Babylonia was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia. It emerged as an Akkadian populated but Amorite-ruled state c. 1894 BC. During the reign of Hammurabi and afterwards, Babylonia was retrospectively called "the country of Akkad", a deliberate archaism in reference to the previous glory of the Akkadian Empire. It was often involved in rivalry with the older ethno-linguistically related state of Assyria in the north of Mesopotamia and Elam to the east in Ancient Iran. Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire, Third Dynasty of Ur, and Old Assyrian Empire. The Babylonian Empire rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom centered around the city of Babylon.

Nergal was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations indicating that his cult survived into the period of Achaemenid domination. He was primarily associated with war, death, and disease, and has been described as the "god of inflicted death". He reigned over Kur, the Mesopotamian underworld, depending on the myth either on behalf of his parents Enlil and Ninlil, or in later periods as a result of his marriage with the goddess Ereshkigal. Originally either Mammitum, a goddess possibly connected to frost, or Laṣ, sometimes assumed to be a minor medicine goddess, were regarded as his wife, though other traditions existed, too.

Marduk is a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon who eventually rose to power in the First Millennium BC. In the city of Babylon, Marduk was worshipped in the temple Esagila. His symbol is the spade and he is associated with the Mušḫuššu.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic itself represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate, but exclude the religions of "non-Semitic" speakers of the region such as Egyptians, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Urartians, Luwians, Minoans, Greeks, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Philistines and Parthians.

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha, modern Tell Ibrahim, is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. The site of Tell Uqair is just to the north. The city was occupied from the Old Akkadian period until the Hellenistic period. The city-god of Kutha was Meslamtaea, related to Nergal, and his temple there was named E-Meslam.

Babylonian religion is the religious practice of Babylonia. Babylonia's mythology was greatly influenced by its Sumerian counterparts and was written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myths were usually either written in Sumerian or Akkadian. Some Babylonian texts were translations into Akkadian from Sumerian of earlier texts, but the names of some deities were changed.

Marduk-apla-iddina I, contemporarily written in cuneiform as 𒀭𒀫𒌓𒌉𒍑𒋧𒈾dAMAR.UTU-IBILA-SUM-na and meaning in Akkadian: "Marduk has given an heir", was the 34th Kassite king of Babylon c. 1171–1159 BC. He was the son and successor of Meli-Shipak II, from whom he had previously received lands, as recorded on a kudurru, and he reigned for 13 years. His reign is contemporary with the Late Bronze Age collapse. He is sometime referred to as Merodach-Baladan I.

Nebuchadnezzar I, reigned c. 1121–1100 BC, was the fourth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and Fourth Dynasty of Babylon. He ruled for 22 years according to the Babylonian King List C, and was the most prominent monarch of this dynasty. He is best known for his victory over Elam and the recovery of the cultic idol of Marduk.

Ninurta-apal-Ekur, inscribed mdMAŠ-A-é-kur, meaning “Ninurta is the heir of the Ekur,” was a king of Assyria in the early 12th century BC who usurped the throne and styled himself king of the universe and priest of the gods Enlil and Ninurta. His reign overlaps the reigns of his Babylonian contemporaries Adad-šuma-uṣur and Meli-Šipak.

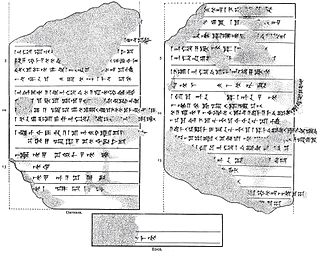

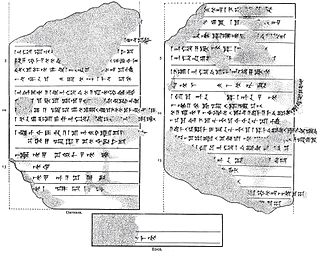

Nazi-Maruttaš, typically inscribed Na-zi-Ma-ru-ut-ta-aš or mNa-zi-Múru-taš, Maruttašprotects him, was a Kassite king of Babylon c. 1307–1282 BC and self-proclaimed šar kiššati, or "King of the World", according to the votive inscription pictured. He was the 23rd of the dynasty, the son and successor of Kurigalzu II, and reigned for twenty six years.

Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē, inscribed mdAMAR.UTU-na-din-MU, reigned c. 1095–1078 BC, was the sixth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon. He is best known for his restoration of the Eganunmaḫ in Ur and the famines and droughts that accompanied his reign.

Adad-šuma-uṣur, inscribed dIM-MU-ŠEŠ, meaning "O Adad, protect the name!," and dated very tentatively c. 1216–1187 BC, was the 32nd king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon and the country contemporarily known as Karduniaš. His name was wholly Babylonian and not uncommon, as for example the later Assyrian King Esarhaddon had a personal exorcist, or ašipu, with the same name who was unlikely to have been related. He is best known for his rude letter to Aššur-nirari III, the most complete part of which is quoted below, and was enthroned following a revolt in the south of Mesopotamia when the north was still occupied by the forces of Assyria, and he may not have assumed authority throughout the country until around the 25th year of his 30-year reign, although the exact sequence of events and chronology remains disputed.

Adad-apla-iddina, typically inscribed in cuneiform mdIM-DUMU.UŠ-SUM-na, mdIM-A-SUM-na or dIM-ap-lam-i-din-[nam] meaning the storm god “Adad has given me an heir”, was the 8th king of the 2nd Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon and ruled c. 1064–1043. He was a contemporary of the Assyrian King Aššur-bêl-kala and his reign was a golden age for scholarship.

Marduk-balāssu-iqbi, inscribed mdAMAR.UTU-TI-su-iq-bi or mdSID-TI-zu-DUG4, meaning "Marduk has promised his life," was the 8th king of the Dynasty of E of Babylon; he was the successor of his father Marduk-zākir-šumi I, and was the 4th and final generation of Nabû-šuma-ukin I's family to reign. He was contemporary with his father's former ally, Šamši-Adad V of Assyria, who may have been his brother-in-law, who was possibly married to his (Marduk's) sister Šammu-ramat, the legendary Semiramis, and who was to become his nemesis.

The office of šandabakku, inscribed 𒇽𒄘𒂗𒈾 (LÚGÚ.EN.NA) or sometimes as 𒂷𒁾𒁀𒀀𒂗𒆤𒆠, the latter designation perhaps meaning "archivist of Enlil," was the name of the position of governor of the Mesopotamian city of Nippur from the Kassite period onward. Enlil, as the tutelary deity of Nippur, had been elevated in prominence and was shown special veneration by the Kassite monarchs, it being the most common theophoric element in their names. This caused the position of the šandabakku to become very prestigious and the holders of the office seem to have wielded influence second only to the king.

Chronicle P, known as Chronicle 22 in Grayson’s Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles and Mesopotamian Chronicle 45: "Chronicle of the Kassite Kings" in Glassner's Mesopotamian Chronicles is named for T. G. Pinches, the first editor of the text. It is a chronicle of the second half of the second millennium BC or the Kassite period, written by a first millennium BC Babylonian scribe.

The estate of Takil-ana-ilīšu kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian white limestone narû, or entitlement stela, dating from the latter part of the Kassite era which gives a history of the litigation concerning a contested inheritance over three generations or more than forty years. It describes a patrimonial redemption, or "lineage claim," and provides a great deal of information concerning inheritance during the late Bronze Age. It is identified by its colophon, asumittu annītu garbarê šalati kanīk dīnim, “this stela is a copy of three sealed documents with (royal) edicts” and records the legal judgments made in three successive reigns of the kings, Adad-šuma-iddina, Adad-šuma-uṣur and Meli-Šipak. It is a contemporary text which confirms the sequence of these Kassite monarchs given on the Babylonian king list and provides the best evidence that the first of these was unlikely to have been merely an Assyrian appointee during their recent hegemony over Babylonia by Tukulti-Ninurta I, as his judgments were honored by the later kings.

The Eclectic Chronicle, referred to in earlier literature as the New Babylonian Chronicle, is an ancient Mesopotamian account of the highlights of Babylonian history during the post-Kassite era prior to the 689 BC fall of the city of Babylon. It is an important source of historiography from the period of the early iron-age dark-age with few extant sources to support its telling of events.

The Land grant to Marduk-zākir-šumi kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian narû, or entitlement stele, recording the gift (irīmšu) of 18 bur 2 eše of corn-land by Kassite king of Babylon Marduk-apla-iddina I to his bēl pīḫati, or a provincial official. The monument is significant in part because it shows the continuation of royal patronage in Babylonia during a period when most of the near East was beset by collapse and confusion, and in part due to the lengthy genealogy of the beneficiary, which links him to his illustrious ancestors.