Ecology is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps with the closely related sciences of biogeography, evolutionary biology, genetics, ethology, and natural history.

An invasive species is an introduced species to an environment that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native species that become harmful to their native environment after human alterations to its food web. Since the 20th century, invasive species have become a serious economic, social, and environmental threat worldwide.

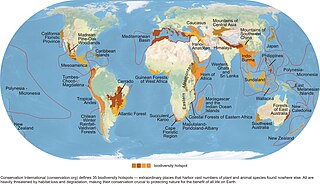

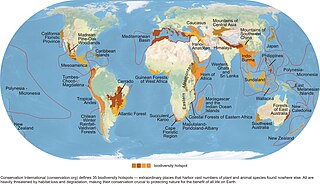

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an interdisciplinary subject drawing on natural and social sciences, and the practice of natural resource management.

Urban ecology is the scientific study of the relation of living organisms with each other and their surroundings in an urban environment. An urban environment refers to environments dominated by high-density residential and commercial buildings, paved surfaces, and other urban-related factors that create a unique landscape. The goal of urban ecology is to achieve a balance between human culture and the natural environment.

Habitat conservation is a management practice that seeks to conserve, protect and restore habitats and prevent species extinction, fragmentation or reduction in range. It is a priority of many groups that cannot be easily characterized in terms of any one ideology.

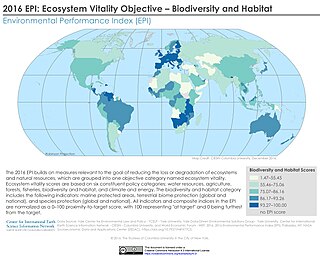

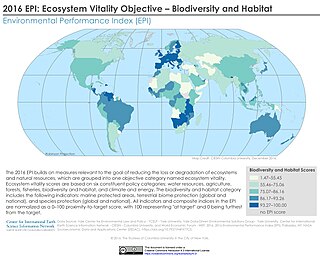

Ecosystem diversity deals with the variations in ecosystems within a geographical location and its overall impact on human existence and the environment.

Habitat destruction occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved to elsewhere or are dead, leading to a decrease in biodiversity and species numbers. Habitat destruction is in fact the leading cause of biodiversity loss and species extinction worldwide.

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution during history. The term is equivalent to the concept of indigenous or autochthonous species. A wild organism is known as an introduced species within the regions where it was anthropogenically introduced. If an introduced species causes substantial ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage, it may be regarded more specifically as an invasive species.

Brackish marshes develop from salt marshes where a significant freshwater influx dilutes the seawater to brackish levels of salinity. This commonly happens upstream from salt marshes by estuaries of coastal rivers or near the mouths of coastal rivers with heavy freshwater discharges in the conditions of low tidal ranges.

Wetland conservation is aimed at protecting and preserving areas of land including marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens that are covered by water seasonally or permanently due to a variety of threats from both natural and anthropogenic hazards. Some examples of these hazards include habitat loss, pollution, and invasive species. Wetland vary widely in their salinity levels, climate zones, and surrounding geography and play a crucial role in maintaining biodiversity, ecosystem services, and support human communities. Wetlands cover at least six percent of the Earth and have become a focal issue for conservation due to the ecosystem services they provide. More than three billion people, around half the world's population, obtain their basic water needs from inland freshwater wetlands. They provide essential habitats for fish and various wildlife species, playing a vital role in purifying polluted waters and mitigating the damaging effects of floods and storms. Furthermore, they offer a diverse range of recreational activities, including fishing, hunting, photography, and wildlife observation.

Assisted natural regeneration (ANR) is the human protection and preservation of natural tree seedlings in forested areas. Seedlings are, in particular, protected from undergrowth and extremely flammable plants such as Imperata grass. Though there is no formal definition or methodology, the overall goal of ANR is to create and improve forest productivity. It typically involves the reduction or removal of barriers to natural regeneration such as soil degradation, competition with weeds, grasses or other vegetation, and protection against disturbances, which can all interfere with growth. In addition to protection efforts, new trees are planted when needed or wanted. With ANR, forests grow faster than they would naturally, resulting in a significant contribution to carbon sequestration efforts. It also serves as a cheaper alternative to reforestation due to decreased nursery needs.

In ecology, a priority effect refers to the impact that a particular species can have on community development as a result of its prior arrival at a site. There are two basic types of priority effects: inhibitory and facilitative. An inhibitory priority effect occurs when a species that arrives first at a site negatively affects a species that arrives later by reducing the availability of space or resources. In contrast, a facilitative priority effect occurs when a species that arrives first at a site alters abiotic or biotic conditions in ways that positively affect a species that arrives later. Inhibitory priority effects have been documented more frequently than facilitative priority effects. Studies indicate that both abiotic and biotic factors can affect the strength of priority effects. Priority effects are a central and pervasive element of ecological community development that have significant implications for natural systems and ecological restoration efforts.

Riparian-zone restoration is the ecological restoration of riparian-zonehabitats of streams, rivers, springs, lakes, floodplains, and other hydrologic ecologies. A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. Riparian is also the proper nomenclature for one of the fifteen terrestrial biomes of the earth; the habitats of plant and animal communities along the margins and river banks are called riparian vegetation, characterized by aquatic plants and animals that favor them. Riparian zones are significant in ecology, environmental management, and civil engineering because of their role in soil conservation, their habitat biodiversity, and the influence they have on fauna and aquatic ecosystems, including grassland, woodland, wetland or sub-surface features such as water tables. In some regions the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, or riparian strip are used to characterize a riparian zone.

Forest restoration is defined as “actions to re-instate ecological processes, which accelerate recovery of forest structure, ecological functioning and biodiversity levels towards those typical of climax forest” i.e. the end-stage of natural forest succession. Climax forests are relatively stable ecosystems that have developed the maximum biomass, structural complexity and species diversity that are possible within the limits imposed by climate and soil and without continued disturbance from humans. Climax forest is therefore the target ecosystem, which defines the ultimate aim of forest restoration. Since climate is a major factor that determines climax forest composition, global climate change may result in changing restoration aims. Additionally, the potential impacts of climate change on restoration goals must be taken into account, as changes in temperature and precipitation patterns may alter the composition and distribution of climax forests.

The restoration economy is the economic activity associated with regenerative land use, such as ecological restoration activities. It stands in contrast to economic activity premised on sprawl, or on the extraction or depletion of natural resources. The term is meant to convey that activities meant to repair past damage to natural and human communities are often economically beneficial at local, regional, and national scales.

The term oyster reef refers to dense aggregations of oysters that form large colonial communities. Because oyster larvae need to settle on hard substrates, new oyster reefs may form on stone or other hard marine debris. Eventually the oyster reef will propagate by spat settling on the shells of older or nonliving oysters. The dense aggregations of oysters are often referred to as an oyster reef, oyster bed, oyster bank, oyster bottom, or oyster bar interchangeably. These terms are not well defined and often regionally restricted.

Woody plant encroachment is a natural phenomenon characterised by the increase in density of woody plants, bushes and shrubs, at the expense of the herbaceous layer, grasses and forbs. It predominantly occurs in grasslands, savannas and woodlands and can cause biome shifts from open grasslands and savannas to closed woodlands. The term bush encroachment refers to the expansion of native plants and not the spread of alien invasive species. It is thus defined by plant density, not species. Bush encroachment is often considered an ecological regime shift and can be a symptom of land degradation. The phenomenon is observed across different ecosystems and with different characteristics and intensities globally.

Bradley Cardinale is an American ecologist, conservation biologist, academic and researcher. He is Head of the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management and Penn State University.

Ashley H. Moerke is an American ecologist and a professor at Lake Superior State University. Her research focuses on freshwater ecosystem management, especially around the Great Lakes. Moerke advises local and state governments and bi-national commissions on water science, fisheries, and other environmental issues. In 2020, she was chosen as president-elect of the Society for Freshwater Science.