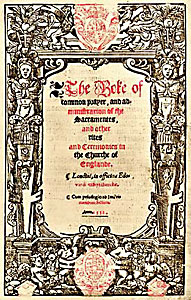

The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The first prayer book, published in 1549 in the reign of King Edward VI of England, was a product of the English Reformation following the break with Rome. The work of 1549 was the first prayer book to include the complete forms of service for daily and Sunday worship in English. It contained Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, the Litany, and Holy Communion and also the occasional services in full: the orders for Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, "prayers to be said with the sick", and a funeral service. It also set out in full the "propers" : the introits, collects, and epistle and gospel readings for the Sunday service of Holy Communion. Old Testament and New Testament readings for daily prayer were specified in tabular format as were the Psalms and canticles, mostly biblical, that were provided to be said or sung between the readings.

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Reformation. It permanently shaped the Church of England's doctrine and liturgy, laying the foundation for the unique identity of Anglicanism.

The Directory for Public Worship is a liturgical manual produced by the Westminster Assembly in 1644 to replace the Book of Common Prayer. Approved by the Parliament of England in 1644 and the Parliament of Scotland in 1645, the Directory is part of the Westminster Standards, together with the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Westminster Shorter Catechism, the Westminster Larger Catechism, and the Form of Church Government.

James VI and I, King of Scots, King of England, and King of Ireland, faced many complicated religious challenges during his reigns in Scotland and England.

Laudianism was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England, promulgated by Archbishop William Laud and his supporters. It rejected the predestination upheld by the previously dominant Calvinism in favour of free will, and hence the possibility of salvation for all men. Laudianism had a significant impact on the Anglican high church movement and its emphasis on liturgical ceremony and clerical hierarchy. Laudianism was the culmination of the move towards Arminianism in the Church of England, but was neither purely theological in nature, nor restricted to the English church.

The 1928 Book of Common Prayer, sometimes known as the Deposited Book, is a liturgical book which was proposed as a revised version of the Church of England's 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Opposing what they saw as an Anglo-Catholic revision that would align the Church of England with the Catholic Church—particularly through expanding the practice of the reserved sacrament—Protestant evangelicals and nonconformists in Parliament put up significant resistance, driving what became known as the Prayer Book Crisis.

The reign of Elizabeth I of England, from 1558 to 1603, saw the start of the Puritan movement in England, its clash with the authorities of the Church of England, and its temporarily effective suppression as a political movement in the 1590s by judicial means. This led to the further alienation of Anglicans and Puritans from one another in the 17th century during the reigns of King James and King Charles I, that eventually brought about the English Civil War, the brief rule of the Puritan Lord Protector of England Oliver Cromwell, the English Commonwealth, and as a result the political, religious, and civil liberty that is celebrated today in all English speaking countries.

Primer is the name for a variety of devotional prayer books that originated among educated medieval laity in the 14th century, particularly in England. While the contents of primers have varied dependent on edition, they often contained portions of the Psalms and Latin liturgical practices such as the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Medieval primers were often similar to and sometimes considered synonymous with the also popular book of hours ; typically, a medieval horae was referred to as a primer in Middle English.

The 1979 Book of Common Prayer is the official primary liturgical book of the U.S.-based Episcopal Church. An edition in the same tradition as other versions of the Book of Common Prayer used by the churches within the Anglican Communion and Anglicanism generally, it contains both the forms of the Eucharistic liturgy and the Daily Office, as well as additional public liturgies and personal devotions. It is the fourth major revision of the Book of Common Prayer adopted by the Episcopal Church, and succeeded the 1928 edition. The 1979 Book of Common Prayer has been translated into multiple languages and is considered a representative production of the 20th-century Liturgical Movement.

The 1929 Scottish Prayer Book is an official liturgical book of the Scotland-based Scottish Episcopal Church. The 1929 edition follows from the same tradition of other versions of the Book of Common Prayer used by the churches within the Anglican Communion and Anglicanism generally, with the unique liturgical tradition of Scottish Anglicanism. It contains both the forms of the Eucharistic liturgy and Daily Office, as well as additional public liturgies and personal devotions. The second major revision of the Book of Common Prayer following the full independence of the Scottish Episcopal Church, the 1929 Scottish Prayer Book succeeded the 1912 edition and was intended to serve alongside the Church of England's 1662 prayer book.

The 1552 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI, was the second version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) and contained the official liturgy of the Church of England from November 1552 until July 1553. The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services. The 1552 prayer book was revised to be explicitly Reformed in its theology.

The 1962 Book of Common Prayer is an authorized liturgical book of the Canada-based Anglican Church of Canada. The 1962 prayer book is often also considered the 1959 prayer book, in reference to the year the revision was first approved for an "indefinite period" of use beginning in 1960. The 1962 edition follows from the same tradition of other versions of the Book of Common Prayer used by the churches within the Anglican Communion and Anglicanism generally. It contains both the Eucharistic liturgy and Daily Office, as well as additional public liturgies and personal devotions. The second major revision of the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Church of Canada, the 1962 Book of Common Prayer succeeded the 1918 edition, which itself had replaced the Church of England's 1662 prayer book. While supplanted by the 1985 Book of Alternative Services as the Anglican Church of Canada's primary Sunday service book, the 1962 prayer book continues to see usage.

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer is an authorised liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican bodies around the world. In continuous print and regular use for over 360 years, the 1662 prayer book is the basis for numerous other editions of the Book of Common Prayer and other liturgical texts. Noted for both its devotional and literary quality, the 1662 prayer book has influenced the English language, with its use alongside the King James Version of the Bible contributing to an increase in literacy from the 16th to the 20th century.

An ordinal, in a modern context, is a liturgical book that contains the rites and prayers for the ordination and consecration to the Holy Orders of deacons, priests, and bishops in multiple Christian denominations, especially the Edwardine Ordinals within Anglicanism. The term "ordinal" has been applied to the prayers and ceremonies for ordinations in the Catholic Church, where the pontificals of the Latin liturgical rites typically compile them along with other liturgies exclusive to bishops. In medieval liturgies, ordinals supplied instruction on how to use the various books necessary to celebrate a liturgy and added rubrical direction.

The Edwardine Ordinals are two ordinals primarily written by Thomas Cranmer as influenced by Martin Bucer and first published under Edward VI, the first in 1550 and the second in 1552, for the Church of England. Both liturgical books were intended to replace the ordination liturgies contained within medieval pontificals in use before the English Reformation.

Since the 18th century, there have been several editions of the Book of Common Prayer produced and revised for use by Unitarians. Several versions descend from an unpublished manuscript of alterations to the Church of England's 1662 Book of Common Prayer originally produced by English philosopher and clergyman Samuel Clarke in 1724, with descendant liturgical books remaining in use today.

The 1559 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Elizabethan prayer book, is the third edition of the Book of Common Prayer and the text that served as an official liturgical book of the Church of England throughout the Elizabethan era.

The 1637 Book of Common Prayer, commonly known as the Scottish Prayer Book or Scottish liturgy, was a version of the English Book of Common Prayer revised for use by the Church of Scotland. The 1637 prayer book shared much with the 1549 English prayer book—rather than the later, more reformed English revisions—and contained Laudian liturgical preferences with some concessions to a Scottish and Presbyterian audience. Charles I, as King of Scotland and England had wished to impose the liturgical book to align Scottish worship with that of the Church of England. However, after a coordinated series of protests—including the legendary opposition by Jenny Geddes at St Giles' Cathedral—the 1637 prayer book was rejected.

A sentence, particularly in Anglican services, is a short passage from the Bible that is recited in Christian liturgies. For example, with the Church of England's currently authorized 1662 Book of Common Prayer, sentences are used at several points within different rites: prescribed sentences are to be recited before Morning and Evening Prayers, at least one sentence may be said or sung during the Holy Communion office offertory, and sentences appear at multiple points during the burial service.

Free and Candid Disquisitions is a 1749 pamphlet written and compiled by John Jones, a Welsh Church of England clergyman, and published anonymously. The text advocated for reforming the Church of England to enable the reintegration of independent English Protestants, particularly through changes to the liturgies of the mandated 1662 prayer book.