Armenian is an Indo-European language and the sole member of an independent branch of that language family. It is the native language of the Armenian people and the official language of Armenia. Historically spoken in the Armenian highlands, today Armenian is widely spoken throughout the Armenian diaspora. Armenian is written in its own writing system, the Armenian alphabet, introduced in 405 AD by the canonized saint Mesrop Mashtots. The estimated number of Armenian speakers worldwide is between five and seven million.

The Hurrians were a people who inhabited the Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age. They spoke the Hurrian language, and lived throughout northern Syria, upper Mesopotamia and southeastern Anatolia.

The Northeast Caucasian languages, also called East Caucasian, Nakh-Daghestani or Vainakh-Daghestani, or sometimes Caspian languages, is a family of languages spoken in the Russian republics of Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia and in Northern Azerbaijan as well as in Georgia and diaspora populations in Western Europe and the Middle East. According to Glottolog, there are currently 36 Nakh-Dagestanian languages.

The Alarodian languages are a proposed language family that encompasses the Northeast Caucasian (Nakh–Dagestanian) languages and the extinct Hurro-Urartian languages.

Hurrian is an extinct Hurro-Urartian language spoken by the Hurrians (Khurrites), a people who entered northern Mesopotamia around 2300 BC and had mostly vanished by 1000 BC. Hurrian was the language of the Mitanni kingdom in northern Mesopotamia and was likely spoken at least initially in Hurrian settlements in modern-day Syria.

Urartian or Vannic is an extinct Hurro-Urartian language which was spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu, which was centered on the region around Lake Van and had its capital, Tushpa, near the site of the modern town of Van in the Armenian highlands. Its past prevalence is unknown. While some believe it was probably dominant around Lake Van and in the areas along the upper Zab valley, others believe it was spoken by a relatively small population who comprised a ruling class.

The Kura–Araxes culture was an archaeological culture that existed from about 4000 BC until about 2000 BC, which has traditionally been regarded as the date of its end; in some locations it may have disappeared as early as 2600 or 2700 BC. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; it spread north in the Caucasus by 3000 BC.

Armenian mythology originated in ancient Indo-European traditions, specifically Proto-Armenian, and gradually incorporated Hurro-Urartian, Mesopotamian, Iranian, and Greek beliefs and deities.

The origin of the Armenians is a topic concerned with the emergence of the Armenian people and the country called Armenia. The earliest universally accepted reference to the people and the country dates back to the 6th century BC Behistun Inscription, followed by several Greek fragments and books. The earliest known reference to a geopolitical entity where Armenians originated from is dated to the 13th century BC as Uruatri in Old Assyrian. Historians and Armenologists have speculated about the earlier origin of the Armenian people, but no consensus has been achieved as of yet. Genetic studies show that Armenian people are indigenous to historical Armenia, showing little to no signs of admixture since around the 13th century BC.

Some loanwords in the variant of the Hurrian language spoken in the Mitanni kingdom, during the 2nd millennium BCE, are identifiable as originating in an Indo-Aryan language; these are considered to constitute an Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni. The words in question are theonyms, proper names and technical terminology related to horses (hippological).

Armenia is located in the Caucasus region of south-eastern Europe. Armenian is the official language in Armenia and is spoken as a first language by the majority of its population. Armenian is a pluricentric language with two modern standardized forms: Eastern Armenian and Western Armenian. Armenia's constitution does not specify the linguistic standard. In practice, the Eastern Armenian language dominates government, business, and everyday life in Armenia.

The name Armenia entered English via Latin, from Ancient Greek Ἀρμενία.

Proto-Armenian is the earlier, unattested stage of the Armenian language which has been reconstructed by linguists. As Armenian is the only known language of its branch of the Indo-European languages, the comparative method cannot be used to reconstruct its earlier stages. Instead, a combination of internal and external reconstruction, by reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European and other branches, has allowed linguists to piece together the earlier history of Armenian.

Tzovinar (Ծովինար) or Nar (Նար) was the Armenian goddess of water, sea, and rain. She was a fierce goddess, who forced the rain to fall from the heavens with her fury.

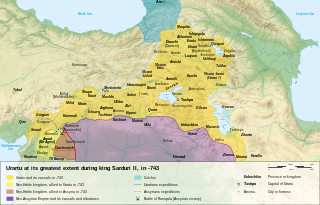

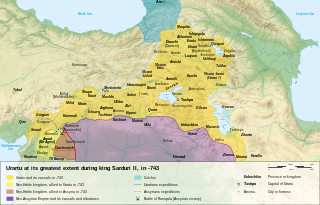

Urartu was an Iron Age kingdom centered around Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands. It extended from the eastern bank of the upper Euphrates River to the western shores of Lake Urmia and from the mountains of northern Iraq to the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. The kingdom emerged in the mid-9th century BC and dominated the Armenian Highlands in the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Urartu frequently warred with Assyria and became, for a time, the most powerful state in the Near East. Weakened by constant conflict, it was eventually conquered by the Iranian Medes in the early 6th century BC. Archaeologically, it is noted for its large fortresses and sophisticated metalwork. Its kings left behind cuneiform inscriptions in the Urartian language, a member of the Hurro-Urartian language family. Since its re-discovery in the 19th century, Urartu, which is commonly believed to have been at least partially Armenian-speaking, has played a significant role in Armenian nationalism.

The Armeno-Phrygians are a hypothetical people of West Asia during the Bronze Age, the Bronze Age collapse, and its aftermath. They would be the common ancestors of both Phrygians and Proto-Armenians. In turn, Armeno-Phrygians would be the descendants of the Graeco-Phrygians, common ancestors of Greeks, Phrygians, and also of Armenians.

The name Armeno-Phrygian is used for a hypothetical language branch, which would include the languages spoken by the Phrygians and the Armenians, and would be a branch of the Indo-European language family, or a sub-branch of either the proposed "Graeco-Armeno-Aryan" or "Armeno-Aryan" branches. According to this hypothesis, Proto-Armenian was a language descendant from a common ancestor with Phrygian and was closely related to it. Proto-Armenian differentiated from Phrygian by language evolution over time but also by the Hurro-Urartian language substrate influence. Classification is difficult because little is known of Phrygian, but Proto-Armenian arguably forms a subgroup with Greek and Indo-Iranian.

Etiuni was the name of an early Iron Age tribal confederation in northern parts of Araxes rivers, roughly corresponding to the subsequent Ayrarat Province of the Kingdom of Armenia. Etiuni was frequently mentioned in the records of Urartian kings, who led numerous campaigns into Etiuni territory. It is very likely it was the "Etuna" or "Etina" which contributed to the fall of Urartu, according to Assyrian texts. Some scholars believe it had an Armenian-speaking population.