"Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit" is a Lutheran hymn, with words written by Martin Luther based on the Psalm 124. The hymn in three stanzas of seven lines each was first published in 1524. It was translated to English and has appeared in 20 hymnals. The hymn formed the base of several compositions, including chorale cantatas by Buxtehude and Bach.

Johann Sebastian Bach composed the church cantata Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild, BWV 79, in Leipzig in 1725, his third year as Thomaskantor, for Reformation Day and led the first performance on 31 October 1725.

Ludwig Helmbold, also spelled Ludwig Heimbold, was a poet of Lutheran hymns. He is probably best known for his hymn "Nun laßt uns Gott dem Herren", of which J. S. Bach used the fifth stanza for his cantata O heilges Geist- und Wasserbad, BWV 165; Bach also used his words in BWV 73, 79 and 186a.

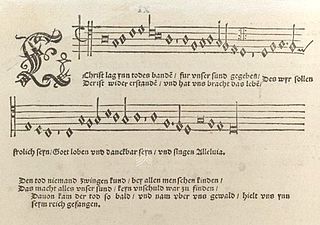

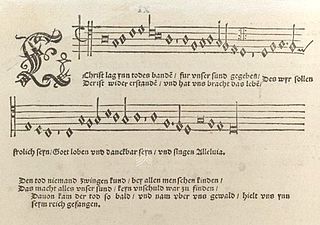

"Christ lag in Todesbanden" is an Easter hymn by Martin Luther. Its melody is by Luther and Johann Walter. Both the text and the melody were based on earlier examples. It was published in 1524 in the Erfurt Enchiridion and in Walter's choral hymnal Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn. Various composers, including Pachelbel, Bach and Telemann, have used the hymn in their compositions.

There are 52 chorale cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach surviving in at least one complete version. Around 40 of these were composed during his second year as Thomaskantor in Leipzig, which started after Trinity Sunday 4 June 1724, and form the backbone of his chorale cantata cycle. The eldest known cantata by Bach, an early version of Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, presumably written in 1707, was a chorale cantata. The last chorale cantata he wrote in his second year in Leipzig was Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1, first performed on Palm Sunday, 25 March 1725. In the ten years after that he wrote at least a dozen further chorale cantatas and other cantatas that were added to his chorale cantata cycle.

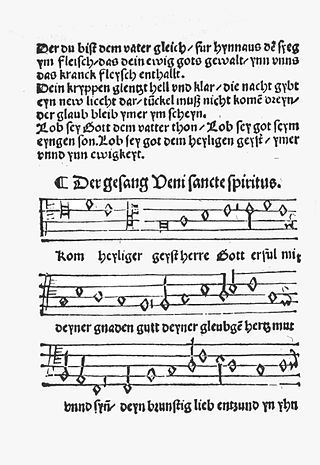

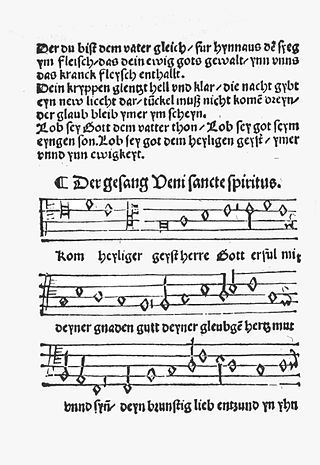

"Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott" is a Lutheran hymn for Pentecost, with words written by Martin Luther based on "Veni Sancte Spiritus, reple tuorum corda fidelium". The hymn in three stanzas was first published in 1524. For centuries the chorale has been the prominent hymn (Hauptlied) for Pentecost in German-speaking Lutheranism. Johann Sebastian Bach used it in several chorale preludes, cantatas and his motet Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, BWV 226.

"Vater unser im Himmelreich" is a Lutheran hymn in German by Martin Luther. He wrote the paraphrase of the Lord's Prayer in 1538, corresponding to his explanation of the prayer in his Kleiner Katechismus. He dedicated one stanza to each of the seven petitions and framed it with an opening and a closing stanza, each stanza in six lines. Luther revised the text several times, as extant manuscript show, concerned to clarify and improve it. He chose and possibly adapted an older anonymous melody, which was possibly associated with secular text, after he had first selected a different one. Other hymn versions of the Lord's Prayer from the 16th and 20th-century have adopted the same tune, known as "Vater unser" and "Old 112th".

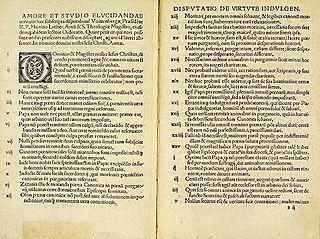

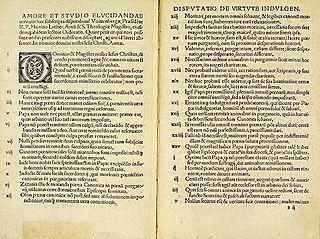

"Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der von uns den Gotteszorn wandt" is a Lutheran hymn in ten stanzas by Martin Luther for communion, first published in 1524 in the Erfurt Enchiridion. It is one of Luther's hymns which he wrote to strengthen his concepts of reformation. The models for the text and the melody of Luther's hymn existed in early 15th-century Bohemia. The text of the earlier hymn, "Jesus Christus nostra salus", goes back to the late 14th century. That hymn was embedded in a Hussite tradition.

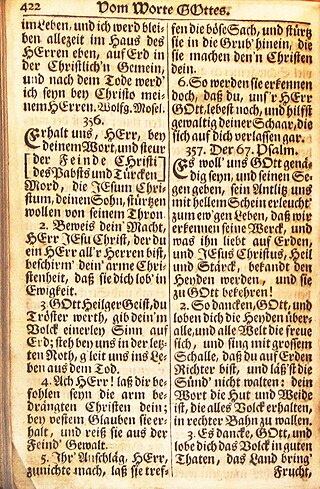

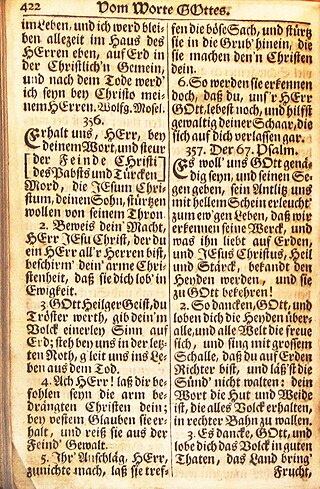

"Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort" is a Lutheran hymn by Martin Luther with additional stanzas by Justus Jonas, first published in 1542. It was used in several musical settings, including the chorale cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach, Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort, BWV 126.

"Gott sei gelobet und gebenedeiet" is a Lutheran hymn of 1524 with words written by Martin Luther who used an older first stanza and melody. It is a song of thanks after communion. Luther's version in three stanzas was printed in the Erfurt Enchiridion of 1524 and in Johann Walter's choral hymnal Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn the same year. Today, the song appears in German hymnals, including both the Protestant Evangelisches Gesangbuch, and in a different version in the Catholic Gotteslob.

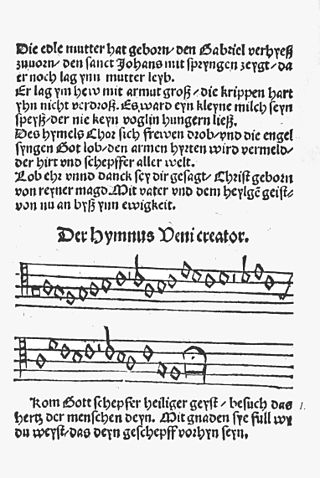

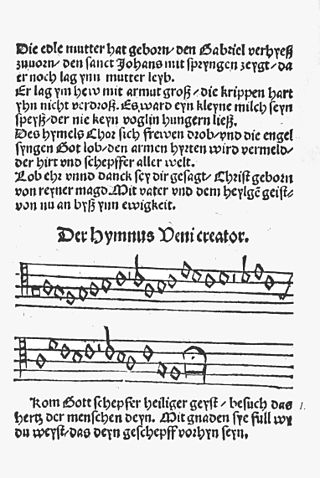

"Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist" is a Lutheran hymn for Pentecost, with words written by Martin Luther based on the Latin "Veni Creator Spiritus". The hymn in seven stanzas was first published in 1524. Its hymn tunes are Zahn No. 294, derived from the chant of the Latin hymn, and Zahn No. 295, a later transformation of that melody. The number in the current Protestant hymnal Evangelisches Gesangbuch (EG) is 126.

"Mitten wir im Leben sind mit dem Tod umfangen" is a Lutheran hymn, with words written by Martin Luther based on the Latin antiphon "Media vita in morte sumus". The hymn in three stanzas was first published in 1524. The hymn inspired composers from the Renaissance to contemporary to write chorale preludes and vocal compositions. Catherine Winkworth translated Luther's song to English in 1862. It has appeared in hymnals of various denominations.

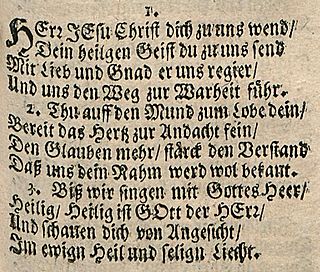

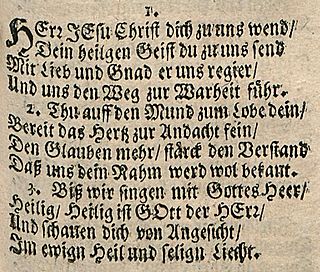

"Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend" is a Lutheran hymn from the 17th century. Its hymn tune, Zahn No. 624, was adopted in several compositions. It was translated into English and is part of modern hymnals, both Protestant and Catholic.

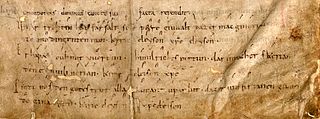

The Leise or Leis is a genre of vernacular medieval church song. They appear to have originated in the German-speaking regions, but are also found in Scandinavia, and are a precursor of Protestant church music.

"Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr" is an early Lutheran hymn, with text and melody attributed to Nikolaus Decius. With the reformers intending church service in German, it was intended as a German version of the Gloria part of the Latin mass, used in almost every service. Decius wrote three stanzas, probably in 1523, while a fourth was added, probably by Joachim Slüter.

"Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot" is a hymn by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther based on the Ten Commandments. It appeared first in 1524 in the Erfurt Enchiridion.

"Nun lasst uns Gott dem Herren" is a Lutheran hymn of 1575 with words by Ludwig Helmbold. It is a song of thanks, with the incipit: "Nun lasst uns Gott dem Herren Dank sagen und ihn ehren". The melody, Zahn No. 159, was published by Nikolaus Selnecker in 1587. The song appears in modern German hymnals, including in the Protestant Evangelisches Gesangbuch as EG 320.

"Ach lieben Christen seid getrost" is a Lutheran hymn in German with lyrics by Johannes Gigas, written in 1561. A penitential hymn, it was the basis for Bach's chorale cantata Ach, lieben Christen, seid getrost, BWV 114.

"Christ fuhr gen Himmel" is a German Ascension hymn. The church song is based the medieval melody of the Easter hymn "Christ ist erstanden". It was an ecumenical song from the beginning, with the first stanza published in 1480, then included in a Lutheran hymnal in 1545, and expanded by the Catholic Johannes Leisentritt in 1567. It appears in modern German Catholic and Protestant hymnals, and has inspired musical settings by composers from the 16th to the 21st century.

"Nun liebe Seel, nun ist es Zeit", alternatively written "Nun, liebe Seel, nun ist es Zeit", is a Lutheran hymn for Epiphany, in five stanzas of six lines each, by Georg Weissel. It was first printed in 1642, set as a motet by Johannes Eccard. A version with an additional stanza is attributed to Johann Christoph Arnschwanger.