.

Pérotin was a composer associated with the Notre Dame school of polyphony in Paris and the broader ars antiqua musical style of high medieval music. He is credited with developing the polyphonic practices of his predecessor Léonin, with the introduction of three and four-part harmonies.

Organum is, in general, a plainchant melody with at least one added voice to enhance the harmony, developed in the Middle Ages. Depending on the mode and form of the chant, a supporting bass line may be sung on the same text, the melody may be followed in parallel motion, or a combination of both of these techniques may be employed. As no real independent second voice exists, this is a form of heterophony. In its earliest stages, organum involved two musical voices: a Gregorian chant melody, and the same melody transposed by a consonant interval, usually a perfect fifth or fourth. In these cases the composition often began and ended on a unison, the added voice keeping to the initial tone until the first part has reached a fifth or fourth, from where both voices proceeded in parallel harmony, with the reverse process at the end. Organum was originally improvised; while one singer performed a notated melody, another singer—singing "by ear"—provided the unnotated second melody. Over time, composers began to write added parts that were not just simple transpositions, thus creating true polyphony.

In music, texture is how the tempo, melodic, and harmonic materials are combined in a musical composition, determining the overall quality of the sound in a piece. The texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices. For example, a thick texture contains many 'layers' of instruments. One of these layers could be a string section or another brass. The thickness also is changed by the amount and the richness of the instruments playing the piece. The thickness varies from light to thick. A piece's texture may be changed by the number and character of parts playing at once, the timbre of the instruments or voices playing these parts and the harmony, tempo, and rhythms used. The types categorized by number and relationship of parts are analyzed and determined through the labeling of primary textural elements: primary melody (PM), secondary melody (SM), parallel supporting melody (PSM), static support (SS), harmonic support (HS), rhythmic support (RS), and harmonic and rhythmic support (HRS).

The Florentine Camerata, also known as the Camerata de' Bardi, were a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de' Bardi to discuss and guide trends in the arts, especially music and drama. They met at the house of Giovanni de' Bardi, and their gatherings had the reputation of having all the most famous men of Florence as frequent guests. After first meeting in 1573, the activity of the Camerata reached its height between 1577 and 1582. While propounding a revival of the Greek dramatic style, the Camerata's musical experiments led to the development of the stile recitativo. In this way it facilitated the composition of dramatic music and the development of opera.

The Notre-Dame school or the Notre-Dame school of polyphony refers to the group of composers working at or near the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris from about 1160 to 1250, along with the music they produced.

Anonymous IV is the designation given to the writer of an important treatise of medieval music theory. He was probably an English student working at Notre Dame de Paris, most likely in the 1270s or 1280s. Nothing is known about his life. His writings survive in two partial copies from Bury St Edmunds; one from the 13th century, and one from the 14th.

The conductus was a sacred Latin song in the Middle Ages, one whose poetry and music were newly composed. It is non-liturgical since its Latin lyric borrows little from previous chants. The conductus was northern French equivalent of the versus, which flourished in Aquitaine. It was originally found in the twelfth-century Aquitanian repertories. But major collections of conducti were preserved in Paris. The conductus typically includes one, two, or three voices. A small number of the conducti are for four voices. Stylistically, the conductus is a type of discant. Its form can be strophic or through-composed form. The genre flourished from the early twelfth century to the middle of thirteenth century. It was one of the principal types of vocal composition of the ars antiqua period of medieval music history.

Voice leading is the linear progression of individual melodic lines and their interaction with one another to create harmonies, typically in accordance with the principles of common-practice harmony and counterpoint.

The gradual is a chant or hymn in the Mass, the liturgical celebration of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, and among some other Christians. It gets its name from the Latin gradus because it was once chanted on the step of the ambo or altar. In the Tridentine Mass, it is sung after the reading or chanting of the epistle and before the Alleluia, or, during penitential seasons, before the tract. In the Mass of Paul VI, the gradual is usually replaced with the responsorial psalm. Although the Gradual remains an option in the Mass of Paul VI, its use is extremely rare outside monasteries. The gradual is part of the proper of the Mass.

In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations. The value of each note is not determined by the form of the written note, but rather by its position within a group of notes written as a single figure called a ligature, and by the position of the ligature relative to other ligatures. Modal notation was developed by the composers of the Notre Dame school from 1170 to 1250, replacing the even and unmeasured rhythm of early polyphony and plainchant with patterns based on the metric feet of classical poetry, and was the first step towards the development of modern mensural notation. The rhythmic modes of Notre Dame Polyphony were the first coherent system of rhythmic notation developed in Western music since antiquity.

In Western music and music theory, augmentation is the lengthening of a note or the widening of an interval.

A descant, discant, or discantus is any of several different things in music, depending on the period in question; etymologically, the word means a voice (cantus) above or removed from others. The Harvard Dictionary of Music states:

Anglicized form of L. discantus and a variant of discant. Throughout the Middle Ages the term was used indiscriminately with other terms, such as descant. In the 17th century it took on special connotations in instrumental practice.

The Bamberg Codex is a manuscript containing two treatises on music theory and a large body of 13th-century French polyphony.

Daseian notation is the type of musical notation used in the ninth century anonymous musical treatises Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis. The music of the Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, written in Daseian notation, are the earliest known examples of written polyphonic music in history.

In music, voice crossing is the intersection of melodic lines in a composition, leaving a lower voice on a higher pitch than a higher voice. Because this can cause registral confusion and reduce the independence of the voices, it is sometimes avoided in composition and pedagogical exercises.

In Schenkerian analysis, unfolding or compound melody is the implication of more than one melody or line by a single voice through skipping back and forth between the notes of the two melodies. In music cognition, the phenomenon is also known as melodic fission.

In music cognition, melodic fission, is a phenomenon in which one line of pitches is heard as two or more separate melodic lines. This occurs when a phrase contains groups of pitches at two or more distinct registers or with two or more distinct timbres.

This is a glossary of Schenkerian analysis, a method of musical analysis of tonal music based on the theories of Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935). The method is discussed in the concerned article and no attempt is made here to summarize it. Similarly, the entries below whenever possible link to other articles where the concepts are described with more details, and the definitions are kept here to a minimum.