Carbon is a chemical element; it has symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 electrons. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon makes up about 0.025 percent of Earth's crust. Three isotopes occur naturally, 12C and 13C being stable, while 14C is a radionuclide, decaying with a half-life of about 5,730 years. Carbon is one of the few elements known since antiquity.

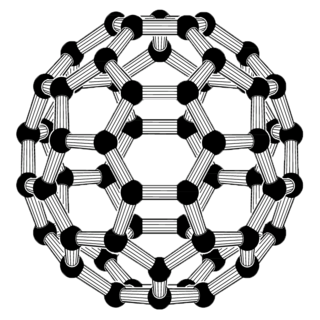

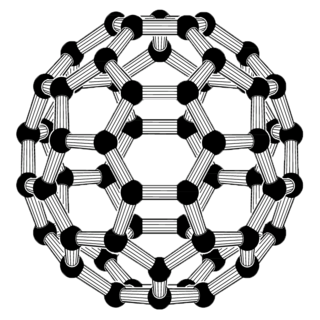

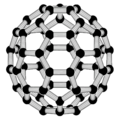

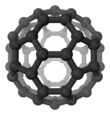

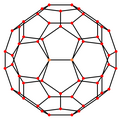

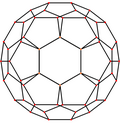

A fullerene is an allotrope of carbon whose molecules consist of carbon atoms connected by single and double bonds so as to form a closed or partially closed mesh, with fused rings of five to seven atoms. The molecules may have hollow sphere- and ellipsoid-like forms, tubes, or other shapes.

Sir Harold Walter Kroto was an English chemist. He shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Robert Curl and Richard Smalley for their discovery of fullerenes. He was the recipient of many other honors and awards.

Richard Errett Smalley was an American chemist who was the Gene and Norman Hackerman Professor of Chemistry, Physics, and Astronomy at Rice University. In 1996, along with Robert Curl, also a professor of chemistry at Rice, and Harold Kroto, a professor at the University of Sussex, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of a new form of carbon, buckminsterfullerene, also known as buckyballs. He was an advocate of nanotechnology and its applications.

Robert Floyd Curl Jr. was an American chemist who was Pitzer–Schlumberger Professor of Natural Sciences and professor of chemistry at Rice University. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996 for the discovery of the nanomaterial buckminsterfullerene, and hence the fullerene class of materials, along with Richard Smalley and Harold Kroto of the University of Sussex.

Diffuse interstellar bands (DIBs) are absorption features seen in the spectra of astronomical objects in the Milky Way and other galaxies. They are caused by the absorption of light by the interstellar medium. Circa 500 bands have now been seen, in ultraviolet, visible and infrared wavelengths.

Dodecahedrane is a chemical compound, a hydrocarbon with formula C20H20, whose carbon atoms are arranged as the vertices (corners) of a regular dodecahedron. Each carbon is bound to three neighbouring carbon atoms and to a hydrogen atom. This compound is one of the three possible Platonic hydrocarbons, the other two being cubane and tetrahedrane.

Endohedral fullerenes, also called endofullerenes, are fullerenes that have additional atoms, ions, or clusters enclosed within their inner spheres. The first lanthanum C60 complex called La@C60 was synthesized in 1985. The @ (at sign) in the name reflects the notion of a small molecule trapped inside a shell. Two types of endohedral complexes exist: endohedral metallofullerenes and non-metal doped fullerenes.

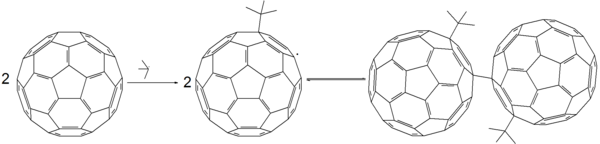

The Bingel reaction in fullerene chemistry is a fullerene cyclopropanation reaction to a methanofullerene first discovered by C. Bingel in 1993 with the bromo derivative of diethyl malonate in the presence of a base such as sodium hydride or DBU. The preferred double bonds for this reaction on the fullerene surface are the shorter bonds at the junctions of two hexagons and the driving force is relief of steric strain.

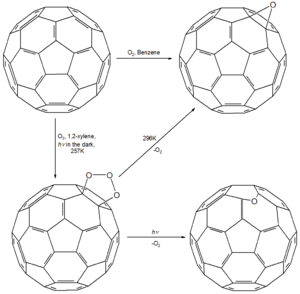

Fullerene chemistry is a field of organic chemistry devoted to the chemical properties of fullerenes. Research in this field is driven by the need to functionalize fullerenes and tune their properties. For example, fullerene is notoriously insoluble and adding a suitable group can enhance solubility. By adding a polymerizable group, a fullerene polymer can be obtained. Functionalized fullerenes are divided into two classes: exohedral fullerenes with substituents outside the cage and endohedral fullerenes with trapped molecules inside the cage.

The history of nanotechnology traces the development of the concepts and experimental work falling under the broad category of nanotechnology. Although nanotechnology is a relatively recent development in scientific research, the development of its central concepts happened over a longer period of time. The emergence of nanotechnology in the 1980s was caused by the convergence of experimental advances such as the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope in 1981 and the discovery of fullerenes in 1985, with the elucidation and popularization of a conceptual framework for the goals of nanotechnology beginning with the 1986 publication of the book Engines of Creation. The field was subject to growing public awareness and controversy in the early 2000s, with prominent debates about both its potential implications as well as the feasibility of the applications envisioned by advocates of molecular nanotechnology, and with governments moving to promote and fund research into nanotechnology. The early 2000s also saw the beginnings of commercial applications of nanotechnology, although these were limited to bulk applications of nanomaterials rather than the transformative applications envisioned by the field.

James R. Heath is an American chemist and the president and professor of Institute of Systems Biology. Previous to this, he was the Elizabeth W. Gilloon Professor of Chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, after having moved from University of California Los Angeles.

The Drexler–Smalley debate on molecular nanotechnology was a public dispute between K. Eric Drexler, the originator of the conceptual basis of molecular nanotechnology, and Richard Smalley, a recipient of the 1996 Nobel prize in Chemistry for the discovery of the nanomaterial buckminsterfullerene. The dispute was about the feasibility of constructing molecular assemblers, which are molecular machines which could robotically assemble molecular materials and devices by manipulating individual atoms or molecules. The concept of molecular assemblers was central to Drexler's conception of molecular nanotechnology, but Smalley argued that fundamental physical principles would prevent them from ever being possible. The two also traded accusations that the other's conception of nanotechnology was harmful to public perception of the field and threatened continued public support for nanotechnology research.

C70 fullerene is the fullerene molecule consisting of 70 carbon atoms. It is a cage-like fused-ring structure which resembles a rugby ball, made of 25 hexagons and 12 pentagons, with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge. A related fullerene molecule, named buckminsterfullerene (or C60 fullerene) consists of 60 carbon atoms.

A transition metal fullerene complex is a coordination complex wherein fullerene serves as a ligand. Fullerenes are typically spheroidal carbon compounds, the most prevalent being buckminsterfullerene, C60.

Azafullerenes are a class of heterofullerenes in which the element substituting for carbon is nitrogen. They can be in the form of a hollow sphere, ellipsoid, tube, and many other shapes. Spherical azafullerenes resemble the balls used in football (soccer). They are also a member of the carbon nitride class of materials that include beta carbon nitride (β-C3N4), predicted to be harder than diamond. Besides the pioneering work of a couple of academic groups, this class of compounds has so far garnered little attention from the broader fullerene research community. Many properties and structures are yet to be discovered for the highly-nitrogen substituted subset of molecules.

Heterofullerenes are classes of fullerenes, at least one carbon atom is replaced by another element. Based on spectroscopy, substitutions have been reported with boron (borafullerenes), nitrogen (azafullerenes), oxygen, arsenic, germanium, phosphorus, silicon, iron, copper, nickel, rhodium and iridium. Reports on isolated heterofullerenes are limited to those based on nitrogen and oxygen.

Konstantinos Fostiropoulos is a Greek physicist who has been working in Germany in the areas nano-materials, solid-state physics, molecular physics, astrophysics, and thermodynamics. From 2003 to 2016 he has been founder and head of the Organic Solar Cells Group at the Institute Heterogeneous Materials Systems within the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin. His scientific works include novel energy materials and photovoltaic device concepts, carbon clusters in the Interstellar Medium, and intermolecular forces of real gases.

Neon compounds are chemical compounds containing the element neon (Ne) with other molecules or elements from the periodic table. Compounds of the noble gas neon were believed not to exist, but there are now known to be molecular ions containing neon, as well as temporary excited neon-containing molecules called excimers. Several neutral neon molecules have also been predicted to be stable, but are yet to be discovered in nature. Neon has been shown to crystallize with other substances and form clathrates or Van der Waals solids.

The solubility of fullerenes is generally low. Carbon disulfide dissolves 8g/L of C60, and the best solvent (1-chloronaphthalene) dissolves 53 g/L. up Still, fullerenes are the only known allotrope of carbon that can be dissolved in common solvents at room temperature. Besides those two, good solvents for fullerenes include 1,2-dichlorobenzene, toluene, p-xylene, and 1,2,3-tribromopropane. Fullerenes are highly insoluble in water, and practically insoluble in methanol.

![A C62 derivative [C62(C6H4-4-Me)2] synthesized from C60 and 3,6-bis(4-methylphenyl)-3,6-dihydro-1,2,4,5-tetrazine 3D structure of C62 derivative from C60 update.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/3D_structure_of_C62_derivative_from_C60_update.jpg/220px-3D_structure_of_C62_derivative_from_C60_update.jpg)