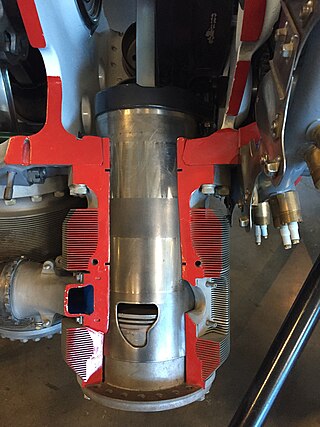

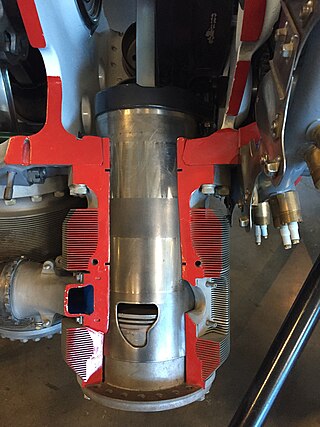

The sleeve valve is a type of valve mechanism for piston engines, distinct from the usual poppet valve. Sleeve valve engines saw use in a number of pre–World War II luxury cars and in the United States in the Willys-Knight car and light truck. They subsequently fell from use due to advances in poppet-valve technology, including sodium cooling, and the Knight system double sleeve engine's tendency to burn a lot of lubricating oil or to seize due to lack of it. The Scottish Argyll company used its own, much simpler and more efficient, single sleeve system (Burt-McCollum) in its cars, a system which, after extensive development, saw substantial use in British aircraft engines of the 1940s, such as the Napier Sabre, Bristol Hercules, Centaurus, and the promising but never mass-produced Rolls-Royce Crecy, only to be supplanted by the jet engines.

A camshaft is a shaft that contains a row of pointed cams, in order to convert rotational motion to reciprocating motion. Camshafts are used in piston engines, mechanically controlled ignition systems and early electric motor speed controllers.

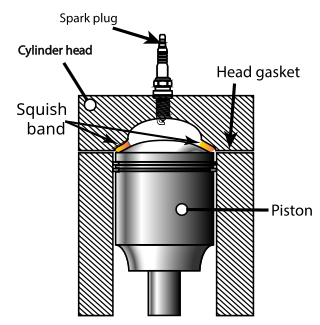

In an internal combustion engine, the cylinder head sits above the cylinders and forms the roof of the combustion chamber. In sidevalve engines, the head is a simple sheet of metal; whereas in more modern overhead valve and overhead camshaft engines, the cylinder head is a more complicated block often containing inlet and exhaust passages, coolant passages, valves, camshafts, spark plugs and fuel injectors. Most straight engines have a single cylinder head shared by all of the cylinders and most V engines have two cylinder heads.

A combustion chamber is part of an internal combustion engine in which the fuel/air mix is burned. For steam engines, the term has also been used for an extension of the firebox which is used to allow a more complete combustion process.

The valve gear of a steam engine is the mechanism that operates the inlet and exhaust valves to admit steam into the cylinder and allow exhaust steam to escape, respectively, at the correct points in the cycle. It can also serve as a reversing gear. It is sometimes referred to as the "motion".

Variable valve timing (VVT) is the process of altering the timing of a valve lift event in an internal combustion engine, and is often used to improve performance, fuel economy or emissions. It is increasingly being used in combination with variable valve lift systems. There are many ways in which this can be achieved, ranging from mechanical devices to electro-hydraulic and camless systems. Increasingly strict emissions regulations are causing many automotive manufacturers to use VVT systems.

An overhead camshaft (OHC) engine is a piston engine in which the camshaft is located in the cylinder head above the combustion chamber. This contrasts with earlier overhead valve engines (OHV), where the camshaft is located below the combustion chamber in the engine block.

An overhead valve (OHV) engine, sometimes called a pushrod engine, is a piston engine whose valves are located in the cylinder head above the combustion chamber. This contrasts with flathead engines, where the valves were located below the combustion chamber in the engine block.

A rotary valve is a type of valve in which the rotation of a passage or passages in a transverse plug regulates the flow of liquid or gas through the attached pipes. The common stopcock is the simplest form of rotary valve. Rotary valves have been applied in numerous applications, including:

A flathead engine, also known as a sidevalve engine or valve-in-block engine, is an internal combustion engine with its poppet valves contained within the engine block, instead of in the cylinder head, as in an overhead valve engine.

A tappet is a valve train component which converts rotating motion into linear motion in activating a valve. It is most commonly found in internal combustion engines, which converts the rotating motion of the camshaft into linear motion of intake and exhaust valves, either directly or indirectly.

In a piston engine, the valve timing is the precise timing of the opening and closing of the valves. In an internal combustion engine those are usually poppet valves and in a steam engine they are usually slide valves or piston valves.

A valvetrain or valve train is a mechanical system that controls the operation of the intake and exhaust valves in an internal combustion engine. The intake valves control the flow of air/fuel mixture into the combustion chamber, while the exhaust valves control the flow of spent exhaust gasses out of the combustion chamber once combustion is completed.

The intake/inlet over exhaust, or "IOE" engine, known in the US as F-head, is a four-stroke internal combustion engine whose valvetrain comprises OHV inlet valves within the cylinder head and exhaust side-valves within the engine block.

The uniflow type of steam engine uses steam that flows in one direction only in each half of the cylinder. Thermal efficiency is increased by having a temperature gradient along the cylinder. Steam always enters at the hot ends of the cylinder and exhausts through ports at the cooler centre. By this means, the relative heating and cooling of the cylinder walls is reduced.

The double-beat valve, drop valve or equilibrium valve is a type of poppet valve arranged to allow it to be opened against a high pressure with a minimum of force. One of its uses is in steam engines to admit steam to the cylinders and to release the exhaust. In stationary steam engines it is usually operated by trip valve gear while in railway locomotives a valve gear such as Caprotti is used.

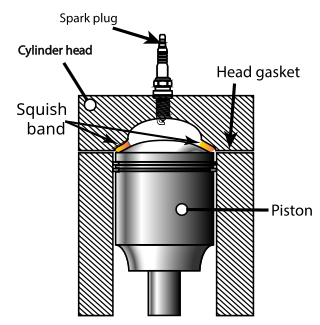

Squish is an effect in internal combustion engines which creates sudden turbulence of the air-fuel mixture as the piston approaches top dead centre (TDC).

An internal combustion engine is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal combustion engine, the expansion of the high-temperature and high-pressure gases produced by combustion applies direct force to some component of the engine. The force is typically applied to pistons, turbine blades, a rotor, or a nozzle. This force moves the component over a distance, transforming chemical energy into kinetic energy which is used to propel, move or power whatever the engine is attached to.

The five-stroke engine is a compound internal combustion engine patented by Gerhard Schmitz in 2000. Schmitz's concept is being developed by Ilmor Engineering. Ilmor's prototype is an internal combustion engine that uses a solid cylinder block with electric motors driving the oil and water cooling pumps. The prototype uses two overhead camshafts with standard poppet valves. The five-stroke prototype engine is turbocharged. The goal of the five-stroke engine is to have higher efficiency with lower fuel use. In order to increase efficiency, a secondary cylinder is added as an expansion processor to extract more energy from the fuel.