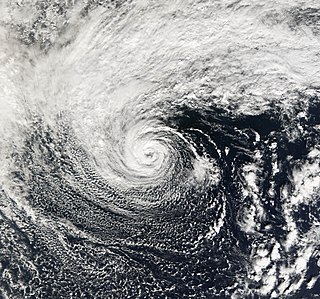

In meteorology, a cyclone is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above. Cyclones are characterized by inward-spiraling winds that rotate about a zone of low pressure. The largest low-pressure systems are polar vortices and extratropical cyclones of the largest scale. Warm-core cyclones such as tropical cyclones and subtropical cyclones also lie within the synoptic scale. Mesocyclones, tornadoes, and dust devils lie within the smaller mesoscale.

In meteorology, a low-pressure area, low area or low is a region where the atmospheric pressure is lower than that of surrounding locations. Low-pressure areas are commonly associated with inclement weather, while high-pressure areas are associated with lighter winds and clear skies. Winds circle anti-clockwise around lows in the northern hemisphere, and clockwise in the southern hemisphere, due to opposing Coriolis forces. Low-pressure systems form under areas of wind divergence that occur in the upper levels of the atmosphere (aloft). The formation process of a low-pressure area is known as cyclogenesis. In meteorology, atmospheric divergence aloft occurs in two kinds of places:

The 2000 Atlantic hurricane season was a fairly active hurricane season, but featured the latest first named storm in a hurricane season since 1992. The hurricane season officially began on June 1, and ended on November 30. It was slightly above average due to a La Niña weather pattern although most of the storms were weak. It was also the only season to have two of the storms affect Ireland. The first cyclone, Tropical Depression One, developed in the southern Gulf of Mexico on June 7 and dissipated after an uneventful duration. However, it would be almost two months before the first named storm, Alberto, formed near Cape Verde; Alberto also dissipated with no effects on land. Several other tropical cyclones—Tropical Depression Two, Tropical Depression Four, Chris, Ernesto, Nadine, and an unnamed subtropical storm—did not impact land. Five additional storms—Tropical Depression Nine, Florence, Isaac, Joyce, and Leslie—minimally affected land areas.

The 1967 Atlantic hurricane season was an active Atlantic hurricane season overall, producing 13 nameable storms, of which 6 strengthened into hurricanes. The season officially began on June 1, 1967, and lasted until November 30, 1967. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic Ocean. The season's first system, Tropical Depression One, formed on June 10, and the last, Tropical Storm Heidi, lost tropical characteristics on November 2.

The 1992 Atlantic hurricane season was a significantly below average season for overall tropical or subtropical cyclones as only ten formed. Six of them became named tropical storms, and four of those became hurricanes; one hurricane became a major hurricane. The season was also near-average in terms of accumulated cyclone energy. The season officially started on June 1 and officially ended on November 30. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by formation in April of an unnamed subtropical storm in the central Atlantic.

The 1970 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The season was fairly average, with 14 named storms forming, of which seven were hurricanes. Two of those seven became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. Also, this was the first season in which reconnaissance aircraft flew into all four quadrants of a tropical cyclone.

The 1974 Atlantic hurricane season was a destructive and deadly hurricane season. In terms of overall activity, it was near average, with eleven named storms forming, of which four became hurricanes. Two of those four became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher systems on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean.

The 1976 Atlantic hurricane season was an fairly average Atlantic hurricane season in which 21 tropical or subtropical cyclones formed. 10 of them became nameable storms. Six of those reached hurricane strength, with two of the six became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the first system, a subtropical storm, developed in the Gulf of Mexico on May 21, several days before the official start of the season. The system spawned nine tornadoes in Florida, resulting in about $628,000 (1976 USD) in damage, though impact was minor otherwise.

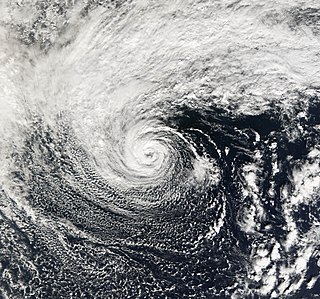

Hurricane Vince was an unusual hurricane that developed in the northeastern Atlantic basin. Forming in October during the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, it strengthened over waters thought to be too cold for tropical development. Vince was the twentieth named tropical cyclone and twelfth hurricane of the extremely active season.

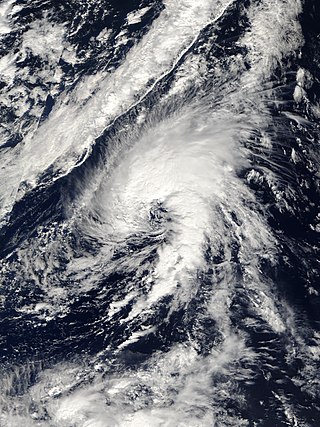

Tropical Storm Nicholas was a long-lived tropical storm in October and November of the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season. Forming from a tropical wave on October 13 in the central tropical Atlantic Ocean, Nicholas developed slowly due to moderate levels of wind shear throughout its lifetime. Deep convection slowly organized, and Nicholas attained a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) on October 17. After moving west-northwestward for much of its lifetime, it turned northward and weakened due to increasing shear. The storm again turned to the west and briefly restrengthened, but after turning again to the north Nicholas transitioned to an extratropical cyclone on October 24. As an extratropical storm, Nicholas executed a large loop to the west, and after moving erratically for a week and organizing into a tropical low, it was absorbed by a non-tropical low. The low continued westward, crossed Florida, and ultimately dissipated over the Gulf Coast of the United States on November 5.

Tropical cyclogenesis is the development and strengthening of a tropical cyclone in the atmosphere. The mechanisms through which tropical cyclogenesis occurs are distinctly different from those through which temperate cyclogenesis occurs. Tropical cyclogenesis involves the development of a warm-core cyclone, due to significant convection in a favorable atmospheric environment.

The 2005 Azores subtropical storm was the 19th nameable storm and only subtropical storm of the extremely active 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. It was not named by the National Hurricane Center as it was operationally classified as an extratropical low. It developed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, an unusual region for late-season tropical cyclogenesis. Nonetheless, the system was able to generate a well-defined centre convecting around a warm core on 4 October. The system was short-lived, crossing over the Azores later on 4 October before becoming extratropical again on 5 October. No damages or fatalities were reported during that time. Its remnants were soon absorbed into a cold front. That system went on to become Hurricane Vince, which affected the Iberian Peninsula.

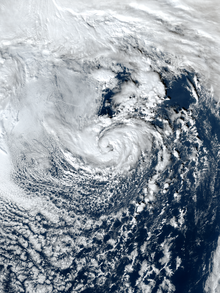

Extratropical cyclones, sometimes called mid-latitude cyclones or wave cyclones, are low-pressure areas which, along with the anticyclones of high-pressure areas, drive the weather over much of the Earth. Extratropical cyclones are capable of producing anything from cloudiness and mild showers to severe gales, thunderstorms, blizzards, and tornadoes. These types of cyclones are defined as large scale (synoptic) low pressure weather systems that occur in the middle latitudes of the Earth. In contrast with tropical cyclones, extratropical cyclones produce rapid changes in temperature and dew point along broad lines, called weather fronts, about the center of the cyclone.

The 2006 Central Pacific cyclone, also known as Invest 91C or Storm 91C, was an unusual weather system that formed in 2006. Forming on October 30 from a mid-latitude cyclone in the north Pacific mid-latitudes, it moved over waters warmer than normal. The system acquired some features more typical of subtropical and even tropical cyclones. However, as it neared the western coastline of North America, the system fell apart, dissipating soon after landfall, on November 4. Moisture from the storm's remnants caused substantial rainfall in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. The exact status and nature of this weather event is unknown, with meteorologists and weather agencies having differing opinions.

A cold-core low, also known as an upper level low or cold-core cyclone, is a cyclone aloft which has an associated cold pool of air residing at high altitude within the Earth's troposphere, without a frontal structure. It is a low pressure system that strengthens with height in accordance with the thermal wind relationship. If a weak surface circulation forms in response to such a feature at subtropical latitudes of the eastern north Pacific or north Indian oceans, it is called a subtropical cyclone. Cloud cover and rainfall mainly occurs with these systems during the day.

The following is a glossary of tropical cyclone terms.

Subtropical Cyclone Katie, unofficially named by researchers, was an unusual weather event in early 2015. After the 2014–15 South Pacific cyclone season had officially ended, a rare subtropical cyclone was identified outside of the basin near Easter Island, during early May, and was unofficially dubbed Katie by researchers. Katie was one of the few tropical or subtropical systems ever observed forming in the far Southeast Pacific, outside of the official basin boundary of 120°W, which marks the eastern edge of RSMC Nadi's and RSMC Wellington's warning areas, during the satellite era. Due to the fact that this storm developed outside of the official areas of responsibility of the warning agencies in the South Pacific, the storm was not officially included as a part of the 2014–15 South Pacific cyclone season. However, the Chilean Navy Weather Service issued High Seas Warnings on the system as an extratropical low.

Hurricane Alex was the first Atlantic hurricane to occur in January since Hurricane Alice of 1954–55. Alex originated as a non-tropical low near the Bahamas on January 7, 2016. Initially traveling northeast, the system passed by Bermuda on January 8 before turning southeast and deepening. It briefly acquired hurricane-force winds by January 10, then weakened slightly before curving towards the east and later northeast. Acquiring more tropical weather characteristics over time, the system transitioned into a subtropical cyclone well south of the Azores on January 12, becoming the first North Atlantic tropical or subtropical cyclone in January since Tropical Storm Zeta of 2005–2006. Alex continued to develop tropical features while turning north-northeast, and transitioned into a fully tropical cyclone on January 14. The cyclone peaked in strength as a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale (SSHWS), with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph and a central pressure of 981 mbar. Alex weakened to a high-end tropical storm before making landfall on Terceira Island on January 15. By that time, the storm was losing its tropical characteristics; it fully transitioned back into a non-tropical cyclone several hours after moving away from the Azores. Alex ultimately merged with another cyclone over the Labrador Sea on January 17.

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season was the third-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of number of tropical cyclones, although many of them were weak and short-lived. With 21 named storms forming, it became the second season in a row and third overall in which the designated 21-name list of storm names was exhausted. Seven of those storms strengthened into a hurricane, four of which reached major hurricane intensity, which is slightly above-average. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period in each year when most Atlantic tropical cyclones form. However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the development of Tropical Storm Ana on May 22, making this the seventh consecutive year in which a storm developed outside of the official season.

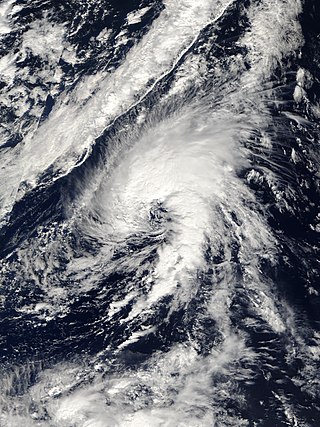

Subtropical Storm Alpha was the first subtropical or tropical cyclone ever observed to make landfall in mainland Portugal. The twenty-second tropical or subtropical cyclone and twenty-first named storm of the extremely active and record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Alpha originated from a large non-tropical low that was first monitored by the National Hurricane Center on 15 September. Initially not anticipated to transition into a tropical cyclone, the low gradually tracked south-southeastward for several days with little development. By early on 17 September, the low had separated from its frontal features and exhibited sufficient organization to be classified as a subtropical cyclone, as it approached the Iberian Peninsula, becoming a subtropical storm around that time. Alpha then made landfall just south of Figueira da Foz, Portugal during the evening of 18 September, then rapidly weakened as it moved over the mountainous terrain of Northeastern Portugal. The system degenerated into a remnant low on 19 September, when it was last noted.