Transport economics is a branch of economics founded in 1959 by American economist John R. Meyer that deals with the allocation of resources within the transport sector. It has strong links to civil engineering. Transport economics differs from some other branches of economics in that the assumption of a spaceless, instantaneous economy does not hold. People and goods flow over networks at certain speeds. Demands peak. Advance ticket purchase is often induced by lower fares. The networks themselves may or may not be competitive. A single trip may require the bundling of services provided by several firms, agencies and modes.

The London congestion charge is a fee charged on most cars and motor vehicles being driven within the Congestion Charge Zone (CCZ) in Central London between 7:00 am and 6:00 pm Monday to Friday, and between 12:00 noon and 6:00 pm Saturday and Sunday.

Congestion pricing or congestion charges is a system of surcharging users of public goods that are subject to congestion through excess demand, such as through higher peak charges for use of bus services, electricity, metros, railways, telephones, and road pricing to reduce traffic congestion; airlines and shipping companies may be charged higher fees for slots at airports and through canals at busy times. Advocates claim this pricing strategy regulates demand, making it possible to manage congestion without increasing supply.

Traffic congestion is a condition in transport that is characterized by slower speeds, longer trip times, and increased vehicular queueing. Traffic congestion on urban road networks has increased substantially since the 1950s, resulting in many of the roads becoming obsolete. When traffic demand is great enough that the interaction between vehicles slows the traffic stream, this results in congestion. While congestion is a possibility for any mode of transportation, this article will focus on automobile congestion on public roads.

The Singapore Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) was a road pricing scheme introduced in Singapore from 1975 to 1998 that charged drivers who were entering downtown Singapore. This was the first urban traffic congestion pricing scheme to be successfully implemented in the world. This scheme affected all roads entering a 6-square-kilometre area in the Central Business District (CBD) called the "Restricted Zone" (RZ), later increased to 7.25 square kilometres to include areas that later became commercial in nature. The scheme was later replaced in 1998 by the Electronic Road Pricing.

Electronic toll collection (ETC) is a wireless system to automatically collect the usage fee or toll charged to vehicles using toll roads, HOV lanes, toll bridges, and toll tunnels. It is a faster alternative which is replacing toll booths, where vehicles must stop and the driver manually pays the toll with cash or a card. In most systems, vehicles using the system are equipped with an automated radio transponder device. When the vehicle passes a roadside toll reader device, a radio signal from the reader triggers the transponder, which transmits back an identifying number which registers the vehicle's use of the road, and an electronic payment system charges the user the toll.

The Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) system is an electronic toll collection scheme adopted in Singapore to manage traffic by way of road pricing, and as a usage-based taxation mechanism to complement the purchase-based Certificate of Entitlement system. There are a total of 93 ERP gantries being built and located throughout the country, along expressways and roads leading towards the Central Area. As of July 2024, only 19 ERP gantries are in operation and are all in expressways where congestion continues to be severe.

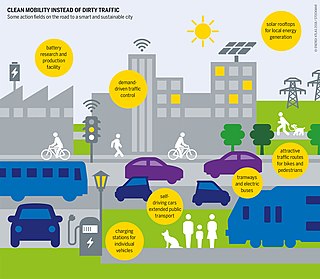

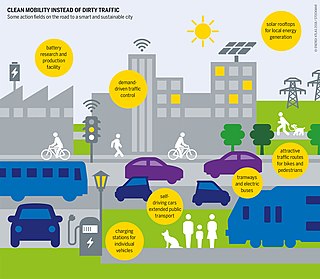

Sustainable transport refers to ways of transportation that are sustainable in terms of their social and environmental impacts. Components for evaluating sustainability include the particular vehicles used for road, water or air transport; the source of energy; and the infrastructure used to accommodate the transport. Transport operations and logistics as well as transit-oriented development are also involved in evaluation. Transportation sustainability is largely being measured by transportation system effectiveness and efficiency as well as the environmental and climate impacts of the system. Transport systems have significant impacts on the environment, accounting for between 20% and 25% of world energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. The majority of the emissions, almost 97%, came from direct burning of fossil fuels. In 2019, about 95% of the fuel came from fossil sources. The main source of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union is transportation. In 2019 it contributes to about 31% of global emissions and 24% of emissions in the EU. In addition, up to the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions have only increased in this one sector. Greenhouse gas emissions from transport are increasing at a faster rate than any other energy using sector. Road transport is also a major contributor to local air pollution and smog.

The Edinburgh congestion charge was a proposed scheme of congestion pricing for Scotland's capital city. It planned to reduce congestion by introducing a daily charge to enter a cordon within the inner city, with the money raised directed to fund improvements in public transport. The scheme was the subject of intense public and political debate and ultimately rejected. A referendum was held and nearly three-quarters of respondents rejected the proposals.

A low-emission zone (LEZ) is a defined area where access by some polluting vehicles is restricted or deterred with the aim of improving air quality. This may favour vehicles such as bicycles, micromobility vehicles, (certain) alternative fuel vehicles, hybrid electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids, and zero-emission vehicles such as all-electric vehicles.

Motoring taxation in the United Kingdom consists primarily of vehicle excise duty, which is levied on vehicles registered in the UK, and hydrocarbon oil duty, which is levied on the fuel used by motor vehicles. VED and fuel tax raised approximately £32 billion in 2009, a further £4 billion was raised from the value added tax on fuel purchases. Motoring-related taxes for fiscal year 2011/12, including fuel duties and VED, are estimated to amount to more than £38 billion, representing almost 7% of total UK taxation.

In New York City, a planned congestion pricing project would charge vehicles traveling into or within the central business district of Manhattan. This disincentivizing fee, intended to cut down on traffic congestion and pollution, was first proposed in 2007 and included in the 2019 New York state government budget by the New York State Legislature. As of June 2024, New York governor Kathy Hochul had indefinitely postponed the congestion charge. If the plan goes into effect, tolls will be collected electronically and will vary depending on the time of day, type of vehicle, and whether a vehicle has an E-ZPass toll transponder. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) estimates a profit of $15 billion should the plan be implemented, which it intends to invest into long-term transportation initiatives citywide.

The London Low Emission Zone (LEZ) is an area of London in which an emissions standard based charge is applied to non-compliant commercial vehicles. Its aim is to reduce the exhaust emissions of diesel-powered vehicles in London. This scheme should not be confused with the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), introduced in April 2019, which applies to all vehicles. Vehicles that do not conform to various emission standards are charged; the others may enter the controlled zone free of charge. The low emission zone started operating on 4 February 2008 with phased introduction of an increasingly stricter regime until 3 January 2012. The scheme is administered by the Transport for London executive agency within the Greater London Authority.

The Smeed Report was a study into alternative methods of charging for road use, commissioned by the UK government between 1962 and 1964 led by R. J. Smeed. The report stopped short of an unqualified recommendation for road pricing but supported congestion pricing for busy road networks.

Road space rationing, also known as alternate-day travel, driving restriction and no-drive days, is a travel demand management strategy aimed to reduce the negative externalities generated by urban air pollution or peak urban travel demand in excess of available supply or road capacity, through artificially restricting demand by rationing the scarce common good road capacity, especially during the peak periods or during peak pollution events. This objective is achieved by restricting traffic access into an urban cordon area, city center (CBD), or district based upon the last digits of the license number on pre-established days and during certain periods, usually, the peak hours.

The Ecopass program was a traffic pollution charge implemented in Milan, Italy, as an urban toll for some motorists traveling within a designated traffic restricted zone or ZTL, corresponding to the central Cerchia dei Bastioni area and encircling around 8.2 km2 (3.2 sq mi). The Ecopass was implemented as a one-year trial program on 2 January 2008, and later extended until 31 December 2009. A public consultation was planned to be conducted early in 2009 to decide if the charge becomes permanent. Subsequently, the charge-scheme was prolonged until 31 December 2011. Starting from 16 January 2012, a new scheme was introduced, converting it from a pollution-charge to a conventional congestion charge.

San Francisco congestion pricing is a proposed traffic congestion user fee for vehicles traveling into the most congested areas of the city of San Francisco at certain periods of peak demand. The charge would be combined with other traffic reduction projects. The proposed congestion pricing charge is part of a mobility and pricing study being carried out by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) to reduce congestion at and near central locations and to reduce its associated environmental impacts, including cutting greenhouse gas emissions. The funds raised through the charge will be used for public transit improvement projects, and for pedestrian and bike infrastructure and enhancements.

Area C is a congestion charge active in the city center of Milan, Italy. It was introduced in 2012, replacing the previous pollution charge Ecopass and based on the same designated traffic restricted zone. The area is about 8.2 km2 (3.2 sq mi) with 77,000 residents and is accessible through gates monitored by traffic cameras.

Road pricing in the United Kingdom used to be limited to conventional tolls in some bridges, tunnels and also for some major roads during the period of the Turnpike trusts. The term road pricing itself only came into common use however with publication of the Smeed Report in 1964 which considered how to implement congestion charging in urban areas as a transport demand management method to reduce traffic congestion.

The externalities of automobiles, similar to other economic externalities, represent the measurable costs imposed on those who do not own the vehicle, in contrast to the costs borne by the vehicle owner. These externalities include factors such as air pollution, noise, traffic congestion, and road maintenance costs, which affect the broader community and environment. Additionally, these externalities contribute to social injustice, as disadvantaged communities often bear a disproportionate share of these negative impacts. According to Harvard University, the main externalities of driving are local and global pollution, oil dependence, traffic congestion and traffic collisions; while according to a meta-study conducted by the Delft University these externalities are congestion and scarcity costs, accident costs, air pollution costs, noise costs, climate change costs, costs for nature and landscape, costs for water pollution, costs for soil pollution and costs of energy dependency.