Thomas Newcomen was an English inventor who created the atmospheric engine, the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. He was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling.

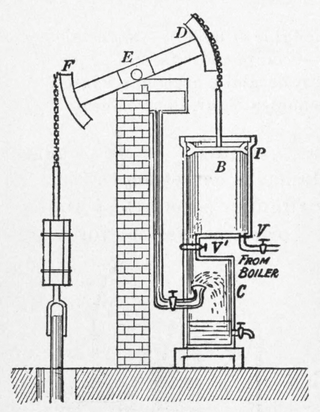

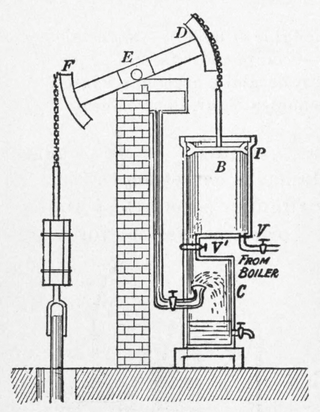

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creating a partial vacuum which allowed the atmospheric pressure to push the piston into the cylinder. It was historically significant as the first practical device to harness steam to produce mechanical work. Newcomen engines were used throughout Britain and Europe, principally to pump water out of mines. Hundreds were constructed throughout the 18th century.

The Watt steam engine design became synonymous with steam engines, and it was many years before significantly new designs began to replace the basic Watt design.

The Metropolitan Borough of Tameside is a metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester in England. It is named after the River Tame, which flows through the borough, and covers the towns of Ashton-under-Lyne, Audenshaw, Denton, Droylsden, Dukinfield, Hyde, Mossley and Stalybridge. Tameside is bordered by the metropolitan boroughs of Stockport to the south, Oldham to the north and northeast, Manchester to the west, and to the east by the Borough of High Peak in Derbyshire. As of 2011 the overall population was 219,324. It is also the 8th-most populous borough of Greater Manchester by population.

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. The population was 48,604 at the 2021 census. Historically in Lancashire, it is on the north bank of the River Tame, in the foothills of the Pennines, 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Manchester.

Elsecar is a village in the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley in South Yorkshire, England. It is near to Jump and Wentworth, it is also 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Hoyland, 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Barnsley and 8 miles (13 km) north-east of Sheffield. Elsecar falls within the Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Ward of Hoyland Milton.

The Hollinwood Branch Canal was a canal near Hollinwood, in Oldham, England. It left the main line of the Ashton Canal at Fairfield Junction immediately above lock 18. It was just over 4.5 miles (7.2 km) long and went through Droylsden and Waterhouses to terminate at Hollinwood Basin. It rose through four locks at Waterhouses (19–22) and another four at Hollinwood (23–26). Immediately above lock 22 at Waterhouses was Fairbottom Junction where the Fairbottom Branch Canal started. Beyond Hollinwood Basin there was a lock free private branch, known as the Werneth Branch Canal, to Old Lane Colliery, which opened in 1797. It is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Local Nature Reserve.

The Fairbottom Branch Canal was a canal near Ashton-under-Lyne in Greater Manchester, England.

A beam engine is a type of steam engine where a pivoted overhead beam is used to apply the force from a vertical piston to a vertical connecting rod. This configuration, with the engine directly driving a pump, was first used by Thomas Newcomen around 1705 to remove water from mines in Cornwall. The efficiency of the engines was improved by engineers including James Watt, who added a separate condenser; Jonathan Hornblower and Arthur Woolf, who compounded the cylinders; and William McNaught, who devised a method of compounding an existing engine. Beam engines were first used to pump water out of mines or into canals but could be used to pump water to supplement the flow for a waterwheel powering a mill.

Wet Earth Colliery was a coal mine located on the Manchester Coalfield, in Clifton, Greater Manchester. The colliery site is now the location of Clifton Country Park. The colliery has a unique place in British coal mining history; apart from being one of the earliest pits in the country, it is the place where engineer James Brindley made water run uphill.

The Anson Engine Museum is situated on the site of the old Anson colliery in Poynton, Cheshire, England. It is the work of Les Cawley and Geoff Challinor who began collecting and showing stationary engines for a hobby. The museum now has one of the largest collections of engines in Europe. The museum site also includes a working blacksmith's smithy and carpentry shop and a café.

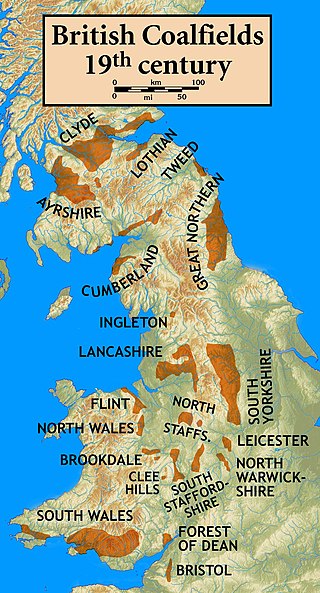

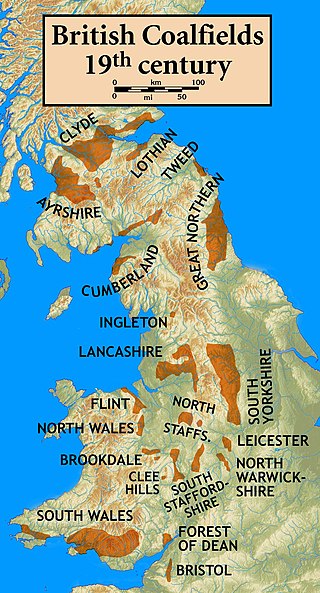

The Lancashire Coalfield in North West England was an important British coalfield. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago.

Old Bess is an early beam engine built by the partnership of Boulton and Watt. The engine was constructed in 1777 and worked until 1848.

A water-returning engine was an early form of stationary steam engine, developed at the start of the Industrial Revolution in the middle of the 18th century. The first beam engines did not generate power by rotating a shaft but were developed as water pumps, mostly for draining mines. By coupling this pump with a water wheel, they could be used to drive machinery.

The Oldham Coalfield is the most easterly part of the South Lancashire Coalfield. Its coal seams were laid down in the Carboniferous period and some easily accessible seams were worked on a small scale from the Middle Ages and extensively from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century until the middle of the 20th century.

Calvert's Engine or the Newbridge Colliery Engine is a beam engine of 1845, now preserved on the campus of the University of Glamorgan, South Wales.

The Newcomen Memorial Engine is a preserved beam engine in Dartmouth, Devon. It was preserved as a memorial to Thomas Newcomen, inventor of the beam engine, who was born in Dartmouth.

The Blacksyke Tower, Blacksyke Engine House, Caprington Colliery Engine House or even Lusk's Folly is a Scheduled Monument associated with a double lime kiln complex in the Parish of Riccarton and is a building of national importance. The Blacksyke site is a significant survival of early coal and lime industries. The engine house's mock Gothic tower house style is very unusual and rare survival of its type. This late-18th-century engine house would be one of the oldest surviving examples of its kind in the United Kingdom. The track bed of the wagonway and several sidings that linked the complex with the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway can still be clearly made out.

Earlston is a hamlet in Riccarton, East Ayrshire, Scotland. The habitation dates from at least the early 18th century and is near Caprington Castle and Todrigs Mill. It was for many years the site of a large sawmill and a mine pumping engine, and had sidings of the Glasgow and South-Western Railway's Fairlie Branch.

The Wanlockhead beam engine is located close to the Wanlock Water below Church Street on the B797 in the village of Wanlockhead, Parish of Sanquhar, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. The site is in the Lowther Hills above the Mennock Pass, a mile south of Leadhills in the Southern Uplands. This is the only remaining original water powered beam engine in the United Kingdom and still stands at its original location. It ceased working circa 1910 after installation circa 1870.