The geography of southern California refers to the geography of southern California in the United States.

The geography of southern California refers to the geography of southern California in the United States.

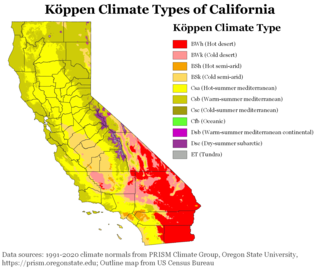

Despite the popular image of California as a place of sunshine and perfect weather, the local climate can be very diverse, with some areas experiencing more extreme conditions. However, the weather in the region is usually mild, especially in the winter, and dry, with rainfall ranging from moderate in the coastal regions to almost none at all in the desert. [1]

Around the coastal areas, the weather does not vary as dramatically as it does inland. Climate is affected by factors such as latitude, topography, and proximity to water masses - primarily the Pacific Ocean, and southern California's mountain ranges. The Transverse Ranges and the Peninsular Ranges are key players in the region's climate.

Essentially, the mountain ranges separate southern California into two distinct climatic regions: The heavy-populated coastal area west of these mountains is the one most associated with the term "southern California" and is characterized by pleasant weather all-year round, without frequent heat spells in the summer and without low temperatures in winter. By comparison, the area east of the ranges, between the mountains and the borders with Nevada and Arizona, is dominated by the Sonoran Desert and the Mojave Desert and tends to be more arid and register more extreme temperatures in both summer and winter. [2]

This is a common weather prediction for southern California. Due to the topographic features and proximity to the Pacific, southern California has its share of both low clouds and fog. [3]

Coastal fogs are frequently generated by interaction between seasonal inversion layers and the coastal marine layer, and may reach as far inland as 20 miles, butting up against inland mountains or coastal mountain ranges. While fog generally is the collection of water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface, southern California's fog varies from the light 'ground fogs' to a dense almost "Tule fog" (pronounced ˈtuːliː fog) in the Winter and Spring, depending on the interaction of cold air brought down from the local mountains and the warmer ocean air masses.

However, over the last few decades, clouds have become less prevalent on the coast, due to urban heat and climate change. [4] When compared with data from the 1970s, scientists discovered that the stratus cloud cover has decreased between 25% and 50%. [5]

In contrast with the sunny summer, late spring in southern California is often overcast. This period, known to the locals as "May Gray" and "June Gloom", dims the coastal skies of sunny southern California. [6] During this time, the coastal clouds may remain all day, but often give way to some hazy afternoon sunshine. The number of gloomy days during this period vary from year to year. Years with warmer ocean temperatures, influenced by the broader El Niño weather pattern, may result in fewer gray days in June, whereas the cooler ocean temperatures associated with a La Niña pattern, usually foretell more gray days in the season. [7]

Because of the hot, dry and windy nature of southern California, wildfires are common. [8] While most of them only affect small areas, wildfire can quickly get out of control and spread across large areas of woodland, particularly when fanned by the Santa Ana winds. [9] [10] Hot and extremely dry, they are also known as "Devil winds", and descend on the coastal region from the continental interior of the American West, increasing in temperature as they approach the ocean. [11] [12]

Because natural wildfires are more likely to appear towards the end of long, dry summers, they have become a more serious problem in recent years because of climate change, which makes wildfires increasingly larger and more frequent. [13] Climate change has also widened the wildfire "season" from a few summer months to virtually the entire year. [14] At the same time, climate scientists are expecting that climate change will diminish the strength of the Santa Ana winds, potentially limiting its role in spreading wildfires. [15]

Other than the Pacific Coast, the Transverse Ranges and the Peninsular Ranges are the two most important physical landscapes in the region. Both ranges have their particular characteristics, from the trend of the mountains, to the different climates within each range.

The Transverse Ranges is a unique set of mountain ranges in California. They are the only mountain ranges that run west to east, as opposed to the rest of California’s ranges that run north to south. [16] These mountain ranges run from Santa Barbara County into San Bernardino County. They derive the name Transverse Ranges due to their east-west orientation, making them transverse to the general north-south orientation of most of California's coastal mountain ranges. [17]

The Transverse Ranges experience temperature differences from winter to summer of about 36 °F (20 °C). One factor contributing to this variability is the distance from the ocean: the eastern part of the Transverse Ranges is furthest from the coast and has the most drastic temperature variation, whereas the western part is closest to the ocean and therefore has less variance. [18]

The amount of precipitation of any area is affected by elevation, and topography influences temperature within elevation ranges. The higher the elevation, the lower the temperatures, and with lower temperatures come increased precipitation. The highest point of the Ranges is Mt. San Gorgonio (11,503 feet) in the San Bernardino Mountains at the eastern end of the Ranges. [19] The southeastern part of the Transverse Ranges can be considered to have a desert climate. Mountain ranges can cause a rain shadow effect, when air flow inland from the ocean and it rises, it begins to cool and after it reaches the other side of the mountain it becomes warm and evaporates. [20] This is one of the reasons for the dry conditions in the Transverse Ranges that are furthest from the coast. [21] The Ranges are also affected by the Santa Ana winds, a regional wind system created when air is forced from a high pressure to a low pressure, causing air to move from inland towards the ocean. These dry winds usually originate at the eastern end of the Ranges. [9]

The San Andreas Fault and many other faults run through the Transverse Ranges. Because of this, this area is one of the most geologically active regions in California, with surface changes from fractions of an inch to six feet. [22] Sedimentary rocks from the late Mesozoic era and early Cenozoic era are found in the western part of the region. Near the eastern ranges, such as the San Bernardino Mountains, metamorphic rocks that resemble rocks of the Sierra Nevada can be found. [23] [24]

These east-to-west running ranges include a variety of different mountains. Some mountains are steep like the San Gabriel Mountains. Other areas of the Transverse Ranges have a very low elevation like the Mojave Desert. The mountains ranges comprising the Transverse ranges include: [25]

People have taken full advantage of the Transverse Ranges. The Ranges create a number of coastal plains and valleys which have become densely populated because of their prime living conditions. These valleys include Oxnard Plain, San Fernando Valley, Simi Valley, San Gabriel Valley, and the Inland Valley. The mountain ranges create recreation and living areas and have several ski resorts and provide several hiking and off-road vehicle use areas. Many people reside in the hills of the Transverse Ranges, where they may work locally or commute to work in more populated areas 'down the hill.' Such communities provide an alternative to city and suburban living in southern California.

The Peninsular Ranges are a group of mountain ranges in the Pacific Coast Ranges, which stretch over 900 miles from southern California in the United States to the southern tip of Mexico's Baja California peninsula. [26] They are part of the North American Coast Ranges that run along the Pacific coast from Alaska to Mexico. [27] Elevations range from 500 ft to 11,500 ft (150 m to 3,500 m) and vegetation in these ranges varies from coastal sage scrub to chaparral, and from oak woodland to conifer forest.

The Peninsular Ranges of southern California include the Santa Ana Mountains, San Jacinto Mountains, and the Laguna Mountains. [28] The Peninsular Ranges of Baja California include the Sierra Juarez, Sierra San Pedro Martir, Sierra de la Giganta, and Sierra de la Laguna. These ranges run from north to south. [29]

The Santa Ana Mountains are the largest natural landscape along the coast of southern California. These mountains peak at about 5,689 feet, on Santiago Peak. [30] This range starts in the north, in the Corona area heading southeast of the Puente Hills region.

The San Jacinto Mountains are located in the desert areas in the north and east side of southern California. They peak at about 10,833 feet. [31] They run from the San Bernardino Mountains southeast to the Santa Rosa Mountains. This mountain range is the northernmost part of the Peninsular Range.

The Santa Rosa Mountains are located at the southern end of the San Jacinto Mountains, where they connect to it. The range extends for approximately 30 miles (48 km) through Riverside, San Diego and Imperial counties, along the western side of the Coachella Valley, where they bound the Anza-Borrego portion of the Colorado Desert. The highest peak in the range is Toro Peak (8,717 feet). [32]

The Laguna Mountains are located in the eastern part of San Diego County. They range northwest to southeast for approximately 20 miles and peak at Cuyapaipe Mountain (6,378 feet). [33] These mountains extend northwest about 35 mi (56 km) from the Mexican border at the Sierra de Juárez. The Sonora Desert lies to the east and the Santa Rosa Mountains are to the northwest.

As with the Transverse Ranges, areas along the coast tend to have less temperature variation than do inland areas. The Peninsular Ranges also form a rain shadow on the Colorado Desert region of California and on much of the larger Sonora Desert. [34] The ranges are affected by the marine layer that provides cooling temperatures and fog, and rainfall varies seasonally with tropical storm activity.

Chaparral is a shrubland plant community found primarily in California, in southern Oregon and in the northern portion of the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico. It is shaped by a Mediterranean climate and infrequent, high-intensity crown fires.

California is a U.S. state on the western coast of North America. Covering an area of 163,696 sq mi (423,970 km2), California is among the most geographically diverse states. The Sierra Nevada, the fertile farmlands of the Central Valley, and the arid Mojave Desert of the south are some of the major geographic features of this U.S. state. It is home to some of the world's most exceptional trees: the tallest, most massive, and oldest. It is also home to both the highest and lowest points in the 48 contiguous states. The state is generally divided into Northern and Southern California, although the boundary between the two is not well defined. San Francisco is decidedly a Northern California city and Los Angeles likewise a Southern California one, but areas in between do not often share their confidence in geographic identity. The US Geological Survey defines the geographic center of California about 7.1 miles driving distance from the United States Forest Service office in the Northern Californian city of North Fork, California.

Southern California is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area as well as the Inland Empire. The region generally contains ten of California's 58 counties: Imperial, Kern, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura counties.

The Santa Ana winds are strong, extremely dry downslope winds that originate inland and affect coastal Southern California and northern Baja California. They originate from cool, dry high-pressure air masses in the Great Basin.

The Pacific Coast Ranges are the series of mountain ranges that stretch along the West Coast of North America from Alaska south to Northern and Central Mexico. Although they are commonly thought to be the westernmost mountain range of the continental United States and Canada, the geologically distinct Insular Mountains of Vancouver Island lie farther west.

The Transverse Ranges are a group of mountain ranges of southern California, in the Pacific Coast Ranges physiographic region in North America. The Transverse Ranges begin at the southern end of the California Coast Ranges and lie within Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside and Kern counties. The Peninsular Ranges lie to the south. The name Transverse Ranges is due to their east–west orientation, making them transverse to the general northwest–southeast orientation of most of California's coastal mountains.

The Peninsular Ranges are a group of mountain ranges that stretch 1,500 km (930 mi) from Southern California to the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula; they are part of the North American Pacific Coast Ranges, which run along the Pacific Coast from Alaska to Mexico. Elevations range from 150 to 3,300 m.

The Santa Clarita Valley (SCV) is part of the upper watershed of the Santa Clara River in Southern California. The valley was part of the 48,612-acre (19,673 ha) Rancho San Francisco Mexican land grant. Located in Los Angeles County, its main population center is the city of Santa Clarita which includes the neighborhoods of Canyon Country, Newhall, Saugus, and Valencia. Adjacent unincorporated communities include Castaic, Stevenson Ranch, Val Verde, and Valencia.

The Santa Ana River is the largest river entirely within Southern California in the United States. It rises in the San Bernardino Mountains and flows for most of its length through San Bernardino and Riverside counties, before cutting through the northern Santa Ana Mountains via Santa Ana Canyon and flowing southwest through urban Orange County to drain into the Pacific Ocean. The Santa Ana River is 96 miles (154 km) long, and its drainage basin is 2,650 square miles (6,900 km2) in size.

The San Bernardino Mountains are a high and rugged mountain range in Southern California in the United States. Situated north and northeast of San Bernardino and spanning two California counties, the range tops out at 11,503 feet (3,506 m) at San Gorgonio Mountain – the tallest peak in Southern California. The San Bernardinos form a significant region of wilderness and are popular for hiking and skiing.

The San Jacinto Mountains are a mountain range in Riverside County, located east of Los Angeles in southern California in the United States. The mountains are named for one of the first Black Friars, Saint Hyacinth, who is a popular patron in Latin America.

The San Bernardino Valley is a valley in Southern California located at the south base of the Transverse Ranges. It is bordered on the north by the eastern San Gabriel Mountains and the San Bernardino Mountains; on the east by the San Jacinto Mountains; on the south by the Temescal Mountains and Santa Ana Mountains; and on the west by the Pomona Valley. Elevation varies from 590 feet (180 m) on valley floors near Chino to 1,380 feet (420 m) near San Bernardino and Redlands. The valley floor is home to over 80% of the more than 4 million people in the Inland Empire region.

The Coast Ranges of California span 400 miles (644 km) from Del Norte or Humboldt County, California, south to Santa Barbara County. The other three coastal California mountain ranges are the Transverse Ranges, Peninsular Ranges and the Klamath Mountains.

The climate of California varies widely from hot desert to alpine tundra, depending on latitude, elevation, and proximity to the Pacific Coast. California's coastal regions, the Sierra Nevada foothills, and much of the Central Valley have a Mediterranean climate, with warmer, drier weather in summer and cooler, wetter weather in winter. The influence of the ocean generally moderates temperature extremes, creating warmer winters and substantially cooler summers in coastal areas.

The climate of San Diego, California is classified as a hot-summer Mediterranean climate. The basic climate features hot, sunny, and dry summers, and cooler, wetter winters. However, San Diego is much more arid than typical Mediterranean climates, and winters are still dry compared with most other zones with this type of climate. The climate at San Diego International Airport, the location for official weather reports for San Diego, as well as the climate at most beach areas, straddles the border between BSh and BSk due to the mild winters and cool summers in these locations.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the U.S. state of California.

The Santa Rosa Wilderness is a 72,259-acre (292.42 km2) wilderness area in Southern California, in the Santa Rosa Mountains of Riverside and San Diego counties, California. It is in the Colorado Desert section of the Sonoran Desert, above the Coachella Valley and Lower Colorado River Valley regions in a Peninsular Range, between La Quinta to the north and Anza Borrego Desert State Park to the south. The United States Congress established the wilderness in 1984 with the passage of the California Wilderness Act, managed by both the US Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In 2009, the Omnibus Public Land Management Act was signed into law which added more than 2,000 acres (8.1 km2). Most of the Santa Rosa Wilderness is within the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument.

The California montane chaparral and woodlands is an ecoregion defined by the World Wildlife Fund, spanning 7,900 square miles (20,000 km2) of mountains in the Transverse Ranges, Peninsular Ranges, and Coast Ranges of southern and central California. The ecoregion is part of the larger California chaparral and woodlands ecoregion, and belongs to the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub biome.

The geology of California is highly complex, with numerous mountain ranges, substantial faulting and tectonic activity, rich natural resources and a history of both ancient and comparatively recent intense geological activity. The area formed as a series of small island arcs, deep-ocean sediments and mafic oceanic crust accreted to the western edge of North America, producing a series of deep basins and high mountain ranges.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Peninsular Ranges rain shadow.