Related Research Articles

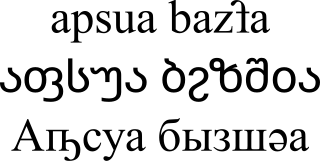

Abkhaz, also known as Abkhazian, is a Northwest Caucasian language most closely related to Abaza. It is spoken mostly by the Abkhaz people. It is one of the official languages of Abkhazia, where around 100,000 people speak it. Furthermore, it is spoken by thousands of members of the Abkhazian diaspora in Turkey, Georgia's autonomous republic of Adjara, Syria, Jordan, and several Western countries. 27 October is the day of the Abkhazian language in Georgia.

Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Persian grammar is the grammar of the Persian language, whose dialectal variants are spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, Caucasus, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It is similar to that of many other Indo-European languages. The language became a more analytic language around the time of Middle Persian, with fewer cases and discarding grammatical gender. The innovations remain in Modern Persian, which is one of the few Indo-European languages to lack grammatical gender, even in pronouns.

Judeo-Hamadani and Judeo-Borujerdi constitute a Northwestern Iranian language, originally spoken by the Iranian Jews of Hamadan and Borujerd in western Iran. Hamadanis refer to their language as ebri “Hebrew” or zabān-e qadim “old language.” Though not Hebrew, the term ebri is used to distinguish Judeo-Hamadani from Persian.

In 1920, Hamadan had around 13,000 Jewish residents. According to members of the community that Donald Stilo encountered in 2001-02, there were only eight people from the Jewish community left in Hamadān at the time, but others can still be found in Israel, New York City, and most predominantly in Los Angeles.

Judeo-Shirazi is a variety of Fars. Some Judeo-Shirazi speakers refer to the language as Jidi, though Jidi is normally a designation used by speakers of Judeo-Esfahani. It is spoken mostly by Persian Jews living in Shiraz and surrounding areas of the Fars Province in Iran.

Georgian grammar has many distinctive and extremely complex features, such as split ergativity and a polypersonal verb agreement system.

Vafsi is a dialect of the Tati language spoken in the Vafs village and surrounding area in the Markazi province of Iran. The dialects of the Tafresh region share many features with the Central Plateau dialects.

Talysh is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken in the northern regions of the Iranian provinces of Gilan and Ardabil and the southern regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan by around 500,000-800,000 people. Talysh language is closely related to the Tati language. It includes many dialects usually divided into three main clusters: Northern, Central (Iran) and Southern (Iran). Talysh is partially, but not fully, intelligible with Persian. Talysh is classified as "vulnerable" by UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.

This article describes the grammar of the standard Tajik language as spoken and written in Tajikistan. In general, the grammar of the Tajik language fits the analytical type. Little remains of the case system, and grammatical relationships are primarily expressed via clitics, word order and other analytical constructions. Like other modern varieties of Persian, Tajik grammar is almost identical to the classic Persian grammar, although there are differences in some verb tenses.

The Tati language is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken by the Tat people of Iran which is closely related to other languages such as Talysh, Mazandarani and Gilaki.

Kurdish grammar has many inflections, with prefixes and suffixes added to roots to express grammatical relations and to form words.

The verb is one of the most complex parts of Basque grammar. It is sometimes represented as a difficult challenge for learners of the language, and many Basque grammars devote most of their pages to lists or tables of verb paradigms. This article does not give a full list of verb forms; its purpose is to explain the nature and structure of the system.

The grammar of the Marathi language shares similarities with other modern Indo-Aryan languages such as Odia, Gujarati or Punjabi. The first modern book exclusively about the grammar of Marathi was printed in 1805 by Willam Carey.

Somali is an agglutinative language, using many affixes and particles to determine and alter the meaning of words. As in other related Afroasiatic languages, Somali nouns are inflected for gender, number and case, while verbs are inflected for persons, number, tenses, and moods.

Pashto is an S-O-V language with split ergativity. Adjectives come before nouns. Nouns and adjectives are inflected for gender (masc./fem.), number (sing./plur.), and case. The verb system is very intricate with the following tenses: Present; simple past; past progressive; present perfect; and past perfect. In any of the past tenses, Pashto is an ergative language; i.e., transitive verbs in any of the past tenses agree with the object of the sentence. The dialects show some non-standard grammatical features, some of which are archaisms or descendants of old forms.

Kho'ini is a Tatic dialect or language spoken in northwestern Iran, and is one of many Western Iranian languages. It is spoken in the village of Xoin and surrounding areas, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) southwest of Zanjan city in northern Iran. The Xoini verbal system follows the general pattern found in other Tati dialects. However, the dialect has its own special characteristics such as continuous present which is formed by the past stem, a preverb shift, and the use of connective sounds. The dialect is in danger of extinction.

Hindustani verbs conjugate according to mood, tense, person and number. Hindustani inflection is markedly simpler in comparison to Sanskrit, from which Hindustani has inherited its verbal conjugation system. Aspect-marking participles in Hindustani mark the aspect. Gender is not distinct in the present tense of the indicative mood, but all the participle forms agree with the gender and number of the subject. Verbs agree with the gender of the subject or the object depending on whether the subject pronoun is in the dative or ergative case or the nominative case.

Ubykh was a polysynthetic language with a high degree of agglutination that had an ergative-absolutive alignment.

Early Romani is the latest common predecessor of all forms of the Romani language. It was spoken before the Roma people dispersed throughout Europe. It is not directly attested, but rather reconstructed on the basis of shared features of existing Romani varieties. Early Romani is thought to have been spoken in the Byzantine Empire between the 9th-10th and 13th-14th centuries.

Judeo-Kashani ("Kashi") is a subvariety of Judeo-Iranian spoken by the Jews of Kashan (Kāšān). Diachronically, Judeo-Kashani is a Median language, belonging to the Kashanic branch of the Central Plateau Language Group spoken across Central Iran.

References

- 1 2 Jewish Languages Project.

- ↑ Endangered Language Alliance, Judeo-Isfahani.

- ↑ Linguists race the clock to save Iran’s dying Jewish languages.

- ↑ Endangered Languages Project, Judeo-Isfahani.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Borjian, Habib (2019). "Judeo-Isfahani: The Iranian Language of the Jews of Isfahan". Journal of Jewish Languages. 7 (2): 121–189. doi:10.1163/22134638-07021151. S2CID 214430375.

- ↑ Miller, Corey; Livingston, Jace; Vinson, Mark; Triebwasser Prado, Thomas (2014). Persian Dialects: As Spoken in Iran (PDF). University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language – via Department of Middle Eastern Studies, Charles University.