This article needs additional citations for verification .(June 2015) |

Wolfgang Krege (born 1 February 1939, Berlin; died 13 April 2005, Stuttgart) was a German author and translator.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(June 2015) |

Wolfgang Krege (born 1 February 1939, Berlin; died 13 April 2005, Stuttgart) was a German author and translator.

Wolfgang Krege was born and raised in Berlin. In the early 1960s he began studying philosophy at the Free University of Berlin. Afterwards he worked as editor of lexica, as copywriter and editor for publishing houses. In the 1970s he started translating texts, initially focusing on non-fiction.

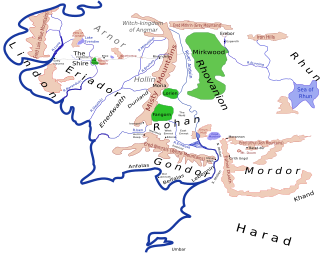

He gained a greater readership by his translation of J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Silmarillion . In the 1990s he retranslated The Hobbit ; compared to the earlier translation by Walter Scherf, who had left out or shortened most of the poems and songs embedded into the plot, and which moreover contained illustrations by children's books illustrator Klaus Ensikat, Krege's version rather appeals to a more grown-up readership.[ citation needed ] Another difference is made by a lack of adherence to the original: Krege has a tendency to write a funnier and fancier book than the original Hobbit.[ according to whom? ] Thereby various sentences are interpreted in a way which cannot any more be regarded as translation but is clearly new script. Additionally, Krege's version features a number of modern words like "Hurricane" which can easily be seen atypical for the medievally and European inspired Middle-earth (although Tolkien's original as well does contain words like "football" or "express train"). Krege's translation of place names though is closer to the original script. Where "Rivendell" remained untranslated by Scherf, Krege used Bruchtal and standardised the place names according to the German translation of The Lord of the Rings by Margaret Carroux and E.-M. von Freymann (Klett-Cotta 1969/1970). He also eradicated earlier misinterpretations of English "Elf" to German "Fee" (fairy), where Tolkien explicitly wished to distinguish his elves from the diminutive airy-winged fairies. [1]

Krege's retranslation of The Lord of the Rings (Ger.: Der Herr der Ringe) is highly disputed among fans. [2] The new German interpretation of 2002 tries stronger than the old Carroux version to reflect the different style of speech employed by the various characters in the book. In the old German translation the speech is quite uniform throughout the plot – moderately old-fashioned and according to some critics[ who? ] even artificially folksy. The English original though features various layers of speech, from a 16th-century Bible style to the rustic and urban, sometimes gross, common British English of the 1940s, i.e. the time of its being written. Krege tries to imitate this in German, but used the German language of the 1990s as a reference rather than the 1940s. For example, he translated Samwise Gamgee's often-employed phrase "Master Frodo" to "Chef" (German (and French): boss; not to be confused with English "master cook") - a term which many fans of classic fantasy literature in German-speaking countries think of as totally improper. In Wolfgang Krege's translation, the appendices to The Lord of the Rings are for the first time completely translated to German, save for one part.

Krege wrote also an (equally disputed) retranslation of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange as well as other works by Burgess. In addition, Krege was the standard translator to German for works by Amélie Nothomb.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was an English writer, poet, philologist, and academic, best known as the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Christopher John Reuel Tolkien was an English and French academic editor. He was the son of author J. R. R. Tolkien and the editor of much of his father's posthumously published work. Tolkien drew the original maps for his father's The Lord of the Rings.

In the fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Dwarves are a race inhabiting Middle-earth, the central continent of Arda in an imagined mythological past. They are based on the dwarfs of Germanic myths: small humanoids that dwell in mountains, associated with mining, metallurgy, blacksmithing and jewellery.

Ungoliant(Sindarin pronunciation: ) is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, described as an evil spirit in the form of a spider. She is mentioned briefly in The Lord of the Rings, and plays a supporting role in The Silmarillion. Her origins are unclear, as Tolkien's writings do not explicitly reveal her nature, other than that she is from "before the world". She is one of a few instances, along with Tom Bombadil and the Cats of Queen Berúthiel, where Tolkien does not provide a clear background for an element of his fiction.

Trolls are fictional characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, and feature in films and games adapted from his novels. They are portrayed as monstrously large humanoids of great strength and poor intellect. In The Hobbit, like the dwarf Alviss of Norse mythology, they must be below ground before dawn or turn to stone, whereas in The Lord of the Rings they are able to face daylight.

The term Middle-earth canon, also called Tolkien's canon, is used for the published writings of J. R. R. Tolkien regarding Middle-earth as a whole. The term is also used in Tolkien fandom to promote, discuss and debate the idea of a consistent fictional canon within a given subset of Tolkien's writings.

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien have served as the inspiration to painters, musicians, film-makers and writers, to such an extent that he is sometimes seen as the "father" of the entire genre of high fantasy.

Do not laugh! But once upon a time I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic to the level of romantic fairy-story... The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd.

Weapons and armour of Middle-earth are those of J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy writings, such as The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

Anke Katrin Eißmann is a German illustrator and graphic designer known for her illustrations of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. She studied visual communication at Bauhaus University in Weimar and at the Colchester Institute in the United Kingdom. Eißmann has also made a number of short films. She is an art teacher at the Johanneum high school in Herborn.

Robert Spaemann was a German Catholic philosopher. He is considered a member of the Ritter School.

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his The Lord of the Rings, and which his son Christopher Tolkien summarized in his compilation of The Silmarillion and documented in his 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth. The legendarium's origins date back to 1914, when he began writing poems and story sketches, drawing maps, and inventing languages and names as a private project to create a unique English mythology. The earliest story drafts are from 1916; he revised and rewrote these for most of his adult life.

J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy books on Middle-earth, especially The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, drew on a wide array of influences including language, Christianity, mythology, archaeology, ancient and modern literature, and personal experience. He was inspired primarily by his profession, philology; his work centred on the study of Old English literature, especially Beowulf, and he acknowledged its importance to his writings.

The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, written originally in English, has since been translated, with varying degrees of success, into dozens of other languages. Tolkien, an expert in Germanic philology, scrutinized those that were under preparation during his lifetime, and made comments on early translations that reflect both the translation process and his work. To aid translators, and because he was unhappy with some choices made by early translators such as Åke Ohlmarks, Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings in 1967.

Mirkwood is a name used for a great dark fictional forest in novels by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris in the 19th century, and by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 20th century. The critic Tom Shippey explains that the name evoked the excitement of the wildness of Europe's ancient North.

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the human-inhabited world, that is, the central continent of the Earth, in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology is a scholarly study of the Middle-earth works of J. R. R. Tolkien written by Tom Shippey and first published in 1982. The book discusses Tolkien's philology, and then examines in turn the origins of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and his minor works. An appendix discusses Tolkien's many sources. Two further editions extended and updated the work, including a discussion of Peter Jackson's film version of The Lord of the Rings.

The Silmarillion is a collection of mythopoeic stories by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien, edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977 with assistance from the fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay. The Silmarillion tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the once-great region of Beleriand, the sunken island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—take place. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher Stanley Unwin requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the stories that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

The Annotated Hobbit: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again is an edition of J. R. R. Tolkien's novel The Hobbit with a commentary by Douglas A. Anderson. It was first published in 1988 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first American publication of The Hobbit, and by Unwin Hyman of London.

Sven Felix Kellerhoff is a German historian, journalist and author who specialises in the history of the Nazi era.

The music of Middle-earth consists of the music mentioned by J. R. R. Tolkien in his Middle-earth books, the music written by other artists to accompany performances of his work, whether individual songs or adaptations of his books for theatre, film, radio, and games, and music more generally inspired by his books.

For the audio book the intensively discussed translation by Wolfgang Krege was used (Für das Hörbuch wurde die intensiv diskutierte Übersetzung von Wolfgang Krege verwendet.)