Bruhathkayosaurus is a controversial genus of sauropod dinosaur found in the Kallamedu Formation of India. The fragmentary remains were originally described as a theropod, but it was later determined to be a titanosaurian sauropod. Length estimates by researchers exceed those of the titanosaur Argentinosaurus, as longer than 35 metres (115 ft) and weighing over 80 tonnes. A 2023 estimate placed Bruhathkayosaurus as potentially weighing approximately 110–170 tonnes. If the upper estimates of the 2023 records are accurate, Bruhathkayosaurus may have rivalled the blue whale as one of the largest animals to ever exist. However, all of the estimates are based on the dimensions of the fossils described in Yadagiri and Ayyasami (1987), and in 2017, it was reported that the holotype fossils had disintegrated and no longer exist.

Titanosaurus is a dubious genus of sauropod dinosaurs, first described by Richard Lydekker in 1877. It is known from the Maastrichtian Lameta Formation of India.

Antarctosaurus is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now South America. The type species, Antarctosaurus wichmannianus, and a second species, Antarctosaurus giganteus, were described by prolific German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene in 1929. Three additional species of Antarctosaurus have been named since then but later studies have considered them dubious or unlikely to pertain to the genus.

Agustinia is a genus of sauropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of South America. The genus contains a single species, Agustinia ligabuei, known from a single specimen that was recovered from the Lohan Cura Formation of Neuquén Province in Argentina. It lived about 116–108 million years ago, in the Aptian–Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous Period.

Ampelosaurus is a titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now France. Its type species is A. atacis, named by Le Loeuff in 1995. Its remains were found in a level dating from 71.5 million years ago representing the early Maastrichtian.

Huabeisaurus was a genus of dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous. It was a sauropod which lived in what is present-day northern China. The type species, Huabeisaurus allocotus, was first described by Pang Qiqing and Cheng Zhengwu in 2000. Huabeisaurus is known from numerous remains found in the 1990s, which include teeth, partial limbs and vertebrae. Due to its relative completeness, Huabeisaurus represents a significant taxon for understanding sauropod evolution in Asia. Huabeisaurus comes from Kangdailiang and Houyu, Zhaojiagou Town, Tianzhen County, Shanxi province, China. The holotype was found in the unnamed upper member of the Huiquanpu Formation, which is Late Cretaceous (?Cenomanian–?Campanian) in age based on ostracods, charophytes, and fission-track dating.

Epachthosaurus was a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous. It was a basal lithostrotian titanosaur. Its fossils have been found in Central and Northern Patagonia in South America.

Lirainosaurus is a genus of titanosaur sauropod which lived in what is now Spain. The type species, Lirainosaurus astibiae, was described by Sanz, Powell, Le Loeuff, Martinez, and Pereda-Suberbiola in 1999. It was a relatively small sauropod, measuring 4 metres (13 ft) long, possibly up to 6 metres (20 ft) long for the largest individuals, and weighed about 2–4 metric tons.

Phuwiangosaurus is a genus of titanosaur dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian-Hauterivian) Sao Khua Formation of Thailand. The type species, P. sirindhornae, was described by Martin, Buffetaut, and Suteethorn in a 1993 press release and was formally named in 1994. The species was named to honor Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn of Thailand, who was interested in the geology and palaeontology of Thailand, while the genus was named after the Phu Wiang area, where the fossil was discovered.

Gargantuavis is an extinct genus of large, primitive bird containing the single species Gargantuavis philoinos. It is the only member of the monotypic family Gargantuaviidae. Its fossils were discovered in several formations dating to 73.5 and 71.5 million years ago in what is now northern Spain, southern France, and Romania. Gargantuavis is the largest known bird of the Mesozoic, a size ranging between the cassowary and the ostrich, and a mass of 141 kg (311 lb) like modern ostriches, exemplifying the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs was not a necessary condition for the emergence of giant terrestrial birds. It was once thought to be closely related to modern birds, but the 2019 discovery of a pelvis from what was Hateg Island shows several primitive features.

Diamantinasaurus is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod from Australia that lived during the early Late Cretaceous, about 94 million years ago. The type species of the genus is D. matildae, first described and named in 2009 by Scott Hocknull and colleagues based on fossil finds in the Winton Formation. Meaning "Diamantina lizard", the name is derived from the location of the nearby Diamantina River and the Greek word sauros, "lizard". The specific epithet is from the Australian song Waltzing Matilda, also the locality of the holotype and paratype. The known skeleton includes most of the forelimb, shoulder girdle, pelvis, hindlimb and ribs of the holotype, and one shoulder bone, a radius and some vertebrae of the paratype.

Atacamatitan is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Tolar Formation of Chile.

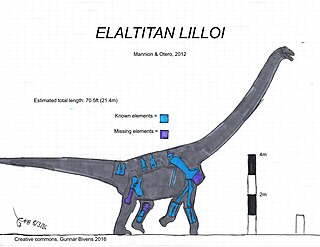

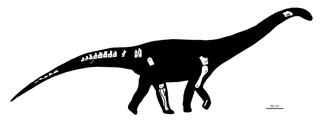

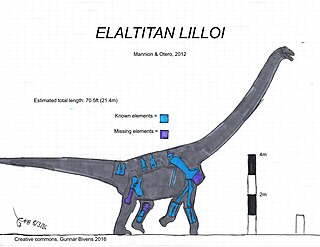

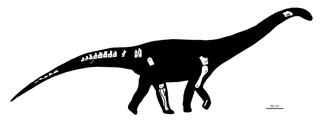

Elaltitan is an extinct genus of large lithostrotian titanosaur sauropod dinosaur known from the Late Cretaceous of Chubut Province, southern Argentina. It contains a single species, Elaltitan lilloi.

Normanniasaurus is an extinct genus of basal titanosaur sauropod known from the Early Cretaceous Poudingue Ferrugineux of Seine-Maritime, northwestern France.

Lohuecotitan is an extinct genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur which lived during the Late Cretaceous in Spain. The only species known in the genus is Lohuecotitan pandafilandi, described and named in 2016.

Nullotitan is a genus of lithostrotian titanosaur from the Chorrillo Formation from Santa Cruz Province in Argentina. The type and only species is Nullotitan glaciaris. It was a contemporary of the ornithopod Isasicursor which was described in the same paper.

Ruixinia is an extinct genus of somphospondylan titanosauriform dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) Yixian Formation of China. The genus contains a single species, Ruixinia zhangi. The Ruixinia holotype is a partial articulated skeleton with the most complete series of caudal vertebrae known from any Asian titanosauriform.

Garumbatitan is an extinct genus of somphospondylan sauropod dinosaur from the Cretaceous Arcillas de Morella Formation of Spain. The genus contains a single species, G. morellensis, known from multiple partial skeletons.

Sidersaura is an extinct genus of rebbachisaurid sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Huincul Formation of Argentina. The genus contains a single species, S. marae, known from the remains of four individuals. Sidersaura represents one of the largest known rebbachisaurids.

Udelartitan is an extinct genus of saltasauroid titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Guichón Formation of Uruguay. The genus contains a single species, U. celeste, known from fragmentary remains of at least two individuals.