The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At 508 million years old, it is one of the earliest fossil beds containing soft-part imprints.

Stephen Jay Gould was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In 1996, Gould was hired as the Vincent Astor Visiting Research Professor of Biology at New York University, after which he divided his time teaching between there and Harvard.

Lobopodians are members of the informal group Lobopodia, or the formally erected phylum Lobopoda Cavalier-Smith (1998). They are panarthropods with stubby legs called lobopods, a term which may also be used as a common name of this group as well. While the definition of lobopodians may differ between literatures, it usually refers to a group of soft-bodied, marine worm-like fossil panarthropods such as Aysheaia and Hallucigenia. However, other genera like Kerygmachela and Pambdelurion are often referred to as “gilled lobopodians”.

Hallucigenia is a genus of lobopodian known from Cambrian aged fossils in Burgess Shale-type deposits in Canada and China, and from isolated spines around the world. The generic name reflects the type species' unusual appearance and eccentric history of study; when it was erected as a genus, H. sparsa was reconstructed as an enigmatic animal upside down and back to front. Lobopodians are a grade of Paleozoic panarthropods from which the velvet worms, water bears, and arthropods arose.

The Maotianshan Shales (帽天山页岩) are a series of Early Cambrian sedimentary deposits in the Chiungchussu Formation, famous for their Konservat Lagerstätten, deposits known for the exceptional preservation of fossilized organisms or traces. The Maotianshan Shales form one of some forty Cambrian fossil locations worldwide exhibiting exquisite preservation of rarely preserved, non-mineralized soft tissue, comparable to the fossils of the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada. They take their name from Maotianshan Hill in Chengjiang County, Yunnan Province, China.

Opabinia regalis is an extinct, stem group arthropod found in the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale Lagerstätte of British Columbia. Opabinia was a soft-bodied animal, measuring up to 7 cm in body length, and its segmented trunk had flaps along the sides and a fan-shaped tail. The head shows unusual features: five eyes, a mouth under the head and facing backwards, and a clawed proboscis that probably passed food to the mouth. Opabinia probably lived on the seafloor, using the proboscis to seek out small, soft food. Fewer than twenty good specimens have been described; 3 specimens of Opabinia are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they constitute less than 0.1% of the community.

Marrella is an extinct genus of marrellomorph arthropod known from the Middle Cambrian of North America and Asia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada, with tens of thousands of specimens collected. Much rarer remains are also known from deposits in China.

Charles Doolittle Walcott was an American paleontologist, administrator of the Smithsonian Institution from 1907 to 1927, and director of the United States Geological Survey. He is famous for his discovery in 1909 of well-preserved fossils, including some of the oldest soft-part imprints, in the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada.

Pikaia gracilens is an extinct, primitive chordate animal known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. Described in 1911 by Charles Doolittle Walcott as an annelid, and in 1979 by Harry B. Whittington and Simon Conway Morris as a chordate, it became "the most famous early chordate fossil", or "famously known as the earliest described Cambrian chordate". It is estimated to have lived during the latter period of the Cambrian explosion. Since its initial discovery, more than a hundred specimens have been recovered.

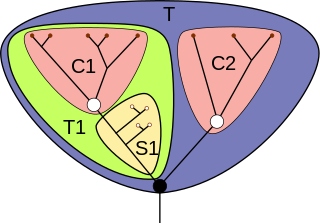

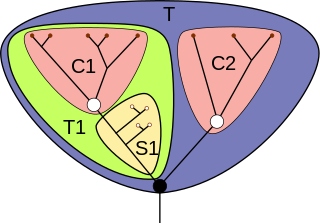

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. It is thus a way of defining a clade, a group consisting of a species and all its extant or extinct descendants. For example, Neornithes (birds) can be defined as a crown group, which includes the most recent common ancestor of all modern birds, and all of its extant or extinct descendants.

Simon Conway Morris is an English palaeontologist, evolutionary biologist, and astrobiologist known for his study of the fossils of the Burgess Shale and the Cambrian explosion. The results of these discoveries were celebrated in Stephen Jay Gould's 1989 book Wonderful Life. Conway Morris's own book on the subject, The Crucible of Creation (1998), however, is critical of Gould's presentation and interpretation.

Helmetia is an extinct genus of arthropod from the middle Cambrian. Its fossils have been found in the Burgess Shale of Canada and the Jince Formation of the Czech Republic.

A number of assemblages bear fossil assemblages similar in character to that of the Burgess Shale. While many are also preserved in a similar fashion to the Burgess Shale, the term "Burgess Shale-type fauna" covers assemblages based on taxonomic criteria only.

The fossils of the Burgess Shale, like the Burgess Shale itself, are fossils that formed around 505 million years ago in the mid-Cambrian period. They were discovered in Canada in 1886, and Charles Doolittle Walcott collected over 65,000 specimens in a series of field trips up to the alpine site from 1909 to 1924. After a period of neglect from the 1930s to the early 1960s, new excavations and re-examinations of Walcott's collection continue to reveal new species, and statistical analysis suggests that additional discoveries will continue for the foreseeable future. Stephen Jay Gould's 1989 book Wonderful Life describes the history of discovery up to the early 1980s, although his analysis of the implications for evolution has been contested.

Vetulicola cuneata is a species of extinct animal from the Early Cambrian Chengjiang biota of China. It was described by Hou Xian-guang in 1987 from the Lower Cambrian Chiungchussu Formation, and became the first animal under an eponymous phylum Vetulicolia.

Opabiniidae is an extinct family of marine stem-arthropods. Its type and best-known genus is Opabinia. It also contains Utaurora, and Mieridduryn. Opabiniids closely resemble radiodonts, but their frontal appendages were basally fused into a proboscis. Opabiniids also distinguishable from radiodonts by setal blades covering at least part of the body flaps and serrated caudal rami.

In evolutionary biology, contingency describes how the outcome of evolution may be affected by the history of a particular lineage.

Hallucigeniidae is a family of extinct worms belonging to the group Lobopodia that originated during the Cambrian explosion. It is based on the species Hallucigenia sparsa, the fossil of which was discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911 from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia. The name Hallucigenia was created by Simon Conway Morris in 1977, from which the family was erected after discoveries of other hallucigeniid worms from other parts of the world. Classification of these lobopods and their relatives are still controversial, and the family consists of at least four genera.

The Cambrian chordates are an extinct group of animals belonging to the phylum Chordata that lived during the Cambrian, between 538 and 485 million years ago. The first Cambrian chordate known is Pikaia gracilens, a lancelet-like animal from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada. The discoverer, Charles Doolittle Walcott, described it as a kind of worm (annelid) in 1911, but it was later identified as a chordate. Subsequent discoveries of other Cambrian fossils from the Burgess Shale in 1991, and from the Chengjiang biota of China in 1991, which were later found to be of chordates, several Cambrian chordates are known, with some fossils considered as putative chordates.

Hou Xian-guang is a Chinese paleontologist at Yunnan University who made key discoveries in the Cambrian life of China around 518 myr. His first discovery of animal fossils from the Cambrian sediments at Chengjiang County, Yunnan Province, led to the establishment of the Chengjiang biota, an assemblage of various life forms during the Cambrian Period. The discovery of the Chengjiang biota, remarked as "among the most spectacular in this [20th] century", added to the better understanding of how animal forms originated and evolved during the so-called Cambrian explosion.