Female genital mutilation (FGM) is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the vulva. The practice is found in some countries of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and within their respective diasporas. As of 2023, UNICEF estimates that "at least 200 million girls... in 31 countries"—including Indonesia, Iraq, Yemen, and 27 African countries including Egypt—had been subjected to one or more types of FGM.

Religious circumcision is generally performed shortly after birth, during childhood, or around puberty as part of a rite of passage. Circumcision for religious reasons is most frequently practiced by members of the Jewish and Islamic faiths.

Circumcision likely has ancient roots among several ethnic groups in sub-equatorial Africa, Egypt, and Arabia, though the specific form and extent of circumcision has varied. Ritual male circumcision is known to have been practiced by South Sea Islanders, Aboriginal peoples of Australia, Sumatrans, Incas, Aztecs, Mayans and Ancient Egyptians. Today it is still practiced by Jews, Muslims, Coptic Christians, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Druze, Samaritans and some tribes in East and Southern Africa, as well as in the United States, South Korea and Philippines.

The Bukusu people are one of the 17 Kenyan tribes of the Luhya Bantu people of East Africa residing mainly in the counties of Bungoma and Trans Nzoia. They are the largest tribe of the Luhya nation, with 1,188,963 identifying as Bukusu in the 2019 Kenyan census. They speak the Bukusu dialect.

Male circumcision reduces the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission from HIV positive women to men in high risk populations.

The Gisu people, or Bamasaba people of Elgon, are a Bantu tribe and Bantu-speaking ethnic group of the Masaba people in eastern Uganda, closely related to the Bukusu people of Kenya. Bamasaba live mainly in the Mbale District of Uganda on the slopes of Mount Elgon. The Bagisu are estimated to be about 1,646,904 people making up 4.9% of the total population according to the 2014 National Census of Uganda.

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topical or locally injected anesthesia is generally used to reduce pain and physiologic stress. Circumcision is generally electively performed, most commonly done as a form of preventive healthcare, as a religious obligation, or as a cultural practice. It is also an option for cases of phimosis, other pathologies that do not resolve with other treatments, and chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs). The procedure is contraindicated in cases of certain genital structure abnormalities or poor general health.

The prevalence of circumcision is the percentage of males in a given population who have been circumcised, with the procedure most commonly being performed as a part of preventive healthcare, a religious obligation, or cultural practice.

The very high rate of human immunodeficiency virus infection experienced in Uganda during the 1980s and early 1990s created an urgent need for people to know their HIV status. The only option available to them was offered by the National Blood Transfusion Service, which carries out routine HIV tests on all the blood that is donated for transfusion purposes. The great need for testing and counseling resulted in a group of local non-governmental organizations such as The AIDS Support Organisation, Uganda Red Cross, Nsambya Home Care, the National Blood Bank, the Uganda Virus Research Institute together with the Ministry of Health establishing the AIDS Information Centre in 1990. This organization worked to provide HIV testing and counseling services with the knowledge and consent of the client involved.

The controversy on religious male circumcision in early Christianity has played an important role in the history of Christianity and Christian theology.

The Maragoli, or Logoli (Ava-Logooli), are now the second-largest ethnic group of the 6 million-strong Luhya nation in Kenya, numbering around 2.1 million, or 15% of the Luhya people according to the last Kenyan census. Their language is called Logoli, Lulogooli, Ululogooli, or Maragoli. The name Maragoli probably emerged later on after interaction of the people with missionaries of the Quaker Church.

There is a widespread view among practitioners of female genital mutilation (FGM) that it is a religious requirement, although prevalence rates often vary according to geography and ethnic group. There is an ongoing debate about the extent to which the practice's continuation is influenced by custom, social pressure, lack of health-care information, and the position of women in society. The procedures confer no health benefits and can lead to serious health problems.

The Tachoni is one of the tribes that occupy the western part of Kenya,its known for its gallant defense of the Chetambe in 1895 when resisting British rule. Tachoni people were masters at building forts such as Chetambe, Lumboka, and Kiliboti. It was their defiance of colonialism that led to the colonial government putting the entire region occupied by the Tachoni under administration of paramount chiefs drawn from Bunyala and Wanga communities. Sharing land with the Abanyala, the Kabras, Nandi, and Bukusu tribe. They live mainly in Webuye, Chetambe Hills, Ndivisi Matete sub-county-Lwandeti, Maturu, Mayoyo, Lukhokho, Kiliboti, Kivaywa, Chepsai, and Lugari sub-county in Kakamega County. Most Tachoni clans living in Bungoma speak the ' Olutachoni dialect which is a hybrid of the luhyia language of the luhyia people. Since they lost their original dialect during the divide and rule system used by the whites to scatter them for being resistants to their colonialism, they had to find a way to interact with their new neighbors and thats why they're subsequently mistaken as Bukusus. They spread from Kakamega county to Trans-Nzoia County, webuye especially around Kitale, Tambach in Iten Nandi in areas like kabiyet and kapsisiwa, kericho and to Uasin Gishu County near Turbo, Eldoret.

Among the Tachoni clans are Abachikha -further divided into Abakobolo, Abamuongo, Abachambai,Abamakhanga, Abacharia, and Abakabini, Abamarakalu, Abangachi -who are further divided into: Abawaila, Abakhumaya and Abawele, Abasang'alo, Abasamo, Abayumbu, Abaluu, Abarefu,Abanyangali, Abamuchembi, Abamakhuli, Abasioya, Abaabichu,Abacheo, Abamachina,Abaengele, Abamutama, Abakafusi, Abasonge, Abasaniaka, Abaabiya also known as Abakatumi, Abakubwayi,Abakamutebi, Abakamukong, Abamweya, Abalukulu,Abawande, Abatukiika, Abachimuluku. Note that the morpheme 'aba' means 'people'.

Forced circumcision is the circumcision of men and boys against their will. In a biblical context, the term is used especially in relation to Paul the Apostle and his polemics against the circumcision controversy in early Christianity. Forced circumcisions have occurred in a wide range of situations, most notably in the compulsory conversion of non-Muslims to Islam and the forced circumcision of Teso, Turkana and Luo men in Kenya, as well as the abduction of South African teenage boys to so-called circumcision schools. In South Africa, custom allows uncircumcised Xhosa-speaking men past the age of circumcision to be overpowered by other men and forcibly circumcised. Routine infant circumcision, as performed in some highly developed nations such as the United States and South Korea, may also be classified as forced circumcision, even if performed in a clinical setting. Any circumcision performed on an infant could be considered forced circumcision due to the inability of the infant to give consent.

Tulì is a Filipino rite of male circumcision. It has a long historical tradition and is considered an obligatory rite of passage for males; those who have not undergone the ritual are ridiculed and labeled supót by their peers.

The Ndut is a rite of passage as well as a religious education commanded by Serer religion that every Serer must go through once in their lifetime. The Serer people being an ethnoreligious group, the Ndut initiation rite is also linked to Serer culture. From the moment a Serer child is born, education plays a pivotal role throughout their life cycle. The ndut is one of these phases of their life cycle. In Serer society, education lasts a lifetime, from infancy to old age.

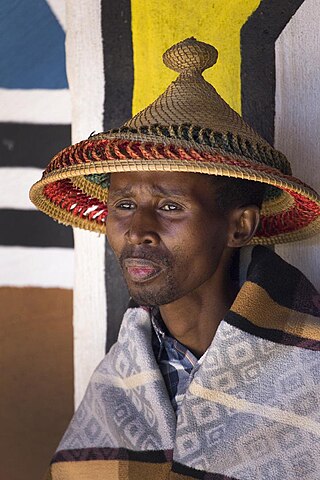

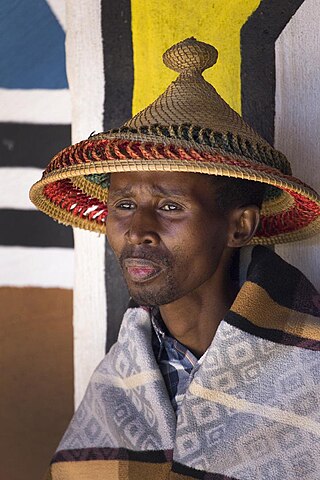

Ulwaluko, traditional circumcision and initiation from childhood to adulthood, is an ancient initiation rite practised by the Xhosa people, and is commonly practised throughout South Africa. The ritual is traditionally intended as a teaching institution, to prepare young males for the responsibilities of manhood. Therefore, initiates are called abakhwetha in isiXhosa: aba means a group, and kwetha means to learn. A single male in the group is known as an umkhwetha. A male who has not undergone initiation is referred to as inkwenkwe (boy), regardless of his age, and is not allowed to take part in male activities such as tribal meetings.

Lebollo la banna is a Sesotho term for male initiation.

A sexual rite of passage is a ceremonial event that marks the passage of a young person to sexual maturity and adulthood, or a widow from the married state to widowhood, and involves some form of sexual activity.

Circumcision has played a significant cultural, social, and religious role in various global cultures over the course of world history. This has subsequently led to widely varying views related to the practice.