Related Research Articles

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a Ruthenian nobleman and military commander of Ukrainian Cossacks as Hetman of the Zaporozhian Host, which was then under the suzerainty of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the creation of an independent Cossack state in Ukraine. In 1654, he concluded the Treaty of Pereiaslav with the Russian Tsar and allied the Cossack Hetmanate with Tsardom of Russia, thus placing central Ukraine under Russian protection. During the uprising the Cossacks led a massacre of thousands of Jewish people during 1648–1649 as one of the most traumatic events in the history of the Jews in Ukraine and Ukrainian nationalism.

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor. Today Belarusians, Russians and Ukrainians are the existent East Slavic nations. Rusyns can also be considered as a separate nation, although they are often considered a subgroup of the Ukrainian people.

Donetsk Oblast, also referred to as Donechchyna, is an oblast in eastern Ukraine. It is Ukraine's most populous province, with around 4.1 million residents. Its administrative centre is Donetsk, though due to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, the regional administration was moved to Kramatorsk. Historically, the region has been an important part of the Donbas region. From its creation in 1938 until November 1961, it bore the name Stalino Oblast, in honour of Joseph Stalin. As part of the de-Stalinization process, it was renamed after the Siversky Donets river, the main artery of Eastern Ukraine. Its population is estimated at 4,100,280.

Luhansk Oblast, also referred to as Luhanshchyna (Луга́нщина), is the easternmost oblast (province) of Ukraine. Its administrative center is the city of Luhansk. The oblast was established in 1938 and bore the name Voroshilovgrad Oblast until 1958 and again from 1970 to 1991. It has a population of 2,102,921.

The Pereiaslav Agreement or Pereyaslav Agreement was an official meeting that convened for a ceremonial pledge of allegiance by Cossacks to the Tsar of Russia in the town of Pereiaslav, in central Ukraine, in January 1654. The ceremony took place concurrently with ongoing negotiations that started on the initiative of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky to address the issue of the Cossack Hetmanate with the ongoing Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and which concluded the Treaty of Pereiaslav. The treaty itself was finalized in Moscow in April 1654.

The Donbas or Donbass is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. Parts of the Donbas are occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Right-bank Ukraine is a historical and territorial name for a part of modern Ukraine on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding to the modern-day oblasts of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad, as well as the western parts of Kyiv and Cherkasy. It was separated from the left bank during the Ruin.

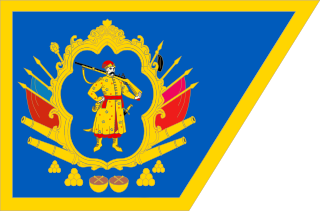

The Cossack Hetmanate, officially the Zaporozhian Host or Army of Zaporozhia, is a historical term for the 17th-18th centuries Ukrainian Cossack state located in central Ukraine. It existed between 1649 and 1764, although its administrative-judicial system persisted until 1782.

The Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth was a proposed European state in the 17th century that would have replaced the existing Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but it was never actually formed.

The Ruin is a historical term introduced by the Cossack chronicle writer Samiilo Velychko (1670–1728) for the political situation in Ukrainian history during the second half of the 17th century.

Russian is the most common first language in the Donbas and Crimea regions of Ukraine and the city of Kharkiv, and the predominant language in large cities in the eastern and southern portions of the country. The usage and status of the language is the subject of political disputes. Ukrainian is the country's only state language since the adoption of the 1996 Constitution, which prohibits an official bilingual system at state level but also guarantees the free development, use and protection of Russian and other languages of national minorities. In 2017 a new Law on Education was passed which restricted the use of Russian as a language of instruction. Nevertheless, Russian remains a widely used language in Ukraine in pop culture and in informal and business communication.

Russians are the largest ethnic minority in Ukraine. This community forms the largest single Russian community outside of Russia in the world. In the 2001 Ukrainian census, 8,334,100 identified as ethnic Russians ; this is the combined figure for persons originating from outside of Ukraine and the Ukrainian-born population declaring Russian ethnicity.

The Wild Fields is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th to 18th centuries to refer to the Pontic steppe in the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. It was the traditional name for the Black Sea steppes in the 16th and 17th centuries. In a narrow sense, it is the historical name for the demarcated and sparsely populated Black Sea steppes between the middle and lower reaches of the Dniester in the west, the lower reaches of the Don and the Siverskyi Donets in the east, from the left tributary of the Dnipro — Samara, and the upper reaches of the Southern Bug — Syniukha and Ingul in the north, to the Black and Azov Seas and Crimea in the south.

The Ukrainians in Kuban in southern Russia constitute a national minority. The region as a whole shares many linguistic, cultural and historic ties with Ukraine.

The Polish minority in Ukraine officially numbers about 144,130, of whom 21,094 (14.6%) speak Polish as their first language. The history of Polish settlement in current territory of Ukraine dates back to 1030–31. In Late Middle Ages, following the extinction of the Rurik dynasty in 1323, the Kingdom of Poland extended east in 1340 to include the lands of Przemyśl and in 1366, Kamianets-Podilskyi. The settlement of Poles became common there after the Polish–Lithuanian peace treaty signed in 1366 between Casimir III the Great of Poland, and Liubartas of Lithuania.

Sweden–Ukraine relations are foreign relations between Sweden and Ukraine. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were established on 13 January 1992. Sweden has an embassy in Kyiv and an honorary consulate in Kakhovka. Ukraine has an embassy in Stockholm. Sweden is a member of the European Union, which Ukraine applied for in 2022. Both countries are members of the OSCE, Council of Europe, World Trade Organization and United Nations.

The Ruthenian nobility originated in the territories of Kievan Rus' and Galicia–Volhynia, which were incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and later the Russian and Austrian Empires. The Ruthenian nobility became increasingly polonized and later russified, while retaining a separate cultural identity.

Southern Ukraine refers, generally, to the territories in the South of Ukraine.

The Luhansk People's Republic or Lugansk People's Republic is an internationally unrecognised republic of Russia in the occupied parts of eastern Ukraine's Luhansk Oblast, with its capital in Luhansk. The LPR was proclaimed by Russian-backed paramilitaries in 2014, and it initially operated as a breakaway state until it was annexed by Russia in 2022.

A variety of social, economical, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic factors contributed to the sparking of unrest in eastern and southern Ukraine in 2014, and the subsequent eruption of the Russo-Ukrainian War, in the aftermath of the early 2014 Revolution of Dignity. Following Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, resurfacing historical and cultural divisions and a weak state structure hampered the development of a unified Ukrainian national identity.

References

- ↑ F.D. Klimchuk, About ethnolinguistic history of Left Bank of Dnieper (in connection to the ethnogenesis of Goriuns). Published in "Goriuns: history, language, culture" Proceedings of International scientific conference, (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, February 13, 2004)

- 1 2 Росіяни [Russians] (in Ukrainian). Congress of National Communities of Ukraine. 2004. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007.

- 1 2 Display Page

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History . University of Toronto Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8020-8390-6 . Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ Дністрянський М.С. Етнополітична географія України. Лівів Літопис, видавництво ЛНУ імені Івана Франка, 2006, page 342 ISBN 966-7007-60-X

- ↑ Miller, Alexei (203). The Ukrainian Question. The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9241-60-1.

- ↑ Magoscy, R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ http://thekievtimes.ua/society/372400-donbass-zabytyj-referendum-1994.html [ dead link ]