James Watt was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fundamental to the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution in both his native Great Britain and the rest of the world.

Thomas Newcomen was an English inventor who created the atmospheric engine, the first practical fuel-burning engine in 1712. He was an ironmonger by trade and a Baptist lay preacher by calling.

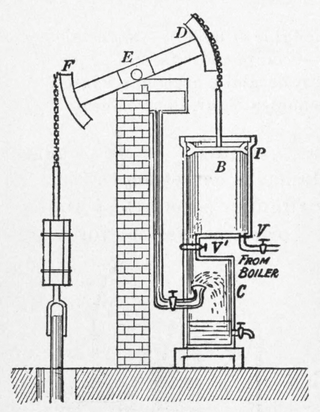

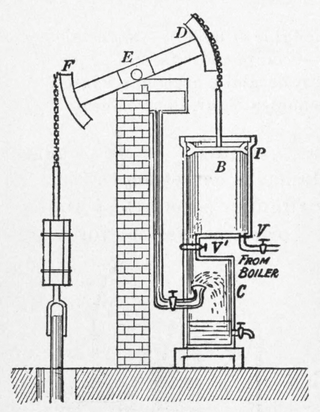

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creating a partial vacuum which allowed the atmospheric pressure to push the piston into the cylinder. It was historically significant as the first practical device to harness steam to produce mechanical work. Newcomen engines were used throughout Britain and Europe, principally to pump water out of mines. Hundreds were constructed throughout the 18th century.

The Watt steam engine design became synonymous with steam engines, and it was many years before significantly new designs began to replace the basic Watt design.

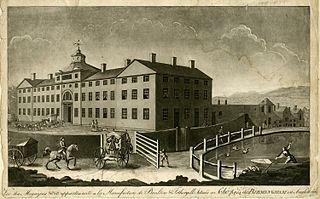

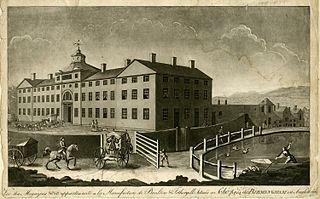

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the English manufacturer Matthew Boulton and the Scottish engineer James Watt, the firm had a major role in the Industrial Revolution and grew to be a major producer of steam engines in the 19th century.

The Smethwick Engine is a Watt steam engine made by Boulton and Watt, which was installed near Birmingham, England, and was brought into service in May 1779. Now at Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, it is the oldest working steam engine and the oldest working engine in the world.

The Soho Manufactory was an early factory which pioneered mass production on the assembly line principle, in Soho, Birmingham, England, at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. It operated from 1766–1848 and was demolished in 1853.

Stationary steam engines are fixed steam engines used for pumping or driving mills and factories, and for power generation. They are distinct from locomotive engines used on railways, traction engines for heavy steam haulage on roads, steam cars, agricultural engines used for ploughing or threshing, marine engines, and the steam turbines used as the mechanism of power generation for most nuclear power plants.

Steam power developed slowly over a period of several hundred years, progressing through expensive and fairly limited devices in the early 17th century, to useful pumps for mining in 1700, and then to Watt's improved steam engine designs in the late 18th century. It is these later designs, introduced just when the need for practical power was growing due to the Industrial Revolution, that truly made steam power commonplace.

Improvements to the steam engine were some of the most important technologies of the Industrial Revolution, although steam did not replace water power in importance in Britain until after the Industrial Revolution. From Englishman Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric engine, of 1712, through major developments by Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer James Watt, the steam engine began to be used in many industrial settings, not just in mining, where the first engines had been used to pump water from deep workings. Early mills had run successfully with water power, but by using a steam engine a factory could be located anywhere, not just close to a water source. Water power varied with the seasons and was not always available.

A beam engine is a type of steam engine where a pivoted overhead beam is used to apply the force from a vertical piston to a vertical connecting rod. This configuration, with the engine directly driving a pump, was first used by Thomas Newcomen around 1705 to remove water from mines in Cornwall. The efficiency of the engines was improved by engineers including James Watt, who added a separate condenser; Jonathan Hornblower and Arthur Woolf, who compounded the cylinders; and William McNaught, who devised a method of compounding an existing engine. Beam engines were first used to pump water out of mines or into canals but could be used to pump water to supplement the flow for a waterwheel powering a mill.

A Cornish engine is a type of steam engine developed in Cornwall, England, mainly for pumping water from a mine. It is a form of beam engine that uses steam at a higher pressure than the earlier engines designed by James Watt. The engines were also used for powering man engines to assist the underground miners' journeys to and from their working levels, for winching materials into and out of the mine, and for powering on-site ore stamping machinery.

The first recorded rudimentary steam engine was the aeolipile mentioned by Vitruvius between 30 and 15 BC and, described by Heron of Alexandria in 1st-century Roman Egypt. Several steam-powered devices were later experimented with or proposed, such as Taqi al-Din's steam jack, a steam turbine in 16th-century Ottoman Egypt, and Thomas Savery's steam pump in 17th-century England. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric engine became the first commercially successful engine using the principle of the piston and cylinder, which was the fundamental type of steam engine used until the early 20th century. The steam engine was used to pump water out of coal mines.

The Whitbread Engine preserved in the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, Australia, built in 1785, is one of the first rotative steam engines ever built, and is the oldest surviving. A rotative engine is a type of beam engine where the reciprocating motion of the beam is converted to rotary motion, producing a continuous power source suitable for driving machinery.

A water-returning engine was an early form of stationary steam engine, developed at the start of the Industrial Revolution in the middle of the 18th century. The first beam engines did not generate power by rotating a shaft but were developed as water pumps, mostly for draining mines. By coupling this pump with a water wheel, they could be used to drive machinery.

A cataract was a speed governing device used for early single-acting beam engines, particularly atmospheric engines and Cornish engines. It was a kind of water clock.

Resolution was an early beam engine, installed between 1781 and 1782 at Coalbrookdale as a water-returning engine to power the blast furnaces and ironworks there. It was one of the last water-returning engines to be constructed, before the rotative beam engine made this type of engine obsolete.

The Newcomen Memorial Engine is a preserved beam engine in Dartmouth, Devon. It was preserved as a memorial to Thomas Newcomen, inventor of the beam engine, who was born in Dartmouth.

The Lap Engine is a beam engine designed by James Watt, built by Boulton and Watt in 1788. It is now preserved at the Science Museum, London.