Oneida County is a county in the state of New York, United States. As of February 26, 2024, the population was 226,654. The county seat is Utica. The name is in honor of the Oneida, one of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League or Haudenosaunee, which had long occupied this territory at the time of European encounter and colonization. The federally recognized Oneida Indian Nation has had a reservation in the region since the late 18th century, after the American Revolutionary War.

Utica is a city in the Mohawk Valley and the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most-populous city in New York State, its population was 65,283 in the 2020 U.S. Census. Located on the Mohawk River at the foot of the Adirondack Mountains, it is approximately 95 mi (153 km) west-northwest of Albany, 55 mi (89 km) east of Syracuse and 240 mi (386 km) northwest of New York City. Utica and the nearby city of Rome anchor the Utica–Rome Metropolitan Statistical Area comprising all of Oneida and Herkimer Counties.

Barneveld is a hamlet located within the Town of Trenton in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 284 at the 2010 census, when it was an incorporated village. The name is derived from the name of the Dutch statesman Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547–1619).

Clinton is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 1,942 at the 2010 census, declining to 1,683 in the 2020 census 13% decline). It was named for George Clinton, the first Governor of New York.

Marcy is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 8,777 at the 2020 census. The town was named after Governor William L. Marcy. It lies between the cities of Rome and Utica. The Erie Canal passes through the southern part of the town.

New York Mills is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 3,327 at the 2010 census.

Paris is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The town is in the southeast part of the county and is south of Utica. The population was 4,332 at the 2020 census. The town was named after an early benefactor, Colonel Isaac Paris.

Whitestown is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 18,667 at the 2010 census. The name is derived from Judge Hugh White, an early settler. The town is immediately west of Utica and the New York State Thruway passes across the town. The offices of the town of Whitestown are in the Village of Whitesboro.

Yorkville is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 2,689 at the 2010 census.

New Hartford is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 21,874. The name of New Hartford was provided by a settler family from Hartford, Connecticut.

New York State Route 5A (NY 5A) is an east–west state highway located within Oneida County, New York, in the United States. It is a 5.59-mile (9.0 km) alternate route of NY 5 between New Hartford and downtown Utica. At its eastern end, NY 5A becomes NY 5S at an interchange with Interstate 790 (I-790), NY 5, NY 8, and NY 12. The route is four lanes wide and passes through mostly commercial areas. When NY 5A was assigned in the mid-1930s, it ended at Yorkville, a village roughly midway between NY 5 in New Hartford and downtown Utica. It was extended to its present length in the 1940s.

New York State Route 840 (NY 840) is an east–west state highway located entirely within Oneida County, New York, in the United States. It is a 4.02-mile (6.47 km) superhighway extension of Judd Road, which ends at Halsey Road in Whitestown. The western terminus of NY 840 is at the junction of Judd and Halsey roads while its eastern terminus is at an interchange with the North–South Arterial near the southern city line of Utica. NY 840 opened to traffic in 2005, and the road was ceremoniously designated as the Officer Joseph D. Corr Memorial Highway in 2007. In 2008, part of Judd Road was redesignated as CR 840 to match the designation of its state highway continuation.

New York State Route 291 (NY 291) is a state highway in Oneida County, New York, in the United States. The route extends from an intersection with NY 69 in the town of Whitestown to a junction with NY 365 in the extreme northern tip of the town of Marcy, near the hamlet of Stittville. It is a two-lane highway its entire length. NY 291 meets NY 49, the Utica–Rome Expressway, at an interchange roughly 1 mile (1.6 km) northeast of NY 69. NY 291 provides access to the Marcy Correctional Facility and Mid-State Correctional Facility, both in Marcy.

The Utica–Rome Metropolitan Statistical Area, as defined by the United States Census Bureau, is an area consisting of two counties in Central New York anchored by the cities of Utica and Rome. As of the 2020 census, the MSA had a population of 292,264.

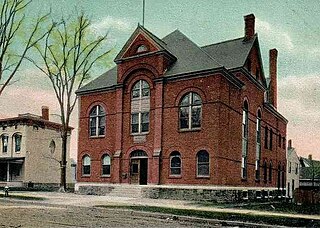

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at which black men were just as welcome as whites. "Oneida was the seed of Lane Seminary, Western Reserve College, Oberlin and Knox colleges."

This article on the demographics of Utica contains information on population characteristics of Utica, New York, including households, family status, age, gender, income, race and ethnicity.

Sauquoit Creek is a 17.0-mile-long (27.4 km) river in New York, United States. It lies within the southern part of Oneida County. The creek flows eastward, then turns sharply and flows generally northward through the Sauquoit Valley to the Mohawk River, entering the river on the east side of Whitesboro. It is therefore part of the Hudson River watershed.

Jedediah Sanger was the founder of the town of New Hartford, New York, United States. He was a native of Sherborn, Massachusetts, and the ninth child of Richard and Deborah Sanger, a prominent colonial New England family. During the Revolutionary War he attained the rank of 1st Lieutenant having fought in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Siege of Boston (1776), and during the New York Campaign.

Marianne Buttenschon is an American politician and educator from the state of New York. She is a member of the New York State Assembly, representing the 119th district.

Harry Sherburn Patten was an American lawyer and politician from New York.