Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite. Washington was from the last generation of Black American leaders born into slavery and became the leading voice of the former slaves and their descendants. They were newly oppressed in the South by disenfranchisement and the Jim Crow discriminatory laws enacted in the post-Reconstruction Southern states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Interstate 65 (I-65) is a major north–south Interstate Highway in the central United States. As with most primary Interstates ending in 5, it is a major crosscountry, north–south route, connecting between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. Its southern terminus is located at an interchange with I-10 in Mobile, Alabama, and its northern terminus is at an interchange with US 12 (US 12), and US 20 in Gary, Indiana, just southeast of Chicago. I-65 connects several major metropolitan areas in the Midwest and Southern US. It connects the four largest cities in Alabama: Mobile, Montgomery, Birmingham, and Huntsville. It also serves as one of the main north–south routes through Nashville, Tennessee; Louisville, Kentucky; and Indianapolis, Indiana, each a major metropolitan area in its respective state.

Decatur is the largest city and county seat of Morgan County in the U.S. state of Alabama. Nicknamed "The River City", it is located in northern Alabama on the banks of Wheeler Lake, along the Tennessee River. The population in 2020 was 57,938.

Tuskegee University, formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The Scottsboro Boys were nine African American male teenagers accused in Alabama of raping two white women in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The cases included a lynch mob before the suspects had been indicted, all-white juries, rushed trials, and disruptive mobs. It is commonly cited as an example of a legal injustice in the United States legal system.

The Springfield race riot of 1908 consisted of events of mass racial violence committed against African Americans by a mob of about 5,000 white Americans and European immigrants in Springfield, Illinois, between August 14 and 16, 1908. Two black men had been arrested as suspects in a rape, and attempted rape and murder. The alleged victims were two young white women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred them out of the city, the whites furiously spread out to attack black neighborhoods, murdered black citizens on the streets, and destroyed black businesses and homes. The state militia was called out to quell the rioting.

Austin High School is located in Decatur, Alabama, United States. It is part of the Decatur City Schools system and enrolls over 1,400 students. Since its establishment in 1962, Austin has been one of two high schools in the Decatur area. It boasts a variety of programs.

Horace Mann Bond was an American historian, college administrator, social science researcher and the father of civil-rights leader Julian Bond. He earned graduate and doctoral degrees from University of Chicago at a time when only a small percentage of any young adults attended any college. He was an influential leader at several historically black colleges and was appointed the first president of Fort Valley State University in Georgia in 1939, where he managed its growth in programs and revenue. In 1945, he became the first African-American president of Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

Joseph Edwin Washington was an American politician and a member of the United States House of Representatives for the 6th congressional district of Tennessee.

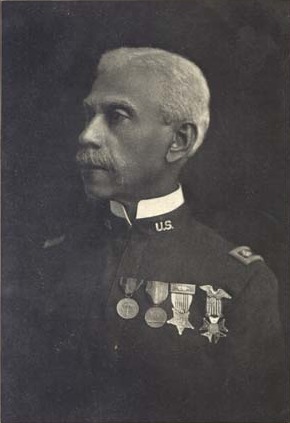

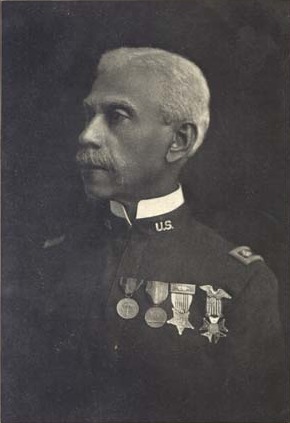

Allen Allensworth was an American chaplain, colonel, city founder, and theologian. Born into slavery in Kentucky, he escaped during the American Civil War by joining the 44th Illinois Volunteers as a Union soldier. After being ordained as a Baptist minister by the Fifth Street Baptist Church, April 9, 1871, he worked as a teacher, led several churches, and was appointed as a chaplain in the United States Army. In 1886, he gained appointment as a military chaplain to a unit of Buffalo Soldiers in the West, becoming the first African American to reach the rank of lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. He served in the Army for 20 years, retiring in 1906.

The 51st Indiana Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

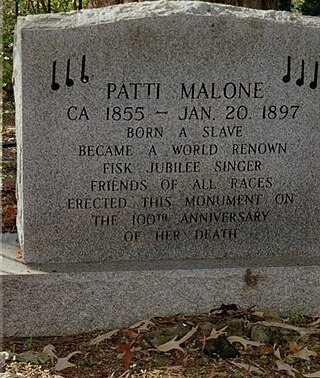

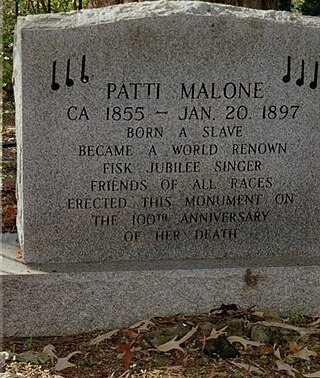

Patti J. Malone, was best known as a mezzo-soprano vocalist.

Esther Victoria Cooper Jackson was an American civil rights activist, social worker, and communist activist. She worked with Shirley Graham Du Bois, W. E. B. Du Bois, Edward Strong, and Louis E. Burnham, and was one of the founding editors of the magazine Freedomways, a theoretical, political and literary journal published from 1961 to 1985. She also served as organizational and executive secretary at the Southern Negro Youth Congress.

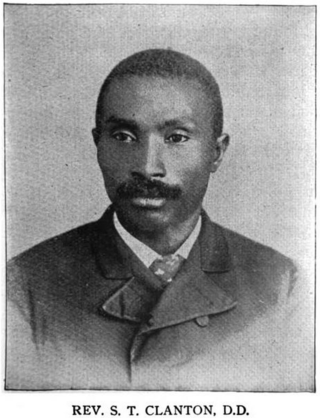

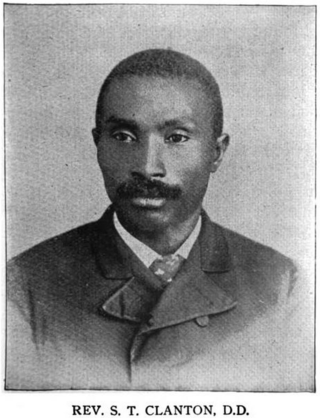

Solomon T. Clanton was a leader in the Baptist Church. He was educated in New Orleans and Chicago and became the first black graduate of the theological department at the Baptist Union Theological Seminary at Morgan Park, Chicago, Illinois, associated with the University of Chicago. He spent his career as an educator and leader in the Baptist Church. He served as a professor at Leland University, Alabama A&M University, and Selma University, and before his death as assistant librarian at the University of Chicago. He was acting president for a short time at Alabama A&M and was dean of the theological department at Selma University. During his career, he was also an educator in high schools and Sunday schools.

William R. Pettiford was a minister and banker in Birmingham, Alabama. Early in his career he worked as a minister and teacher in various towns in Alabama, moving to the 16th Street Baptist Church in 1883 and serving there for about ten years. In 1890 he founded the Alabama Penny Savings Bank. It played an important role in black economic development in Alabama and in the South during the 25 years it existed. Pettiford has been called the most significant institutional builder and leader in the African American community in Birmingham during the period in which he lived. In 1897 he was said to be next to Booker T. Washington the black man who has done the most in the South for blacks.

Cornelia Bowen (1865-1934) was an African American teacher and school founder from Alabama. She was in the first graduating class of the Tuskegee Institute and went on to found the Mount Meigs Colored Institute as well as the Mt. Meigs Negro Boys' Reformatory. Based on the principles of the Tuskegee Institute, where she was trained, Bowen created industrial schools to teach students to thrive from their own industry. She was a member of both the state and national Colored Women's Federated Clubs and served as an officer of both organizations. She also was elected as the first woman president of the Alabama Negro Teacher's Association.

Lady Mary Alice Seymour was a 19th-century American musician, author, elocutionist, and critic. She was referred to as "Octavia Hensel" in the music world, where she was an internationally known music critic. As a critic, Seymour was renowned. Her musical nature, her superior education, her thorough knowledge of the laws of theory and familiarity with the works of the great composers of the classic, romantic and Wagnerian schools, and the later schools of harmony, gave her a point of vantage above the ordinary. She was one of the original staff writers on the Musical Courier, having been its correspondent from Vienna and other European centers. Seymour played the piano, harp, guitar and organ, but never appeared on the stage, except for charitable events, as her relatives were opposed to her pursuing a professional life. A "confirmed bluestocking", Seymour was also a polyglot who spoke seven languages fluently: German, French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Hungarian dialects. She died in 1897.

George Taylor was an African-American man who was lynched on November 5, 1918, after he was accused of raping a white woman named Ruby Rogers in her home near Rolesville, North Carolina, United States, about 20 mi (32 km) northeast of Raleigh. Described in the press as a "genuine old-fashioned lynching", it is the only known lynching in Wake County, North Carolina. The lynching was commemorated on its anniversary in 2018.

A training school, or county training school, was a type of segregated school for African American students found in the United States and Canada. In the Southern United States they were established to educate African Americans at elementary and secondary levels, especially as teachers; and in the Northern United States they existed as educational reformatory schools. A few training schools still exist, however they exist in a different context.