The pleural cavity, pleural space, or interpleural space is the potential space between the pleurae of the pleural sac that surrounds each lung. A small amount of serous pleural fluid is maintained in the pleural cavity to enable lubrication between the membranes, and also to create a pressure gradient.

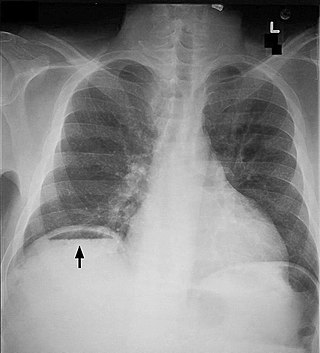

A hiatal hernia or hiatus hernia is a type of hernia in which abdominal organs slip through the diaphragm into the middle compartment of the chest. This may result in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) with symptoms such as a taste of acid in the back of the mouth or heartburn. Other symptoms may include trouble swallowing and chest pains. Complications may include iron deficiency anemia, volvulus, or bowel obstruction.

Aortic dissection (AD) occurs when an injury to the innermost layer of the aorta allows blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall, forcing the layers apart. In most cases, this is associated with a sudden onset of severe chest or back pain, often described as "tearing" in character. Vomiting, sweating, and lightheadedness may also occur. Damage to other organs may result from the decreased blood supply, such as stroke, lower extremity ischemia, or mesenteric ischemia. Aortic dissection can quickly lead to death from insufficient blood flow to the heart or complete rupture of the aorta.

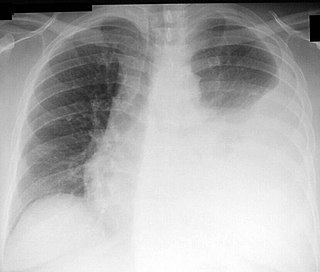

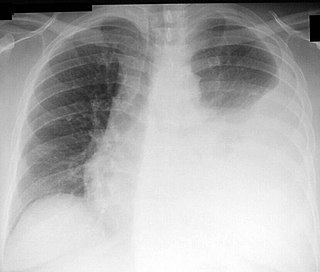

A pleural effusion is accumulation of excessive fluid in the pleural space, the potential space that surrounds each lung. Under normal conditions, pleural fluid is secreted by the parietal pleural capillaries at a rate of 0.6 millilitre per kilogram weight per hour, and is cleared by lymphatic absorption leaving behind only 5–15 millilitres of fluid, which helps to maintain a functional vacuum between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Excess fluid within the pleural space can impair inspiration by upsetting the functional vacuum and hydrostatically increasing the resistance against lung expansion, resulting in a fully or partially collapsed lung.

Mallory–Weiss syndrome or gastro-esophageal laceration syndrome refers to bleeding from a laceration in the mucosa at the junction of the stomach and esophagus. This is usually caused by severe vomiting because of alcoholism or bulimia, but can be caused by any condition which causes violent vomiting and retching such as food poisoning. The syndrome presents with hematemesis. The laceration is sometimes referred to as a Mallory–Weiss tear.

The mediastinum is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is an undelineated region that contains a group of structures within the thorax, namely the heart and its vessels, the esophagus, the trachea, the phrenic and cardiac nerves, the thoracic duct, the thymus and the lymph nodes of the central chest.

A hemothorax is an accumulation of blood within the pleural cavity. The symptoms of a hemothorax may include chest pain and difficulty breathing, while the clinical signs may include reduced breath sounds on the affected side and a rapid heart rate. Hemothoraces are usually caused by an injury, but they may occur spontaneously due to cancer invading the pleural cavity, as a result of a blood clotting disorder, as an unusual manifestation of endometriosis, in response to Pneumothorax, or rarely in association with other conditions.

A chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation of chyle, a type of lipid-rich lymph, in the space surrounding the lung. The lymphatics of the digestive system normally returns lipids absorbed from the small bowel via the thoracic duct, which ascends behind the esophagus to drain into the left brachiocephalic vein. If normal thoracic duct drainage is disrupted, either due to obstruction or rupture, chyle can leak and accumulate within the negative-pressured pleural space. In people on a normal diet, this fluid collection can sometimes be identified by its turbid, milky white appearance, since chyle contains emulsified triglycerides.

Thoracentesis, also known as thoracocentesis, pleural tap, needle thoracostomy, or needle decompression, is an invasive medical procedure to remove fluid or air from the pleural space for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. A cannula, or hollow needle, is carefully introduced into the thorax, generally after administration of local anesthesia. The procedure was first performed by Morrill Wyman in 1850 and then described by Henry Ingersoll Bowditch in 1852.

A pancreatic fistula is an abnormal communication between the pancreas and other organs due to leakage of pancreatic secretions from damaged pancreatic ducts. An external pancreatic fistula is one that communicates with the skin, and is also known as a pancreaticocutaneous fistula, whereas an internal pancreatic fistula communicates with other internal organs or spaces. Pancreatic fistulas can be caused by pancreatic disease, trauma, or surgery.

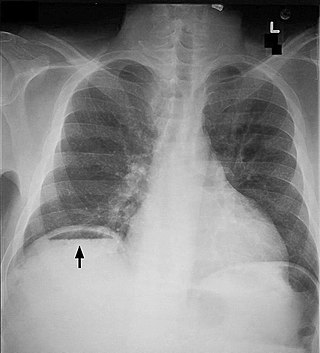

Pneumoperitoneum is pneumatosis in the peritoneal cavity, a potential space within the abdominal cavity. The most common cause is a perforated abdominal organ, generally from a perforated peptic ulcer, although any part of the bowel may perforate from a benign ulcer, tumor or abdominal trauma. A perforated appendix seldom causes a pneumoperitoneum.

Mediastinitis is inflammation of the tissues in the mid-chest, or mediastinum. It can be either acute or chronic. It is thought to be due to four different etiologies:

Pneumomediastinum is pneumatosis in the mediastinum, the central part of the chest cavity. First described in 1819 by René Laennec, the condition can result from physical trauma or other situations that lead to air escaping from the lungs, airways, or bowel into the chest cavity. In underwater divers it is usually the result of pulmonary barotrauma.

Hamman's syndrome, also known as Macklin's syndrome, is a syndrome of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum, sometimes associated with pain and, less commonly, dyspnea, dysphonia, and a low-grade fever.

A mediastinal tumor is a tumor in the mediastinum, the cavity that separates the lungs from the rest of the chest. It contains the heart, esophagus, trachea, thymus, and aorta. The most common mediastinal masses are neurogenic tumors, usually found in the posterior mediastinum, followed by thymoma (15–20%) located in the anterior mediastinum. Lung cancer typically spreads to the lymph nodes in the mediastinum.

Subcutaneous emphysema occurs when gas or air accumulates and seeps under the skin, where normally no gas should be present. Subcutaneous refers to the subcutaneous tissue, and emphysema refers to trapped air pockets. Since the air generally comes from the chest cavity, subcutaneous emphysema usually occurs around the upper torso, such as on the chest, neck, face, axillae and arms, where it is able to travel with little resistance along the loose connective tissue within the superficial fascia. Subcutaneous emphysema has a characteristic crackling-feel to the touch, a sensation that has been described as similar to touching warm Rice Krispies. This sensation of air under the skin is known as subcutaneous crepitation, a form of crepitus.

Pleural disease occurs in the pleural space, which is the thin fluid-filled area in between the two pulmonary pleurae in the human body. There are several disorders and complications that can occur within the pleural area, and the surrounding tissues in the lung.

Tracheobronchial injury is damage to the tracheobronchial tree. It can result from blunt or penetrating trauma to the neck or chest, inhalation of harmful fumes or smoke, or aspiration of liquids or objects.

Norman Rupert Barrett CBE FRSA was an Australian-born British thoracic surgeon who is widely yet mistakenly remembered for describing what became known as Barrett's oesophagus.

The pulmonary pleurae are the two opposing layers of serous membrane overlying the lungs, mediastinum and the inside surfaces of the surrounding chest walls.