A subtropical cyclone is a weather system that has some characteristics of both tropical and extratropical cyclones.

Tropical cyclones and subtropical cyclones are named by various warning centers to simplify communication between forecasters and the general public regarding forecasts, watches and warnings. The names are intended to reduce confusion in the event of concurrent storms in the same basin. Once storms develop sustained wind speeds of more than 33 knots, names are generally assigned to them from predetermined lists, depending on the basin in which they originate. Some tropical depressions are named in the Western Pacific, while tropical cyclones must contain a significant amount of gale-force winds before they are named in the Southern Hemisphere.

The 1997 Atlantic hurricane season was a below-average hurricane season. It officially began on June 1, and lasted until November 30 of that year. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The 1997 season was fairly inactive, with only seven named storms forming, with an additional tropical depression and an unnumbered subtropical storm. It was the first time since the 1961 season that there were no active tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin during the entire month of August–historically one of the more active months of the season—a phenomenon that would not occur again until 2022. A strong El Niño is credited with reducing activity in the Atlantic, while increasing the number of storms in the eastern and western Pacific basins to 19 and 26 storms, respectively. As is common in El Niño years, tropical cyclogenesis was suppressed in the tropical latitudes, with only two becoming tropical storms south of 25°N.

The 1965 Atlantic hurricane season was the first to use the modern-day bounds for an Atlantic hurricane season, which are June 1 to November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. It was a slightly below average season, with 10 tropical cyclones developing and reaching tropical storm intensity. Four of the storms strengthened into hurricanes. One system reached major hurricane intensity – Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale. The first system, an unnamed tropical storm, developed during the month of June in the southern Gulf of Mexico. The storm moved northward across Central America, but caused no known impact in the region. It struck the Florida Panhandle and caused minor impact across much of the Southern United States. Tropical cyclogenesis halted for over two months, until Anna formed on August 21. The storm remained well away from land in the far North Atlantic Ocean and caused no impact.

The 1969 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season since the 1933 season, and was the final year of the most recent positive Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO) era. The hurricane season officially began on June 1, and lasted until November 30. Altogether, 12 tropical cyclones reached hurricane strength, the highest number on record at the time; a mark not surpassed until 2005. The season was above-average despite an El Niño, which typically suppresses activity in the Atlantic Ocean, while increasing tropical cyclone activity in the Pacific Ocean. Activity began with a tropical depression that caused extensive flooding in Cuba and Jamaica in early June. On July 25, Tropical Storm Anna developed, the first named storm of the season. Later in the season, Tropical Depression Twenty-Nine caused severe local flooding in the Florida Panhandle and southwestern Georgia in September.

The 1974 Atlantic hurricane season was a destructive and deadly hurricane season. In terms of overall activity, it was near average, with eleven named storms forming, of which four became hurricanes. Two of those four became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher systems on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean.

The 1975 Atlantic hurricane season was a near average hurricane season with nine named storms forming, of which six became hurricanes. Three of those six became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher systems on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean.

The 1976 Atlantic hurricane season was a fairly average Atlantic hurricane season in which 21 tropical or subtropical cyclones formed. 10 of them became nameable storms. Six of those reached hurricane strength, with two of the six became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the first system, a subtropical storm, developed in the Gulf of Mexico on May 21, several days before the official start of the season. The system spawned nine tornadoes in Florida, resulting in about $628,000 (1976 USD) in damage, though impact was minor otherwise.

The 1944 Atlantic hurricane season featured the first instance of upper-tropospheric observations from radiosonde – a telemetry device used to record weather data in the atmosphere – being incorporated into tropical cyclone track forecasting for a fully developed hurricane. The season officially began on June 15, 1944, and ended on November 15, 1944. These dates describe the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The season's first cyclone developed on July 13, while the final system became an extratropical cyclone by November 13. The season was fairly active season, with 14 tropical storms, 8 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. In real-time, forecasters at the Weather Bureau tracked eleven tropical storms, but later analysis uncovered evidence of three previously unclassified tropical storms.

The 1925 Atlantic hurricane season was a below-average Atlantic hurricane season during which four tropical cyclones formed. Only one of them was a hurricane. The first storm developed on August 18, and the last dissipated on December 1. The season began at a late date, more than two months after the season began. The official start of the season is generally considered to be June 1 with the end being October 31; however, the final storm of the season formed nearly a month after the official end. Due to increased activity over the following decades, the official end of the hurricane season was shifted to November 30.

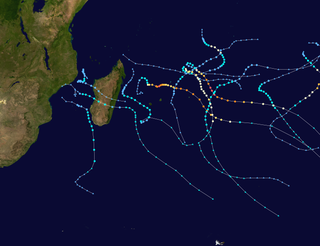

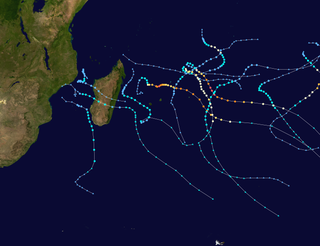

The 2014–15 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season was an above average event in tropical cyclone formation. It began on November 15, 2014, and ended on April 30, 2015, with the exception for Mauritius and the Seychelles, for which it ended on May 15, 2015. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical and subtropical cyclones form in the basin, which is west of 90°E and south of the Equator. Tropical and subtropical cyclones in this basin are monitored by the Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre in Réunion.

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season was the third in a consecutive series of above-average and damaging Atlantic hurricane seasons, featuring 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, which caused a total of over $50 billion in damages and at least 172 deaths. More than 98% of the total damage was caused by two hurricanes. The season officially began on June 1, 2018, and ended on November 30, 2018. These dates historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Alberto on May 25, making this the fourth consecutive year in which a storm developed before the official start of the season. The season concluded with Oscar transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on October 31, almost a month before the official end.

The 2019 Atlantic hurricane season was the fourth consecutive above-average and damaging season dating back to 2016. The season featured eighteen named storms, however, many storms were weak and short-lived, especially towards the end of the season. Six of those named storms achieved hurricane status, while three intensified into major hurricanes. Two storms became Category 5 hurricanes, marking the fourth consecutive season with at least one Category 5 hurricane, the third consecutive season to feature at least one storm making landfall at Category 5 intensity, and the seventh on record to have multiple tropical cyclones reaching Category 5 strength. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Subtropical Storm Andrea on May 20, making this the fifth consecutive year in which a tropical or subtropical cyclone developed outside of the official season.

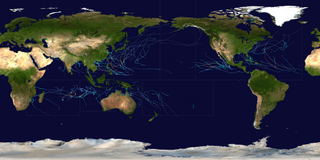

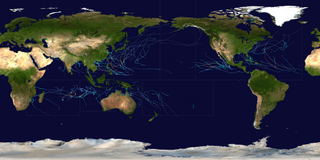

During 2015, tropical cyclones formed in seven major bodies of water, commonly known as tropical cyclone basins. Tropical cyclones will be assigned names by various weather agencies if they attain maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. During the year, one hundred thirty-four systems have formed and ninety-two were named. The most intense storm of the year was Hurricane Patricia, with maximum 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 345 km/h (215 mph) and a minimum pressure of 872 hPa (25.75 inHg). The deadliest tropical cyclone was Cyclone Komen, which caused 280 fatalities in Southeast India and Bangladesh, while the costliest was Typhoon Mujigae, which caused an estimated $4.25 billion USD in damage after striking China. Forty Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including nine Category 5 tropical cyclones in the year. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2015, as calculated by Colorado State University (CSU) was 1047 units.

During 2016, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, 140 tropical cyclones formed in bodies of water known as tropical cyclone basins. Of these, 84, including two subtropical cyclones in the South Atlantic Ocean and two tropical-like cyclones in the Mediterranean, were named by various weather agencies when they attained maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. The strongest storm of the year was Winston, peaking with a pressure of 884 hPa (26.10 inHg) and with 10-minute sustained winds of 285 km/h (175 mph) before striking Fiji. The costliest and deadliest tropical cyclone in 2016 was Hurricane Matthew, which impacted Haiti, Cuba, Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas, causing US$15.09 billion in damage. Matthew killed 603 people; 546 in Haiti, 47 in United States, 4 in Cuba and Dominican Republic, and 1 in Colombia and St. Vincent.

Subtropical Storm Alpha was the first subtropical or tropical cyclone ever observed to make landfall in mainland Portugal. The twenty-second tropical or subtropical cyclone and twenty-first named storm of the extremely active and record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Alpha originated from a large non-tropical low that was first monitored by the National Hurricane Center on 15 September. Initially not anticipated to transition into a tropical cyclone, the low gradually tracked south-southeastward for several days with little development. By early on 17 September, the low had separated from its frontal features and exhibited sufficient organization to be classified as a subtropical cyclone, as it approached the Iberian Peninsula, becoming a subtropical storm around that time. Alpha then made landfall just south of Figueira da Foz, Portugal during the evening of 18 September, then rapidly weakened as it moved over the mountainous terrain of Northeastern Portugal. The system degenerated into a remnant low on 19 September, when it was last noted.

During 2021, tropical cyclones formed in seven major bodies of water, commonly known as tropical cyclone basins. Tropical cyclones will be assigned names by various weather agencies if they attain maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. During the year, one hundred forty-five systems have formed and ninety-one were named, including one subtropical depression and excluding one system, which was unofficial. One storm was given two names by the same RSMC. The most intense storm of the year was Typhoon Surigae, with maximum 10-minute sustained wind speeds of 220 km/h (140 mph) and a minimum pressure of 895 hPa (26.43 inHg). The deadliest tropical cyclone was Typhoon Rai, which caused 410 fatalities in the Philippines and 1 in Vietnam, while the costliest was Hurricane Ida, which caused an estimated $75.25 billion USD in damage after striking Louisiana and the Northeastern United States.

Hurricane Pablo was a late-season Category 1 hurricane that became the farthest east-forming hurricane in the North Atlantic tropical cyclone basin on record, beating the previous record set by Hurricane Vince in 2005. The seventeenth tropical/subtropical cyclone, sixteenth named storm and sixth hurricane of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, Pablo originated from a baroclinic cyclone a few hundred miles west of the Azores Islands. The precursor cyclone formed on October 22, traveling eastward towards the island chain. The system initially had multiple centers of circulation, but they consolidated into one small low-pressure system embedded within the larger extratropical storm. On October 25, the embedded cyclone developed into a subtropical cyclone, receiving the name Pablo. The cyclone continued eastwards, transitioning into a fully-tropical storm later that day. Pablo quickly intensified between October 26 and 27, forming an eye and spiral rainbands. At 12:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) on October 27, Pablo intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. The storm continued to strengthen, reaching its peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg) at 18:00 UTC on the same day. The storm quickly weakened the next day, becoming extratropical again, and dissipated on October 29.

Subtropical Storm Ubá was the fourth tropical or subtropical cyclone to form in the South Atlantic Ocean in 2021. Ubá originated from an area of low pressure that formed off the coast of Rio de Janeiro and evolved into a subtropical cyclone on 10 December. The cyclone lingered for two days, before weakening back to a low-pressure area and dissipating on 13 December. Together with the South Atlantic Convergence Zone (SACZ), Ubá caused heavy rains in Minas Gerais, in Espírito Santo and mainly in Bahia. The storm became the deadliest South Atlantic (sub)tropical cyclone, with a death toll of 15.