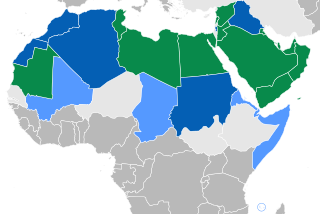

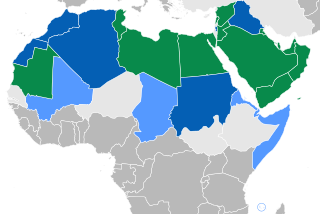

Arabic is a Central Semitic language of the Semitic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The ISO assigns language codes to 32 varieties of Arabic, including its standard form of Literary Arabic, known as Modern Standard Arabic, which is derived from Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

The Nabataeans or Nabateans were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu —gave the name Nabatene to the Arabian borderland that stretched from the Euphrates to the Red Sea.

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad and Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, elevated prose and oratory, and is also the liturgical language of Islam. Classical Arabic is, furthermore, the register of the Arabic language on which Modern Standard Arabic is based.

Dushara, also transliterated as Dusares, is a pre-Islamic Arabian god worshipped by the Nabataeans at Petra and Madain Saleh. Safaitic inscriptions imply he was the son of Al-Lat, and that he assembled in the heavens with other gods. He is called "Dushara from Petra" in one inscription. Dushara was expected to bring justice if called by the correct ritual.

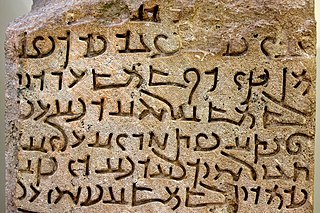

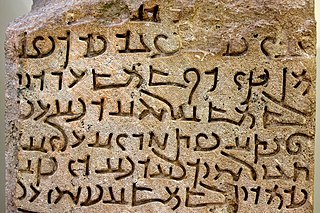

It is thought that the Arabic alphabet is a derivative of the Nabataean variation of the Aramaic alphabet, which descended from the Phoenician alphabet, which among others also gave rise to the Hebrew alphabet and the Greek alphabet, the latter one being in turn the base for the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets.

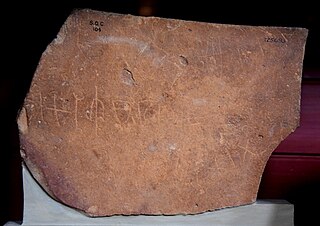

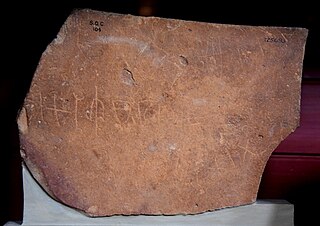

Safaitic is a variety of the South Semitic scripts used by the Arabs in southern Syria and northern Jordan in Ḥarrah region, to carve rock inscriptions in various dialects of Old Arabic and Ancient North Arabian. The Safaitic script is a member of the Ancient North Arabian (ANA) sub-grouping of the South Semitic script family, the genetic unity of which has yet to be demonstrated.

Ancient North Arabian (ANA) is a collection of scripts and a language or family of languages under the North Arabian languages branch along with Old Arabic that were used in north and central Arabia and south Syria from the 8th century BCE to the 4th century CE. The term "Ancient North Arabian" is defined negatively. It refers to all of the South Semitic scripts except Ancient South Arabian (ASA) regardless of their genetic relationships.

Nabataean Aramaic is the extinct Aramaic variety used in inscriptions by the Nabataeans of the East Bank of the Jordan River, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula. Compared with other varieties of Aramaic, it is notable for the occurrence of a number of loanwords and grammatical borrowings from Arabic or other North Arabian languages.

Old Aramaic refers to the earliest stage of the Aramaic language, known from the Aramaic inscriptions discovered since the 19th century.

Aramaic of Hatra, Hatran Aramaic or Ashurian designates a Middle Aramaic dialect, that was used in the region of Hatra and Assur in northeastern parts of Mesopotamia, approximately from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century CE. Its range extended from the Nineveh Plains in the centre, up to Tur Abdin in the north, Dura-Europos in the west and Tikrit in the south.

Hismaic is a variety of the Ancient North Arabian script and the language most commonly expressed in it. The Hismaic script may have been used to write Safaitic dialects of Old Arabic, but the language of most inscriptions differs from Safaitic in a few important respects, meriting its classification as a separate dialect or language. Hismaic inscriptions are attested in the Ḥismā region of Northwest Arabia, dating to the centuries around and immediately following the start of the Common Era.

Proto-Arabic is the name given to the hypothetical reconstructed ancestor of all the varieties of Arabic attested since the 9th century BC. There are two lines of evidence to reconstruct Proto-Arabic:

The South Semitic scripts are a family of alphabets that had split from Proto-Sinaitic script by the 10th century BC. The family has two main branches: Ancient North Arabian (ANA) and Ancient South Arabian (ASA). The scripts were exclusive to Arabia and the Horn of Africa. All the ANA and most of the ASA scripts fell out of use by the 6th century AD. The exception was Geʽez, a child of ASA in use in Ethiopia. It and its variants remain in use today for various Ethiosemitic languages. In Arabia, the South Semitic scripts were replaced by the Arabic script, which is descended from the Nabataean script.

Taymanitic was the language and script of the oasis of Taymāʾ in northwestern Arabia, dated to the second half of the 6th century BC.

Nabataean Arabic was the dialect of Arabic spoken by the Nabataeans in antiquity. It was succeeded by Paleo-Arabic.

Old Hijazi, is a variety of Old Arabic attested in Hejaz from about the 1st century to the 7th century. It is the variety thought to underlie the Quranic Consonantal Text (QCT) and in its later iteration was the prestige spoken and written register of Arabic in the Umayyad Caliphate.

David F. Graf, is an American historian, archeologist, academic and author. He is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Miami.

Paleo-Arabic is a script that represents a pre-Islamic phase in the evolution of the Arabic script at which point it becomes recognizably similar to the Islamic Arabic script. It comes prior to Classical Arabic, but it is also a recognizable form of the Arabic script, emerging after a transitional phase of Nabataean Arabic as the Nabataean script slowly evolved into the modern Arabic script. It appears in the late fifth and sixth centuries and, though was originally only known from Syria and Jordan, is now also attested in several extant inscriptions from the Arabian Peninsula, such as in the Christian texts at the site of Hima in South Arabia. More recently, additional examples of Paleo-Arabic have been discovered near Taif in the Hejaz and in the Tabuk region of northwestern Saudi Arabia.

The Yazīd inscription is an early Christian Paleo-Arabic rock carving from the region of as-Samrūnīyyāt, 12 km southeast of Qasr Burqu' in the northeastern Jordan.

The practice of polytheistic religion dominated in pre-Islamic Arabia until the fourth century. Inscriptions in various scripts used in the Arabian Peninsula including the Nabataean script, Safaitic, and Sabaic attest to the practice of polytheistic cults and idols until the fourth century, whereas material evidence from the fifth century onwards is almost categorically monotheistic. It is in this era that Christianity, Judaism, and other generic forms of monotheism become salient among Arab populations. In South Arabia, the ruling class of the Himyarite Kingdom would convert to Judaism and a cessation of polytheistic inscriptions is witnessed. Monotheistic religion would continue as power in this region transitioned to Christian rulers, principally Abraha, in the early sixth century.